Health & Medicine

How brain rhythms can reveal your personality

New research on brain activity suggests that we can prepare ourselves for those situations in which we know we’ll need to control our emotions

Published 29 July 2020

In our everyday life, we experience a wide range of emotional situations. In these situations, we often want to regulate our feelings.

For example, when watching a scary movie, we may not want to get too scared – it is just a movie after all. We can do this in different ways, using different emotion regulation strategies. You might try a distraction strategy and think about something else, like what you are going to eat for dinner.

Alternatively, you could use a reappraisal strategy, which involves reinterpreting the meaning of what you are experiencing – you could remind yourself that the movie isn’t real, and that the characters are actors.

Sometimes, you may also be aware that an emotionally charged situation is coming up.

Keeping with our movie example, if you had the opportunity to prepare for a scary scene that you think is about to happen, would this period just before the scary scene help you to regulate your emotions more effectively and stop you from jumping up and startling the cat?

Health & Medicine

How brain rhythms can reveal your personality

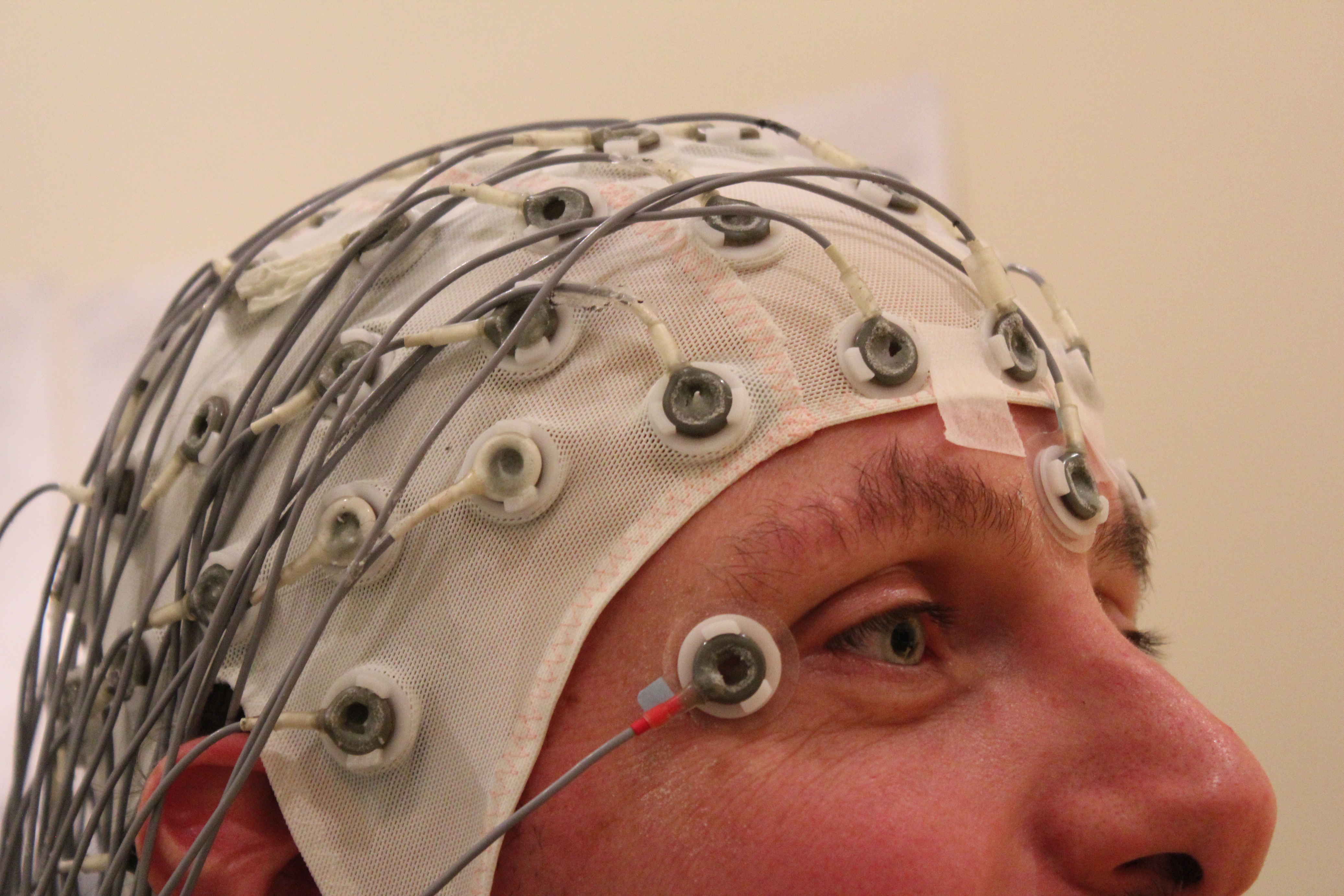

We addressed this question in our latest published research using electroencephalography (EEG), a technique that records brain activity from electrodes placed on the scalp.

From these recordings, we can identify specific patterns of brain activity that are thought to reflect things like a person’s emotional response to an image.

EEG can record changes over very a short periods of time – measured in milliseconds rather than seconds – so it allows us to examine how cognitive and emotional processes quickly unfold over time.

Recently, researchers have also begun to use a technique called multivariate pattern analysis to analyse EEG data. This technique might allow us to predict a behavioural variable (like for example a person’s emotional state) from their brain activity data, including EEG, using algorithms borrowed from machine learning.

Our experiment, conducted in the Decision Neuroscience Lab at the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences, included a series of trials in which participants were cued to either passively view an upcoming image, or were instructed to use distraction or reappraisal.

An image then appeared that was intended to elicit disgust or sadness.

After viewing the image or applying an emotion regulation strategy in response, participants then rated their current level of sadness and disgust. Throughout each trial we recorded participants’ brain activity using EEG.

Health & Medicine

Unlocking the secret to changing our minds

Using multivariate pattern analysis, we trained the algorithm to look for patterns in the EEG activity that directly predicted how successful emotion regulation was on each particular trial.

In other words, we could see whether our participants’ brain activity was directly predictive for how successfully they regulated their emotions each time.

The surprising result was that when people were cued to use reappraisal, participants’ brain activity already started to be predictive of regulation success just before a negative image appeared.

This suggests that from the moment we know that something bad is coming, it is already possible to predict how well we will deal with it. This implies that mental processes are occurring while people prepare to regulate their emotions and that these are important for subsequent success.

Interestingly, this was only the case for when people used the reappraisal strategy, but not when they prepared to distract themselves.

This could be because reappraisal is more cognitively demanding – in order to reappraise, you need to firstly concentrate on the details of an emotional situation, which takes more mental effort than simply disengaging by distracting yourself.

Although reappraisal is more demanding, in some situations, it is also more effective than distraction. Therefore, our results might shed light on how we can optimise reappraisal in a real-world context to better prepare ourselves for emotionally challenging situations.

Health & Medicine

The mental marathon of COVID-19

For example, these results could be useful for informing the development of specific emotion regulation training programs or interventions.

Given our results suggest that preparatory mental processes help people to use reappraisal successfully, it may be possible to train people to optimally prepare for using reappraisal in preparation for dealing with a difficult situation that they know is coming up.

Our results are also interesting due to the novelty of the methods we used.

To our knowledge, our study was the first to use multivariate pattern analysis to predict emotion regulation success from EEG data. Based on this, it might be possible to use this technique for similar but more sophisticated applications in the future.

For example, it might be that when emotion regulation strategies are more effective, the algorithm is able to predict the success of these strategies from brain activity more accurately.

We could then look at changes in the algorithm’s performance to evaluate the effectiveness of different emotion regulation training programs or particular instructions.

Overall, our study opens up interesting possibilities for future studies by showing that machine learning techniques, when applied to neural data, can be useful tools for investigating emotion regulation processes.

Health & Medicine

Is psychiatry shrinking what we think of as normal?

Future studies might also tell us more about how preparatory processes might set you up for successfully using reappraisal to deal with emotional situations.

Going back to the movie example, our study suggests that how you use that period when the music gets eerie and you know a scary scene is coming may help determine how successfully you will be able to control your fear.

If we had you wired up to record your EEG, we could probably even tell you how well you will do – but that might just ruin the fun of watching a good scary movie.

What we now want to understand is how we may be able to optimise this ‘preparation phase’ so that when the monster suddenly appears, you can enjoy it without having to calm a rudely awoken cat.

Banner: Getty Images