Health & Medicine

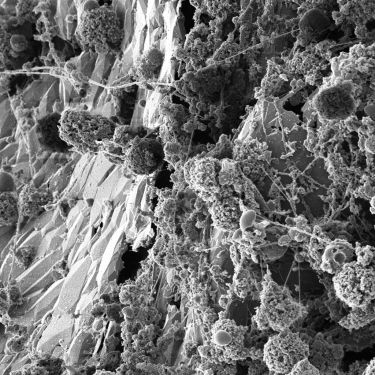

Caught! The cell behind a lung cancer

Book extract: As medicine and health care around the world undergo major changes, a new book “Stem Cell Tourism and the Political Economy of Hope” looks at the rise of people travelling in the hope of a cure

Published 11 May 2017

In Australia, in recent years, there have been a number of news reports of patients and carers travelling overseas for stem cell treatments. Their journeys are part of a wider international trend, commonly referred to as stem cell tourism, whereby patients and their carers travel across geographical borders and jurisdictions to receive treatments that are experimental or clinically unproven, and hence, may not be available to them where they live.

The stories features in the news are often framed within a now-familiar narrative—desperate patients full of hope investing in treatments that promise much, and scientists and doctors voicing frustrations about entrepreneurial ‘charlatans’ or ‘cowboys’ operating at the margins of medicine and exploiting ‘regulatory loopholes’ to sell ‘snake oil’.

Why, authorities ask, do patients and carers embark on such treatments that are unlikely to provide benefit, are expensive, and potentially in inflict great harm?

By their accounts, patients and carers tended to embark on the search for information, about the condition itself and about treatment options, very soon after diagnosis, and often in the absence of definitive expert advice.

Ivan, a father-carer of a child with cerebral palsy, articulated a commonly expressed view; namely, that ‘no one gave us any real direction so we sort of had to do all the research ourselves’.

Research can be long and tortuous, spanning in some cases a period of years, and take individuals and their families down numerous avenues, and sometimes ‘blind alleys’. Their post-diagnostic experience is thus in many respects similar to that of other patients, such as those suffering genetic conditions, long reported in the literature.

Health & Medicine

Caught! The cell behind a lung cancer

However, the rise of the internet and social media, along with the burgeoning number of online resources, has radically changed the architecture of ‘choice’. During their investigations, patients and carers encounter an array of online resources, found primarily via search engines such as Google, and information provided by disease-specific patient communities, individual patients and their families, as well as information offered by providers on their websites.

A number mentioned the importance of Facebook for sharing information, and YouTube videos and blogs for finding relevant sources. Through these avenues, and invariably after being advised of their limited options by their treating doctors after diagnosis, individuals soon came to the realisation that their options for proven treatment in Australia were limited or non-existent.

The nature of the condition and the prognosis constrain options and the potential and urgency to pursue those that are available. Individuals who embark on a stem cell treatment are in most cases struggling with severe, life-limiting conditions (e.g. spinal cord injury, motor neurone disease, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy), some terminal and, for many, time is of the essence.

As one patient, Greg, with a progress degenerative neurological disease affecting movement, explained in relation to his decision to pursue stem cell treatment in China: ‘If you’re in a condition like mine or cancer ... you will try these sorts of things. If you haven’t got a condition like that you tend to be more sceptical.’

As he reasoned, stem cell treatment ‘seemed to have more going for it’ than ‘the whole range of things out there’ and, as they were financially able to undertake treatment, ‘Well, why not try it now while I can?’.

At least in one case, an element of pragmatism played a role in the decision to undertake stem cell treatment. Parents of a child with cerebral palsy, Ivan and Vlasta, said they had explored and tried various therapies and hoped that stem cell therapy would offer something different—a ‘sort of more attractive way of try and give him a little boost’—thereby obviating the need for intensive, time- consuming daily therapy. As they explained, ‘We’re very busy people and running [a] business, and we have very little time to ourselves’. This pragmatism also appeared to be a factor in their decision to take their child for treatment in Germany and China.

In their search for options, some individuals experimented with diets and complementary and alternative therapies.

Two patients—a patient with multiple sclerosis and a mother-carer of a child with autism—mentioned that their research had uncovered the role of nutrition, which had led them to exclude gluten and dairy from their diet, which they felt had resulted in improvements in health.

In the latter case, as in a number of others, stem cell treatment was seen as additional to rather than supplanting complementary and alternative therapies—as one of an array of options that was seen as worth exploring. For some participants, clinics that were offering treatment ‘packages’, which included a range of therapies beyond Western biomedicine (i.e. acupuncture, massage, traditional Chinese medicine) in addition to stem cells, were particularly attractive and influenced their decision of where to travel.

The lack of stem cell treatment options in Australia was often cited as being crucial in the decision to travel overseas. Many individuals commented or implied that stem cell treatment should have been available to them in Australia and, since it was not, they felt that they had ‘no choice’ but to seek treatment overseas.

One carer, Donna, whose partner suffered a rare neurological condition, when asked about the benefits for people travelling overseas for stem cell treatments, responded: ‘Well you can’t get it here so you don’t really have a choice. If you want to try it ... well you don’t have a choice’.

A patient who had spinal cord injury, Axel, expressed similar sentiments when explaining the treatment challenges confronting those in his community: ‘If there’s no treatment available in Australia now and there won’t be for a long time ... we’ve got no choice but to go over- seas to get treatment in the future.’

Indeed, some described feeling ‘desperate’ about their situation, underlining the anguish that they experienced. As we explain, this sense of abandonment, loss of hope and/or desperation does not always lead to the decision to pursue treatment; however, for virtually all, this perceived hopelessness and limited options or ‘no choice’ in Australia defined the context within which decisions were made.

Banner image: In Pictures Ltd./Corbis via Getty Images

This is an edited book extract from Stem Cell Tourism and the Political Economy of Hope whichis published by Palgrave Macmillan. More information is available here.