A Big Build or a big bet?

Melbourne’s Suburban Rail Loop aims to help the city become more equitable – but better integration of land use and transport could deliver more benefits for less money

Published 14 June 2024

Melbourne’s current long-term strategic land use plan, defined in Plan Melbourne 2017-2050, is grounded on two core ideas.

These are that Melbourne becomes a polycentric city based on a series of activity clusters, mainly in the middle suburbs (called National Employment and Innovation Clusters – or NEICs) and Melbourne would be organised into a collection of 20-minute neighbourhoods.

The NEICs are intended to promote productivity growth through agglomeration and to develop a more equitable city – particularly by increasing employment opportunities closer to the city’s outer urban growth corridors.

The idea of improving public transport access to middle urban activity clusters has appeal, as a way of supporting their growth potential.

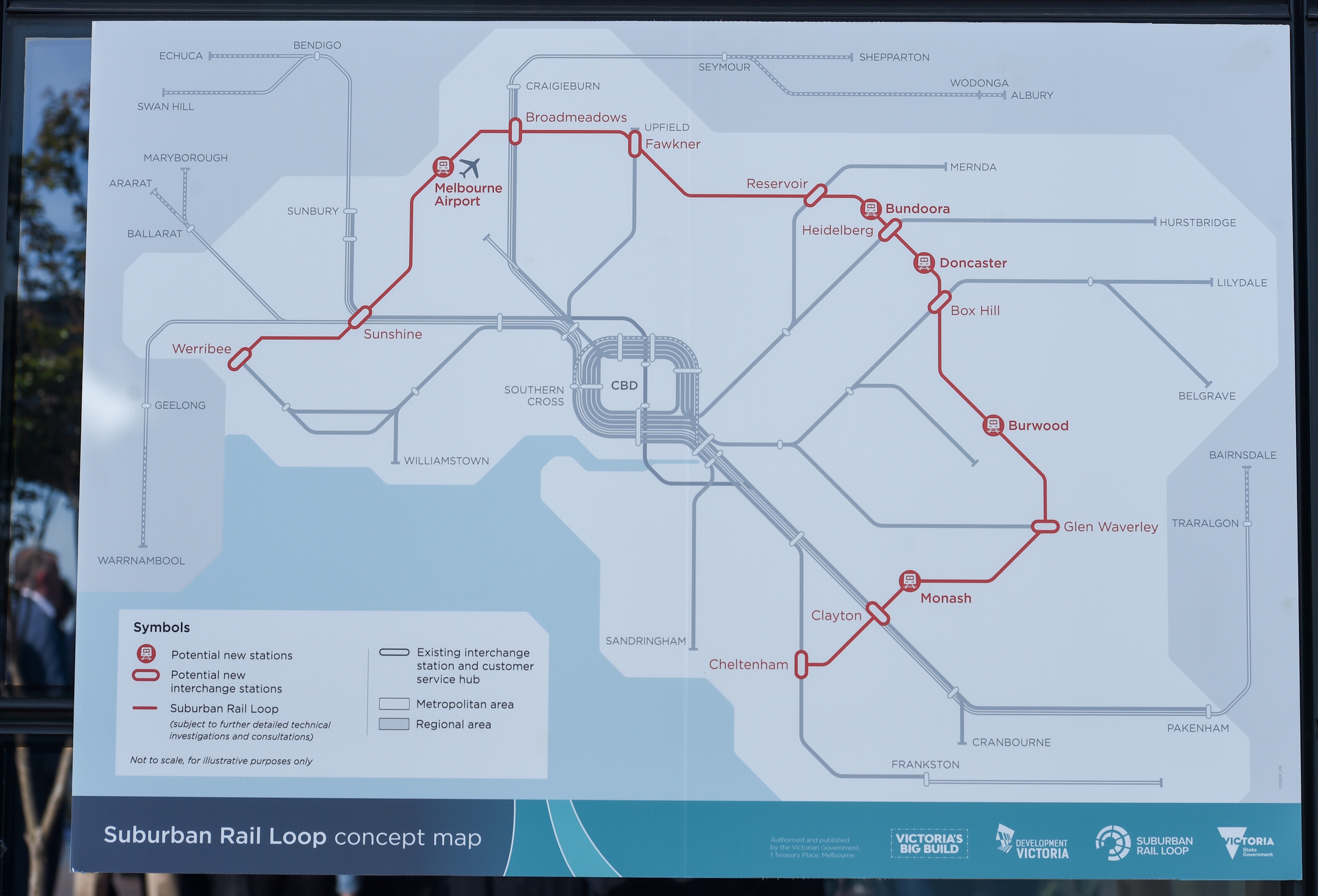

And the Victorian Government’s Suburban Rail Loop (SRL), part of its Big Build program, is intended to play this role.

But this solution is arguably too big for purpose.

Highly developed global cities that have circumferential rail services – that is, trains travelling around an urban area rather than radially to its centre – typically have densities much higher than Melbourne and their circular rail loops are quite short.

Most are also located in the higher-density inner parts of those cities where demand is strongest, whereas circumferential public transport further out typically requires transfers between services.

In 2022, Melbourne’s built-up land area has a population density of 1,746 persons per square kilometre and the SRL has a proposed length of 90 kilometres, from Cheltenham to Werribee.

Compare this to London, which data tells us has a population density of 6,504 persons per square kilometre – the city’s Circle Line is 27 kilometres long. Tokyo-Yokohama has a density of 4,584 people per square kilometre, with its Yamanote Line at 34.5 kilometres, and Berlin has 2,934 persons per square kilometre and the 37.5km long Ringbahn.

In short, Melbourne’s SRL is around three times the length of these circle lines, in a city with a much lower population density and a lower patronage potential.

Health & Medicine

Australian cities failing on walkability

The economics are against the SRL working.

The August 2021 SRL Business and Investment Case for the Cheltenham to Melbourne Airport segment of the SRL (SRL East plus SRL North) showed a positive result, with projected a benefit-cost ratio between 1.0 and 1.7.

However, there are two serious problems with this result.

First, the benefit-cost analysis was undertaken with a low discount rate (four per cent) to convert future benefits and costs over the project’s lifetime into present-day values (this is needed to derive benefit-cost ratios). The usual Australian discount rate for evaluating major infrastructure projects – seven per cent – would have delivered much lower returns for the SRL.

A good argument can be made for using a four per cent discount rate for a project with a long life span, like the SRL, but this is not the usual public policy approach in Australia (unlike in the UK).

The choice of this discount rate should be subject to wide debate, including consideration of implications for the evaluation of alternative investment opportunities whose impacts accrue over shorter time frames.

Second, as well documented in the media, the expected cost of the project has increased substantially. The cost was estimated at around $AU50 billion for the full project at the initial announcement in 2018, rising to $AU35-57 billion for SRL East plus North in the Business and Investment Case.

The figure now stands at $AU125 billion again for SRL East plus North, as estimated by the Victorian Parliamentary Budget Office.

Politics & Society

The making and unmaking of the East-West Link

This would take the capital cost for the full SRL to around $AU200 billion, or about four times the initial estimate made only a few years ago.

Unfortunately, the expected benefits do not grow anywhere near as quickly as this rate of cost inflation. If evaluated today with a more usual discount rate, the SRL would struggle to generate even 50 Australian cents of benefit per dollar of capital cost.

This should be a cause for concern.

Medium capacity transit (MCT) solutions, as proposed by the Rail Futures Institute, are likely to be a more cost-effective and flexible solution to meeting the circumferential public transport accessibility needs of Melbourne’s middle urban clusters in a faster timeframe.

This kind of cluster development could then be further enhanced by direct investment in cluster competitive strengths – like supporting further growth of their universities and hospitals or medical research facilities – together with investing in place-making.

These investments plus MCT would be a more integrated way of promoting polycentric growth in Melbourne than relying so much on the SRL.

The savings from not pursuing the costly development of the SRL could also be used to promote a much faster roll-out of the distinctive and very innovative Plan Melbourne idea of 20-minute neighbourhoods; this concept has been taken up by many European cities as well as others in Asia, Canada, South America and recently, Singapore.

Environment

New fixes for old traffic problems

A 20-minute neighbourhood offers most services that most people need most of the time, including shops, schools, health services, parks and recreation.

This form of land use reduces urban sprawl through higher-density housing, builds community and fosters social capital, improves accessibility and offers a greener environment.

As a result, the likely outcomes are improved health and wellbeing, increased social inclusion and increased economic productivity, along with a reduced need to travel, which also helps to reduce transport emissions.

The Victorian Government is trialling 20-minute neighbourhoods in Melbourne. However, these trials have overlooked the public transport component, instead relying on walking and cycling.

An 800-metre catchment, as used in the trials, and said to be an acceptable walking distance, is unlikely to offer access to many service needs. This dependence on active transport doesn’t offer equality in opportunity for all people, potentially leaving out many older people, those moving or carrying heavier loads, people with an impairment and people with multi-tasking requirements – like work, child-care and school drop-offs, shopping and the list goes on.

A larger neighbourhood is required to offer essential services, supported by a frequent neighbourhood local public transport service.

Improving circumferential public transport access to serve Melbourne’s middle urban clusters is an important requirement for delivering the city’s intended land use development. But the Suburban Rail Loop is an expensive solution to this challenge.

It comes at the cost of other important infrastructure and service improvements that are likely to be effective in reducing inequality and facilitating growth with lower emissions.

Medium Capacity Transit options plus direct investment in cluster development is a more cost-effective way forward, complemented by a greatly accelerated rollout of 20-minute neighbourhoods across middle and outer urban Melbourne, at increased densities.

This would give Melbourne big benefits without such a big bet.

Banner: AAP