Politics & Society

The past is never in the past

Atrocities in Bucha and elsewhere in Ukraine recall the horrific memories of the Katyn massacre and Soviet denials

Published 11 April 2022

Media reports about discoveries of bodies lying by the roadside in the Ukrainian city of Bucha have shocked the world – hands tied behind their backs, a bullet wound to their heads. Hundreds have been found dead in the wake of Russian invasion of Ukraine as the evidence of atrocities mount.

Accusations directed at Russian troops have been dismissed by Russia’s foreign minister as a “staged provocation” and “fake news”. The world has heard it all before.

The same denials were made by Moscow when the world learned about the murder in 1940 of over 20,000 Polish army officers and others by Soviet secret police – the NKVD.

The lie about their fate underpinned the whole existence of the so-called Polish Peoples’ Republic, the Soviet-sponsored puppet regime established in Poland after 1944.

Politics & Society

The past is never in the past

Those who were considered by Soviet strongman Joseph Stalin to be “intelligence agents and gendarmes, spies and saboteurs, former landowners, factory owners and officials” were executed in April and May 1940 by the NKVD. Among those who were murdered was the chief Rabbi of the Polish Army, Baruch Steinberg, as well as officers of various ethnic origins that made up Poland before 1939 – Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Jews.

The victims of these atrocities were among some 250,000 Polish prisoners of war held by the Soviets as the result of the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939. Soviet Russia had invaded in alliance with Nazi Germany according to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, a non-aggression pact between the two totalitarian regimes signed on 23 August 1939.

Initially, Polish prisoners were detained in a network of POW camps. Some of the rank-and-file prisoners were released in October 1939 but the officers were seen as anti-communist adversaries of the USSR. The Soviet Government decided to hold army officers together with police officers in camps in Starobielsk, Kozielsk and Ostashkov.

Among those imprisoned was a large number of those who served in the army reserve and were only mobilised on 1 September 1939 in the wake of the German invasion of Poland. Most of these non-commissioned officers were doctors, lawyers, teachers and academics as well as public servants and priests.

They were considered enemies both in political and ideological terms as they represented a degree-educated professional group of community leaders.

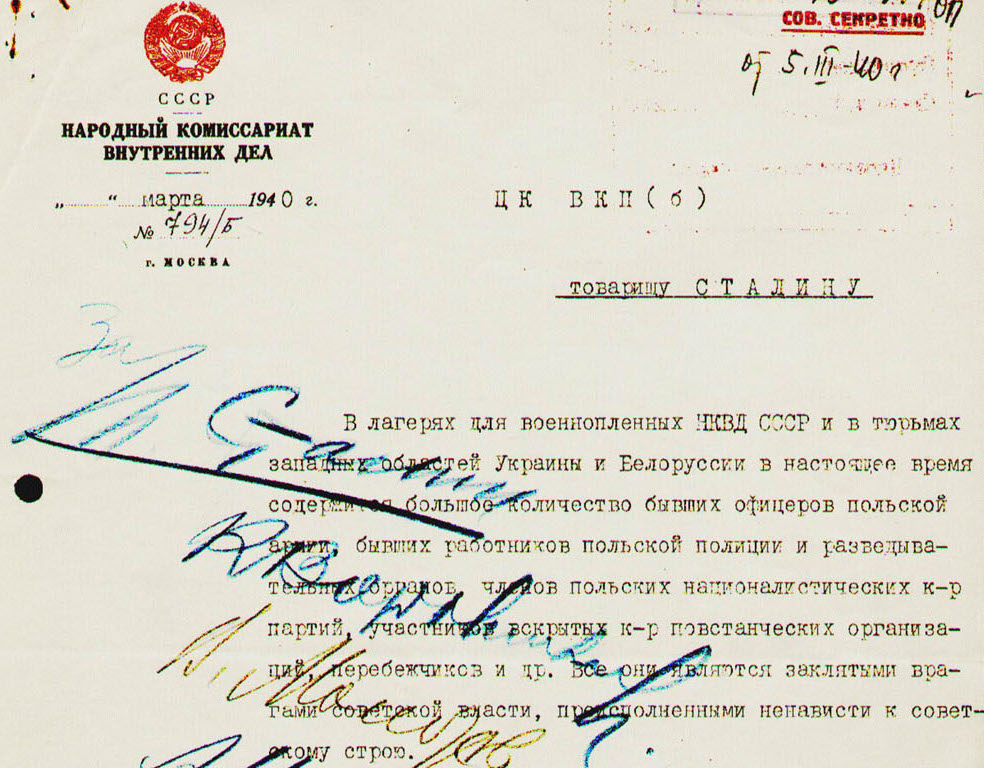

The decision to murder the prisoners was taken by the leadership of the Soviet Union on 5 March 1940. Lavrentiy Beria, Stalin’s secret police chief, in his memo addressed to the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union argued that the Polish prisoners represented “unpromising enemies of Soviet authorities” and as such should face the death penalty. The acceptance of this decision was confirmed by the signatures of Stalin, Defense Commissar Kliment Voroshilov, foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and others.

Politics & Society

Stepping carefully amid conflict in the Pacific

The murders commenced in April 1940 with the decision to close the camps in Starobielsk, Kozielsk and Ostashkov. During the next six weeks, the prisoners were taken from the camps to the places of their execution.

The scale of this murder is staggering. From Kozielsk, over four thousand people were transported to Katyn forest, near Smolensk in Russia, and murdered by shots to the back of the head. The massacre site was later found by the invading Germans, who uncovered bodies that had their hands tied behind their backs.

Another group of the same size from Starobielsk were killed at the NKVD’s prison in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Over six thousand army personnel from Ostashkov were murdered by the NKVD in Kalinin (now Tver), near Moscow.

During the same months, other Polish prisoners in various locations in Belarus and Ukraine were executed. The number of casualties was in the thousands.

In parallel, the Soviets deported the families of the prisoners of war deep into the USSR. Over 60,000 people were deported, mainly to Kazakhstan.

In April 1943 with the German advance into the USSR, the discovery of the mass graves in Katyn was made public. Hitler’s propagandist Joseph Goebbels attempted to use the event to split the unity of the Allies while the Soviets blamed the murder on the Germans calling it “the most villain and despicable lie”.

Politics & Society

Southeast Asia matters to Australia

Moscow reacted to the demands by the Polish Government in London for an explanation, by branding them “Hitler’s Polish helpers”. Within a month Moscow broke its diplomatic relations with the Poles, opening the way to establishing a puppet Polish Government.

The Allies, concentrating on the defeat of Germany, maintained a strict diplomatic silence. But after the war in 1945, when the Soviets attempted to include responsibility for the Katyn massacre in the indictment of the Nazi leadership during the Nuremberg trials, their request was denied.

In their investigation of the atrocities Russia has now committed in Ukraine, the international community this time mustn’t remain silent.

Banner: Getty Images