Architecture and design in a post-pandemic world

The pandemic has reinforced that design and physical space plays a role in enabling disease to spread. But the built environment can also support infection control, as the past has shown

Published 18 August 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives in myriad dramatic and unprecedented ways.

We are currently learning how to navigate the world around us, keep ourselves and our loved ones safe, and carry out our day to day lives in ways that look very different from a few short months ago.

The pandemic has reinforced that design and physical space plays a role in enabling disease to spread.

covid-19 and our built environments

Fuelled by a fear of disease and the need to protect public health not seen for some years, people scrambled to bolt on new protective devices to our environments. Sneeze guards, barriers and hazard tape all now serve to choreograph our movements.

Furniture has been rearranged, screens erected and signs of visual instructions remind us what we can and cannot do.

Until we find a vaccine or cure for emerging diseases like COVID-19 we will have to look to the physical and behavioural aspects of our lives to manage the potential for epidemic spread – social distancing, quarantine, isolation, and, perhaps, adaptations to our cities, neighbourhoods, and homes as well as what we wear.

Visitors to Brunelleschi’s 295ft high Duomo in Florence now don wearable devices, which signal with a sound, vibration and light when the minimum allowed distance between people is being exceeded.

Interventions like these mean we need to consider space in our current concern with infection control. This leads us to think about – by looking back and looking forward – how can the built environment respond?

sanatoriums, sinks and science

Some of the most significant architectural experiments throughout history have come from a focus on physical space and its role in treating, curing and preventing sickness long before vaccines were available.

Hygiene was a principle that ran through the entire design process of architect Alvar Aalto’s tuberculosis sanatorium in Finland, built in 1929.

Finland had suffered the greatest loss of life to tuberculosis across the European countries and the design by Alvar and Aino Aalto is widely regarded as the first example of modern architecture applied to healthcare.

With no pharmacological treatment for tuberculosis, the Aaltos turned to the curative effects of access to light, air, and sunlight to shape their architectural response.

Along with the building, the Aaltos also designed the sanatorium’s furniture and tableware, conceiving a sort of total artwork aimed at improving people’s health and well-being in a peaceful environment.

The 1931 Paimio Sanatorium Chair Alvar designed is still produced today. The angle of the chair’s back, built from bent birch plywood and therefore easy to clean, was designed to put the seated patient in a position that optimises their breathing.

Washing one’s hands was also seen as a basic ritual of good hygiene and the Aaltos designed the angled basin as a symbol of this, to be used with as little noise as possible.

They also designed the doorhandles in a more infection resistant material, and curved them to prevent the doorhandles catching the coats of visiting doctors.

Writing in her diary of her experiences tending to wounded soldiers during the Crimean War of 1853, Florence Nightingale notes that: “quite perceptible in promoting recovery, [are] being able to see out of a window, instead of looking against a dead wall; the bright colour of flowers, the being able to read in bed by the light of a window close to the bed-head.”

As medicine advanced throughout the 20th century with antibiotics and immunisations the reliance shifted from the psychological benefits of a total environment to hospitals as systems of efficiency and hygiene control.

The model of care decoupled away from architecture and interiors, which were instead relegated to backdrops within the treatment process.

The re-emergence of the role of the physical world

We will likely leave some things behind in lock-down, but choose others to take forward with us. Lockdown has catalysed many significant changes and innovations across sectors, involving a radical rethink of how we are conducting our lives.

Environment

Identifying the ‘Paris-End’ of town

Woods Bagot’s AD-APT modular apartment fit-out with options for day, night and play mode, and the distance disco held on neighbouring balconies at The Nightingale apartments show us that people are interested in using their environments differently, and thinking about their environments differently.

A return to a total design

Not so long ago, the expression ‘Total Design’ was part of the basic vocabulary of architects, teachers, and critics. Yet it is remarkably absent from contemporary debates.

Mark Wigley in the Harvard Design Journal, suggests that, “Total design … might be called, on the one hand, ‘implosive design’, which takes over a space, subjecting every detail, every surface, to an over-arching vision and in parallel, ‘explosive design’, which considers, the expansion of design out to touch every possible point in the world.”

At a city-wide scale, unprecedented growth in Paris in the mid 1800s saw the city thrust into a period of rapid urbanisation.

Health concerns shifted from a focus on cholera to tuberculosis and a myriad other diseases present in the hastily erected migrant workers’ housing.

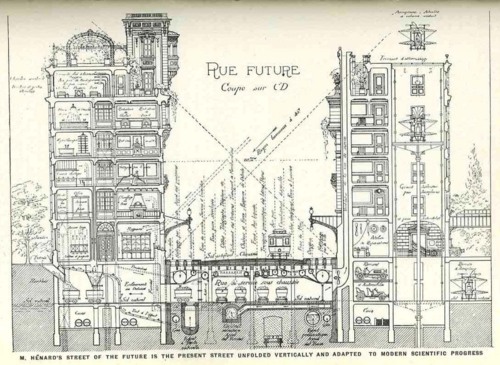

In response to this environment, Eugène Hénard proposed the ‘City of the Future’ whereby utilities, services, vehicular and pedestrian movement were separated into a hierarchy.

Also central was a focus on affordable sanitation code compliance, and housing which would better support the health of residents. This was an adaptive, flexible system which could accommodate the future needs of the city.

Perhaps this current state of disruptive innovation is ripe for a return to total design, not as a mechanism of control per se but as a holistic way to engage with the environments in which we live, move through, work and recreate on a daily basis.

Rather than making piecemeal and ad hoc adaptions like temporary sneeze guards, we need to emphasise the role of the physical space from the macro to the micro scale.

At the small scale we need to emphasise for example a focus on more infection-resistant materials for door handles, or perhaps, designing for no door handle at all? At a larger scale, beyond architecture, we will need to recalibrate how we think about trams, lifts and other related modalities after COVID-19

The air of change is upon us already, along with the opportunity and urgency to rethink our ‘Total Environment’.

Banner: Getty Images