Why climate change adaptation is a key piece of our climate risk puzzle

Climate adaptation can make the difference between the potential impacts outlined in Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment and a more hopeful reality

Published 30 September 2025

Many Australians will have been reading up recently on whether they are likely to be among the 1.5 million reported to be at risk of sea level rise or the 190 per cent increase in heat-related deaths in Sydney.

These figures were part of Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment (NCRA), a big announcement from our Federal Government who have spoken little about climate change since the election in May.

You couldn’t be blamed if, among these alarming media headlines, you missed the quiet companion to the risk assessment: Australia’s inaugural National Adaptation Plan.

This plan outlines what the federal government is going to do to try to reduce climate risks (besides reducing emissions). Climate change adaptation is an important partner to the National Climate Risk Assessment.

Here, we’ll unpack what we mean by climate change adaptation. And why it gives Australians some much-needed hope that we can significantly reduce climate impacts.

What do we mean by climate adaptation?

Adaptation is a term that is not commonly understood and is often forgotten in climate change reporting.

Yet humans act to reduce climate risks all the time.

First Nations communities, for example, have a demonstrated history of working with their natural environments to adjust to changes in climate, using practices like cultural fire management.

We can continue to learn from these practices as we seek to innovate and improve our responses to climate change.

For this reason, when we teach or write about climate change we always begin by acknowledging a few foundational facts that are worth remembering when thinking about climate risks.

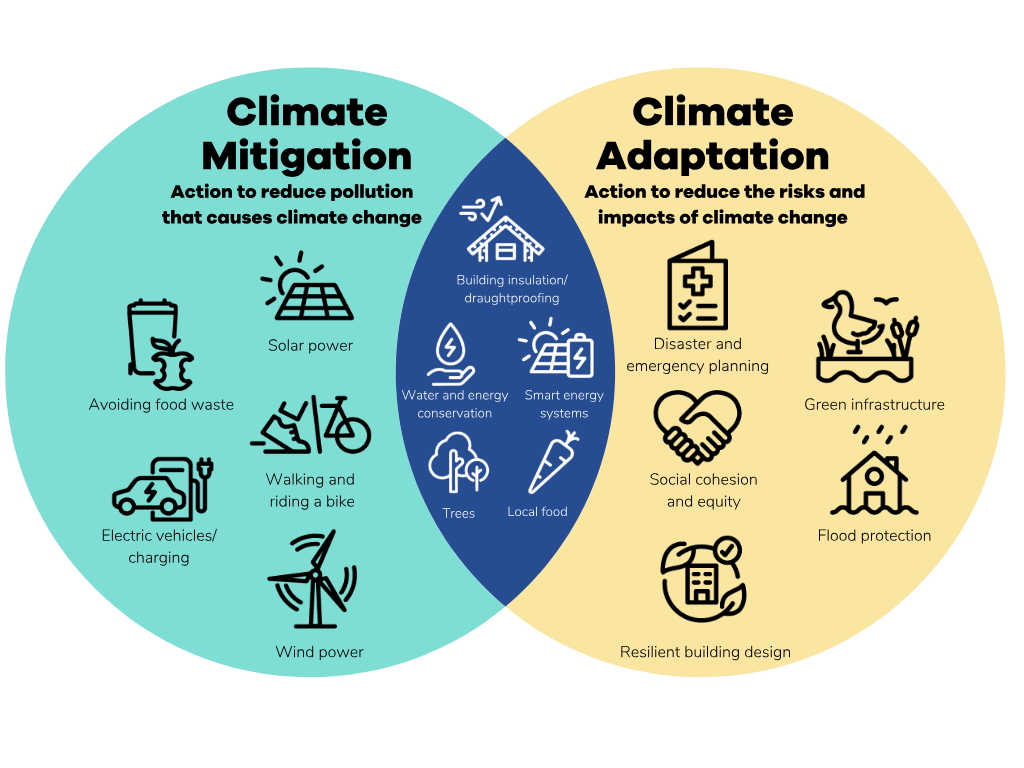

First, mitigation and adaptation go hand in hand

Climate change mitigation, in the form of greenhouse gas reduction, is going to be essential to ensure we stop exacerbating damage to our climate and natural environment.

Setting suitable net-zero targets and adhering to them is the only way we can address this persistent issue, making them a crucial point in this discussion.

For some time, however, scientists have discussed the slow uptake of climate action and limited investment from key global players to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – meaning that changes in our climate are now unavoidable.

The NCRA report demonstrates that our climate has already changed and will continue to change, regardless of whether we successfully reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

But the negative impacts of those changes depend on what we do next.

Second, adaptation can be used to reduce climate risk

It’s important to note that ‘climate change mitigation’ refers to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions to reduce human-induced (anthropogenic) climate change.

Whereas ‘climate risk mitigation’ is the practice of adjusting to actual or expected changes to reduce harm, and can be equated to ‘climate change adaptation’.

This is a key point of confusion in climate change language and an important distinction to make.

When we discuss what ‘climate risk’ actually means, we need to consider three primary factors: a climate hazard, exposure of people or assets to that hazard, and the likelihood that they will be negatively impacted.

For a climate risk to exist, these three must occur at the same time and in the same place.

And so, the climate risks reported in the National Climate Risk Assessment are not just contingent on projected future climate but also on the adaptation taken to reduce exposure and vulnerability of people and assets to climate change.

The risks outlined are based on the current situation, and if we do nothing more to reduce them.

But adaptation is a choice and a necessary pathway for Australian households and businesses.

The National Adaptation Plan was released alongside our National Climate Risk Assessment in recognition that adaptation is an important piece of the puzzle.

It outlines what the federal government sees as its role and responsibility to be, and how it intends to address each of the emerging climate risks discussed in the risk assessment.

Third, adaptation is all around – here’s what it looks like

Adaptation is not a great unknown – it's something that has been done for some time and will continue for years to come.

In response to rising concerns for heat-related deaths in cities like Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide, practitioners have been working hard to increase urban greening, which can significantly reduce the impacts of heat on local urban environments.

Trees and greenery help create shade and have cooling effects, which are particularly necessary in concrete environments that otherwise reflect heat.

Research is also underway exploring how to protect workers who spend time in the heat, finding and mapping activities that are more suitable during the hottest part of the day.

For sea level rise, local governments have already been addressing erosion issues with artificial reef instalments and beach nourishment projects where sand is used to protect from waves.

Likely, some low-lying areas will eventually be left with little choice but to relocate.

This is why extensive community consultation and collaborative adaptation planning will be necessary to find suitable solutions.

The impact of compounding, cascading and concurrent climate risks is another term we are hearing a lot lately.

Australians know best that climate hazards don’t discriminate and often coincide at the same time, on top of existing social or economic challenges (like our cost of living crisis), worsening impacts and making it more difficult to respond or cope.

In New South Wales, the state government is seeking to address this very real challenge by bringing climate change adaptation together with disaster preparation in its new Disaster Adaptation Planning approach.

While this is an area where more research is needed, we know that addressing underlying vulnerabilities in communities increases resilience to disasters and improves people’s ability to cope.

All these examples and more are captured in the Australian Adaptation Database, which has been used to inform the National Climate Risk Assessment and National Adaptation Plan about what adaptation in Australia looks like and where we need to do more work.

It is important for Australians to be aware of the ‘dire’ impacts of climate change that might be in our future, and of the need to drastically reduce our greenhouse gas emissions.

But it is also important for Australians to understand and care about what climate change adaptation is, why it is worthy of our investment and how it can create hope for our future.