Thermal drones are helping to monitor some of Australia’s most elusive wildlife

Thermal camera-equipped drones are revolutionising wildlife surveys in Victoria’s native forests

Published 15 September 2025

Australia’s wildlife is extraordinary but spotting a rare, nocturnal, tree-dwelling species like the Leadbeater’s Possum is hard.

And when your job is surveying endangered species, this is a problem.

Monitoring our endangered wildlife is crucial to their survival, particularly as populations shrink due to habitat loss, forest fires and climate change.

Conservation and management decisions depend on accurate data about where these animals live and how abundant they are – so to get a better picture of what’s out there, we’re swapping torches and binoculars for drones and thermal-imaging cameras.

Our new study, published in Ecological Applications, shows that drones equipped with thermal cameras can help us detect and monitor some of Australia’s most elusive forest wildlife.

Spotlight on our endangered animals

Eucalypt forests across Victoria are home to iconic animals, like koalas and platypuses.

They’re easy enough to find if you know where to look.

But these forests also shelter some of our most threatened nocturnal wildlife that only a few people would have seen in the wild.

These are animals like Victoria’s critically endangered faunal emblem, the Leadbeater’s Possum and the endangered Southern Greater Glider.

These species spend most of their time high in the trees, making them incredibly difficult to detect from the ground.

Traditional surveying is done at night using ‘spotlighting’.

We walk through the forest, sweeping torches to catch the eyeshine of animals as it reflects back to us.

Eyeshine varies by species – Greater Gliders glow golden, Krefft’s Gliders shine blue and Brushtail Possums are red – and binoculars help if identification isn’t clear.

But spotlighting can be slow and labour-intensive.

To try and estimate population numbers accurately, we often need to cover the same long transects (straight lines) repeatedly over multiple nights with multiple observers.

Even then, we may only cover a small fraction of a forest, often failing to detect all the animals present.

It’s tiring and potentially dangerous for the survey teams, especially in steep or dense forests.

Remote sensing is changing the game

New technologies are vastly improving wildlife monitoring.

Acoustic recorders can survey birds and frogs. Motion-activated cameras can detect shy mammals, which recently led to the discovery of critically endangered Leadbeater’s Possums in New South Wales, far outside their assumed range.

But animals like the Greater Glider rarely call, and their strict diet of eucalypt leaves means they aren't attracted to baited camera traps.

So for older tools like these, they're basically invisible.

This is where drones equipped with thermal cameras come in.

Until recently, most thermal drone surveys had been tested on animals like feral goats in open landscapes or koalas in tree plantations.

No one had studied their effectiveness in detecting animals at night in native forests.

With support from the Victorian Government, we flew drones across forest areas up to 200 hectares in size. We did ground-based surveys at the same time in order to compare the results.

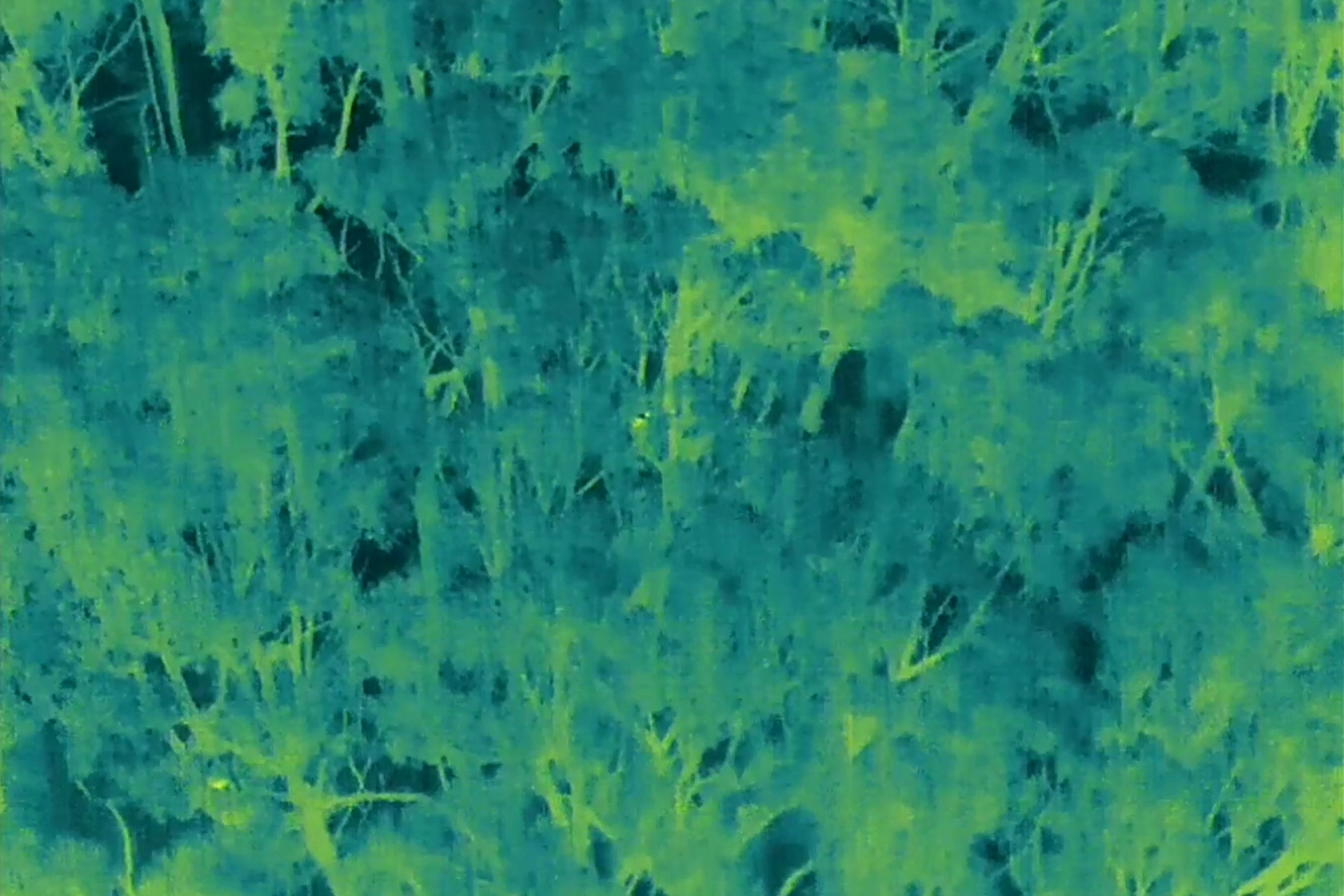

The drones flew systematic ‘lawnmower’ paths over the canopy, using thermal cameras to detect animals’ heat signatures.

Once spotted, we used a zoom camera and floodlight to identify the species.

We found that just one drone survey could cover roughly ten times the area a spotlighting team could survey from the ground in the same amount of time.

And the results were striking.

Our drones detected all nine of the arboreal (tree-dwelling) mammals we expected to see in the study area.

This included species commonly seen using spotlighting, but also animals usually detected using remote cameras like Leadbeater’s Possums, or through their calls, like the Yellow-Bellied Glider.

In total, we made more than 1000 observations of native mammals, as well as forest birds and ground-dwelling animals like bandicoots, wombats, feral deer and cats.

Our study also showed us the limitations of traditional spotlighting.

On the one hand, small, scattered populations of species like the Greater Glider are easily missed during ground surveys.

And on the other hand, when spotlighting happens in a good habitat with lots of easy-to-spot gliders, it can lead to the assumption that surrounding forests are equally as rich in wildlife.

But a change in tree species, structure or the dominance of a more general animal species like Brushtail Possums can mean there are fewer or no gliders in un-surveyed areas, meaning that population densities are overestimated.

The drone surveys were much more likely to spot hard-to-find species – giving us a richer picture of the populations over the entire habitat.

Using modern tech, we now can map animals across entire forests and see what species can co-occur, where rare animals hide and whether disturbed forests can support recovering populations.

Adding drones to the toolkit

Once we knew that thermal drone surveys were effective in finding forest-dwelling species, we conducted more than 100 additional drone surveys and found over 4000 animals, including more than 400 Greater Gliders.

Our ongoing study which draws on the benefits of drone surveys to explore the recovery of the Greater Glider from bushfires and timber harvesting in Victoria allows us to explore questions like:

Do these animals forage in younger forests?

How far from the disturbed edges do they live?

How old does the forest need to be for it to be useful for them or help to re-establish stable populations?

Getting answers to these questions can help guide future forest management.

This includes where and how to conduct prescribed burning, where to establish fire breaks and how to buffer key habitat from future disturbance to ensure that Australian species like the Greater Glider are protected.

While drones won't entirely replace all ground-based surveys, they are vastly improving the scale and detail of our wildlife observations.

Although we are watching them, most animals don’t seem to notice they are being observed from the air. But we are currently investigating the potential impacts of these new methods on animal behaviour.

Thermal drone surveys help us conduct rapid, comprehensive counts to make smarter, evidence-based decisions for the conservation of Australia’s amazing wildlife.