Health & Medicine

The importance of your child’s middle years

Brain imaging is helping us understand why some teenage risk-taking may be beneficial during this important stage of human development

Published 19 September 2024

From movies to TV and parental anecdotes, teenagers are often characterised as risk-taking and impulsive with poor decision-making skills.

In most of popular depictions, these qualities of teen behaviour are considered problematic – both for the teen themselves and those around them.

But these stereotypes aren’t the full story.

In fact, teen behaviours – like good risk-taking – can help achieve key goals during this developmental period.

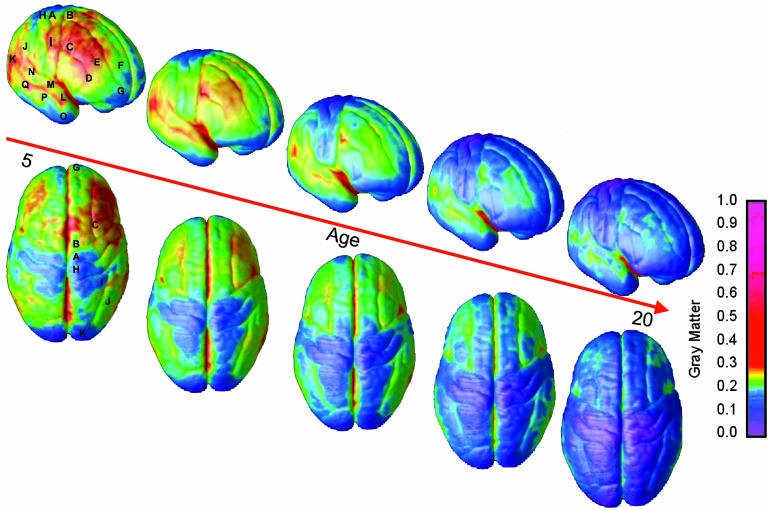

Advances in functional neuroimaging – which looks at the live human brain with magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to identify how it functions in different circumstances – provide an insight into the developing brain and decision-making during the teen years.

First, it is important to define the ‘teenage’ years.

The teen period (also known as adolescence) starts with puberty and ends when the brain’s prefrontal cortex reaches maturity – and bear in mind, it does not fully mature until the age of 25.

The prefrontal cortex is a highly specialised region of the brain, involved in higher-order cognitive functions like planning, decision-making, impulse control, emotion regulation and moderating social behaviour.

Health & Medicine

The importance of your child’s middle years

Until our mid-20s, the ongoing development in the prefrontal cortex means that the adolescent years are characterised by neural pruning (getting rid of brain synapses that aren’t frequently used) and making neural connections more specialised and efficient.

As teens age, the organisation of their neural systems becomes increasingly stable, which results in a corresponding stability in their behaviour.

Because the prefrontal cortex helps us control our behaviour and emotions, before its development is complete, teens are swayed by other neural systems that mature earlier – like the amygdala and striatum.

These structures reside deep in the middle of the brain and are responsible for emotion and sensory processing, as well as motivating us to seek out rewards.

The rewards teens seek vary, but are often social in nature; social acceptance in particular is a core motivator of adolescent decision-making.

A teen's seeming obsession with social acceptance is normal for this stage of development and allows them to figure out which behaviours are most likely to result in social status.

In fact, our recent work argues social status is actually key to the survival of human and primates, allowing individuals to access resources that benefit both their immediate and future selves.

In line with this survival benefit, teens are more prone to reward-seeking – but only in some circumstances.

For example, seminal neuroscience studies show teens make more risky decisions when they are in the presence of their peers or their emotions are heightened.

Health & Medicine

The young people getting nature on prescription

Although risk and impulsivity are often associated with negative behaviours, reward-seeking is crucial to learning how to function in daily life.

Rewards help motivate us to engage with the world around us, learn new skills and tackle challenges.

Reward-seeking often encourages risk-taking.

Even though the adolescent brain is designed to engage in risky behaviour, teens are not just driven toward risks that compromise their health and wellbeing (unsafe driving, drug experimentation, unprotected sex, to name a few).

The adolescent brain also motivates behaviours with positive goals, but these are considered risky because the outcomes are unknown and there's a potential for negative outcomes.

Some great examples include prosociality (like helping out a struggling classmate), advocacy (developing an interest in social causes), achievement (in academics, sports or employment) and social expansion (meeting new people).

Tolerance, and even a desire for, risk are necessary for developing a sense of identity, establishing autonomy from parents, honing skills and seizing new opportunities.

Parents can do a few things to redirect a teenager's urge for reward into more positive exploration.

The first step is to help your teen plan for different risky situations before they are around friends and those subcortical regions of the brain overpower their impulse control.

Health & Medicine

Good sleep is key to pre-teen mental health

For example, talk about different scenarios and let your teen reason through the ways they might respond.

What happens if they show up to a party and there's alcohol there? How will they say no to peer pressure?

Strategising before teens act will help them make better decisions, giving them autonomy with fewer negative consequences.

Parents can also let teens be a part of the rule-making process. They need to learn how to weigh rewards and costs when thinking about the future.

Encourage your teen to express their natural risk-taking desires.

Talk through consequences they want to avoid as well as other positive ways they can get that feeling of independence and reward – like taking up a new hobby or part-time job.

It may seem unrelated, but a major contributor to healthy decision-making is sleep.

And sleep goes through a lot of changes during the adolescent years.

After puberty, there's a shift in our circadian rhythms which leads to a preference for staying up later at night and sleeping in later in the morning.

This the result of changes in our production of melatonin, the hormone that regulates sleep, which tends to be released later in the evening for teens.

Teenagers also need for more sleep than they did in childhood. But, counterproductively, they often get less because of social, academic, and extracurricular pressures.

There are a lot of ways that poor sleep during adolescence can exacerbate brain development and behaviour during this time.

Arts & Culture

Ancient teens were full of existential angst too

A lack of sleep intensifies the activity of subcortical regions, like the amygdala and striatum, and impairs the prefrontal cortex’s ability to regulate impulses and emotions.

When it comes to impulse control in emotional contexts, teens who had had a poor night's sleep made the same decisions as their peers when they were doing a task that was long, boring or difficult.

But, these two groups made different decisions when the task was rewarding and emotionally arousing.

This suggests that sleep can contribute to impulsive decision-making in contexts where teen decisions are already compromised, for example, in the presence of peers.

There are several ways parents can help teens get a better night's sleep to help improve their decision-making.

Our research shows that monitoring a teen’s bedtime, getting a comfortable pillow and reducing screen time before bed can help parents improve sleep.

Although challenging, the teenage years are very special.

Understanding and embracing the opportunity will help teens reach adulthood in a safer, more competent way.

For more science-based tips on talking to teens about risky behaviours and challenges in their formative years, listen to the PsychTalks podcast.