Health & Medicine

Into the wild to fight antibiotic resistance

Two million Australians self-report an allergy to penicillin – but most actually aren’t allergic – and this can lead to serious public health consequences

Published 20 June 2023

When filling out a medical form or hospital admission document, if you’ve ever reported an allergy to penicillin, you’re not alone. But you may be mistaken.

More than 10 per cent of the Australian population self-report having a penicillin allergy. However, research shows only one per cent of people are truly allergic to the drug commonly used to treat bacterial infections, including those found in the throat or on the skin.

It’s World Allergy Week which is the perfect time to shine a light on one of Australia’s most alarming health concerns – drug allergy.

Health & Medicine

Into the wild to fight antibiotic resistance

The first question is, why do so many people think they have a penicillin allergy?

Well, it’s complicated. If you have been told you are allergic to penicillin, it’s a normal response to continue to report the allergy to protect yourself from re-exposure and any future allergic reactions.

At some point, you might have had an allergic reaction to a specific drug (like amoxicillin), but it’s now known that around 80 per cent of people who experienced an allergic reaction to penicillin more than 10 years ago, will have outgrown that allergy with time.

Maybe you have experienced a drug side effect, like an upset stomach that was inadvertently labelled as an allergic reaction in your medical record, or you were labelled as allergic to penicillin after experiencing a rash that could possibly have been the result of a childhood virus.

Allergy assessment and testing, performed by trained health professionals, is the safest approach to determining if a penicillin allergy truly still exists.

The second question is, why is the overestimation of penicillin allergy important?

Health & Medicine

A new weapon in the war against superbugs

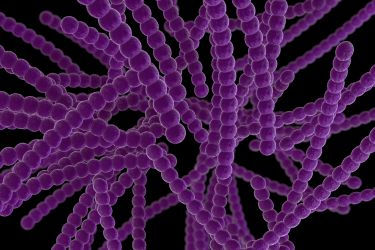

The problem is antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is on the rise.

In November 2021, the World Health Organization declared AMR as one of the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity. Antibiotic allergy labels and subsequent prescribing of inappropriate antibiotics are contributing factors.

For example, once a penicillin allergy is documented in your medical record, you are more likely to experience negative outcomes.

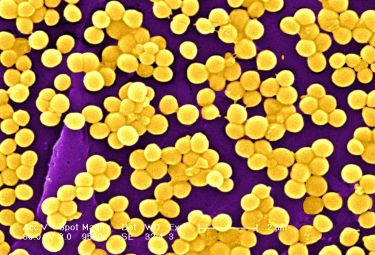

The worst-case scenario is developing an antibiotic-resistant superbug – or bacteria that causes infection that’s not treatable with the usual antibiotic regimens, including penicillin and other first-line drugs.

This can happen because patients who report a penicillin allergy are at an increased risk of inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing. This is when a patient receives less preferred or ‘second-line’ antibiotics to treat an infection – these may not work as effectively or cause adverse drug reactions, longer hospital stays and increased rates of re-admission.

To help, allergy researchers are investigating ways to remove penicillin allergies from patients’ records – this is called delabelling – and using point-of-care assessment and testing programs, like skin-testing or direct oral penicillin challenge procedures, to more accurately determine if a true allergy exists.

Following accurate history-taking and risk assessment using validated antibiotic allergy assessment tools, more than half of all penicillin allergy labels in the inpatient setting are considered ‘low-risk’. Many of these penicillin allergy labels have the potential for delabelling via testing, like a direct oral challenge procedure.

Health & Medicine

Stronger action to curb overuse of antibiotics

Concerningly though, in Australia, many of the two million people who report an antibiotic allergy label (AAL) don’t have access to this type of testing.

It’s clear, we need to change the domestic landscape of antibiotic allergy management. To help address this – and other gaps in allergy research – the National Allergy Centre of Excellence (NACE), Australia’s peak allergy research body, awarded nine Postgraduate Scholarships this year to foster the next generation of allergy researchers.

Our research team, with support from the NACE, is conducting the first global review of the evidence for multidisciplinary, low-risk penicillin allergy delabelling.

Work is also underway to evaluate inpatient penicillin allergy thanks to the launch of the National Antibiotic Allergy Network (NAAN) National Inpatient Penicillin Allergy (NIPA) database in November 2022.

In its first few months, the NIPA database has already enrolled eight Australian health services, with more Australian and international sites also poised to join the study.

The information gathered over the coming months means that for the first time, in a large cohort of Australian patients, we will be able to assess the safety and impact of health service penicillin allergy delabelling programs.

The study is being led by a range of disciplines including Allergy/Immunology and Infectious Diseases physicians, Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) pharmacists and nurses.

We are also conducting a nationwide survey to better understand clinician beliefs about penicillin allergy delabelling. This will guide future research on how we can improve access to penicillin allergy delabelling for all Australians, particularly in areas like regional and rural communities, where access to allergy and immunology services is limited.

Health & Medicine

How allergies may get under our skin

The end goal is to broaden the future drug allergy workforce to include pharmacists, who can potentially upskill to offer penicillin allergy testing, perhaps using oral challenge programs in low-risk inpatients.

Our research will provide the evidence base to develop a credentialled, Australian AMS pharmacist-led, inpatient penicillin allergy delabelling program.

Ultimately, we expect multidisciplinary approaches to penicillin allergy delabelling will help reduce the economic burden on hospitals, increase access to drug delabelling and improve antibiotic prescribing for people who suffer a broad range of infections requiring penicillin.

A collaborative approach to this health crisis is key to improving the lives of people impacted by drug allergy while also working towards the bigger picture of improved clinical practice, patient care and standardisation of antibiotic allergy management at a national level.

With rising antibiotic resistance, this will be a significant step forward in the global fight against antimicrobial resistance.

Banner: Getty Images