Health & Medicine

Mapping how schizophrenia changes brains

Although digital technology has been blamed for some negative impacts on our mental health, new tech could provide us with future tools for treatment

Published 4 December 2017

Smartphones, social media, big data and machine learning are changing nearly every facet of our lives – and mental health services are no different.

Whether it is flagging people in psychological distress using passive sensing technology on mobile phones, or creating social media that boosts, rather than damages, our wellbeing - the potential for technology to tackle mental health is huge.

Here are four ways digital technology and artificial intelligence are being used for mental health.

Passive sensing is a promising and exciting application that mobile phones could have on our psychology.

The idea is that by analysing interactions and patterns in a person’s mobile phone usage, we can determine certain psychological characteristics and conditions.

For example, a significant reduction in outside movement tracked by your phone’s Global Positioning System (GPS) and accelerometer, possibly combined with significant alteration in sleep patterns tracked by time of smartphone usage, could indicate depression symptoms.

Health & Medicine

Mapping how schizophrenia changes brains

Digital phenotyping is a new term which means constructing a person’s real-time psychological state and overall profile based on their interactions with their smartphone. Already mental health professionals are flagging that this approach could offer “largely untapped potential for the early detection of various conditions”.

Although the system is still very much in a developmental stage and work is only just starting on working out how this data could be integrated into traditional electronic medical records - it’s an idea could offer interesting insights in the future.

Analysing the language people use can also offer valuable insights into their psychological wellbeing.

Using modern computational and Artificial Intelligence (AI) resources, we can learn how someone is feeling based on what they have written online or in a message. This means looking at information like the sentiment of the text - was it positive, negative or neutral? But also the measure of the emotion conveyed like anger, sadness or joy.

With the collections of user-post content now available from sites like Twitter and Facebook, recent research suggests that computational linguistics can identify the onset or presence of mental health conditions.

Recently, a collaboration between IBM and Columbia University have made some preliminary findings that psychosis can be predicted based on quantifiable deterioration of semantic coherence. In other research, linguistic analyses for other mental health conditions, like depression and bipolar disorder have also been developed.

Techniques like these could offer a powerful way to intercept and treat mental health conditions before they occur, or worsen.

Sciences & Technology

Three ways we’re ‘making friends’ with robots

A chatbot is a computer program that mimics conversation with users via a chat interface.

The technology is currently a hot topic in the tech and e-commerce world, but in fact, the history of chatbots is intimately tied with psychology. The first chatbot ELIZA was programmed in 1966 to simulate a Rogerian psychotherapist.

Human language is complex and we haven’t reached the point of truly simulating human conversation, let alone a replicant psychologist. While not sophisticated, they can act as conversational search assistants to help users find online therapy content and perform psychometric testing to learn from user responses in real time.

More sophisticated chatbots such as Woebot and Tess can hold basic conversations with people and, despite the limitations, a chatbot conversational mode can create a sense of connectivity and personalisation. This can offer a uniquely effective way to collect input from users.

Research on the psychology of chatbots suggests that users may be more open and likely to share information, particularly on sensitive topics, when interacting with a nonjudgmental machine interface.

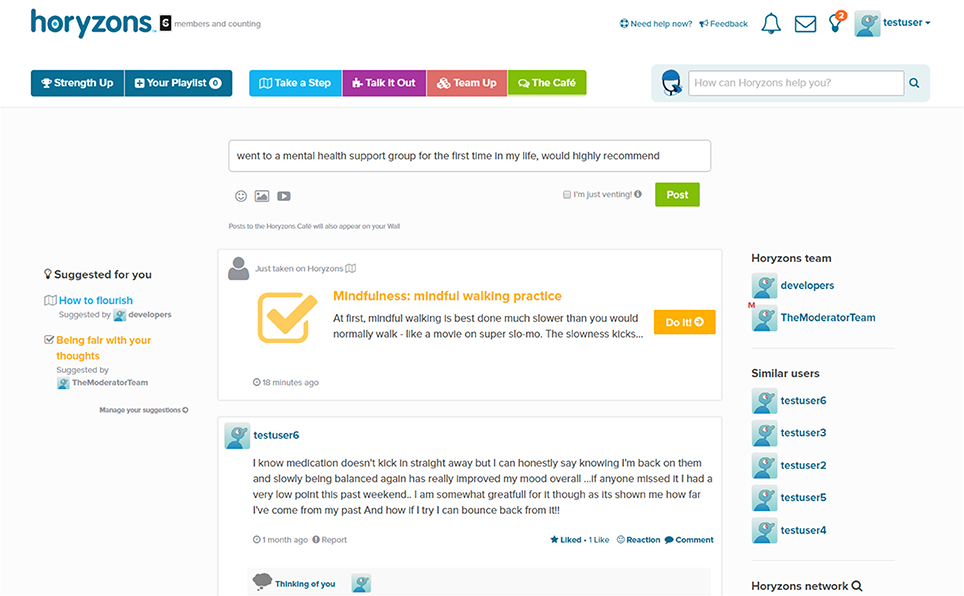

The MOST (Moderated Online Social Therapy) web platform from eOrygen combines Facebook-style social networking with specialised therapy components and a forum-like feature where users can crowd-source solutions to common problems.

The platform is flexible, and forms the backbone of tailored sites for a variety of mental health cohorts. To date MOST has been effectively trialled or will soon be trialled for a range of conditions, including psychosis, depression and social anxiety.

As with other social media and content platforms, underlying algorithms play a key role.

In common with sites like Netflix and Amazon, MOST offers tailored content suggestions, delivering timely and relevant therapy modules based on information like usage history and text analysis. Future possibilities include the integration of passive sensing.

Health & Medicine

(Don’t) always look on the bright side of life

Social media is a double-edged sword and popular sites like Facebook can be detrimental to mental health and cause or exacerbate certain conditions. Motivated primarily by commercial or advertising interests, they are designed to maximise usage time, without due regard for the user’s wellbeing.

The MOST platform avoids some of these pitfalls, instead concentrating on delivering psychologically beneficial experiences. We align ourselves with a recent movement that has emerged to counter this “brain hacking” and promote the development of ethical and useful, not addictive, technology.

So while there might be some criticism out there about the impact of digital technology on our emotional wellbeing, it’s only a matter of time before it provides us with new and effective tools to help our mental health.

eOrygen is the new interdisciplinary e-mental health branch within Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, in partnership with the School of Computing and Information Systems and the Centre for Youth Mental Health at the University of Melbourne and the School of Psychology at the Australian Catholic University.

Banner: Getty Images