Health & Medicine

The genomic jigsaw of cancer

The guidelines for treating early stage rectal cancer recommend immediate surgery, but research suggests some patients are having chemoradiotherapy before surgery that doesn’t benefit them

Published 23 February 2020

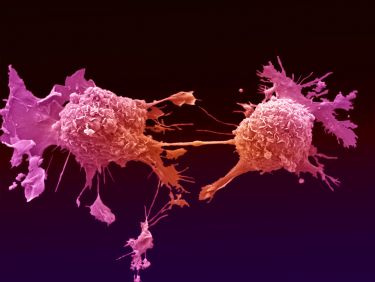

Rectal cancer is difficult to detect at an early stage because it produces fewer symptoms, like bleeding and anaemia, than more advanced rectal cancer.

As a result only about 20 per cent of rectal cancers are diagnosed at Stage 1, where the cancer has yet to spread deeper into the walls of the rectum.

When rectal cancers are caught early, they are more often than not detected in the lower part of the rectum where the recommended treatment, according to European guidelines followed by clinicians (surgeons and oncologists) here in Australia, is immediate major surgery to remove the cancer as soon as possible.

However, in our recent study we found that, contrary to international guidelines, just over half of patients with early-stage cancer of the lower rectum across seven Melbourne hospitals had also received chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy (chemoradiotherapy) prior to their surgery.

Why is this happening and does the chemoradiotherapy do any good?

When it comes to dealing with lower rectum cancer, there are good reasons why surgeons may want to recommend chemoradiotherapy before surgery.

Health & Medicine

The genomic jigsaw of cancer

Current international guidelines don’t provide a lot of detail about treatment specifically for the subgroup of cancers occurring in the lower rectum.

The lower part of the rectum has a different and more complex anatomy compared to the upper part of the rectum, and this may make surgeons more concerned about potentially missing some cancer and leaving some cancer cells behind after surgery.

So, surgeons may choose to add chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery to increase the likelihood of shrinking the tumour to ensure a clear cancer-free margin after surgery.

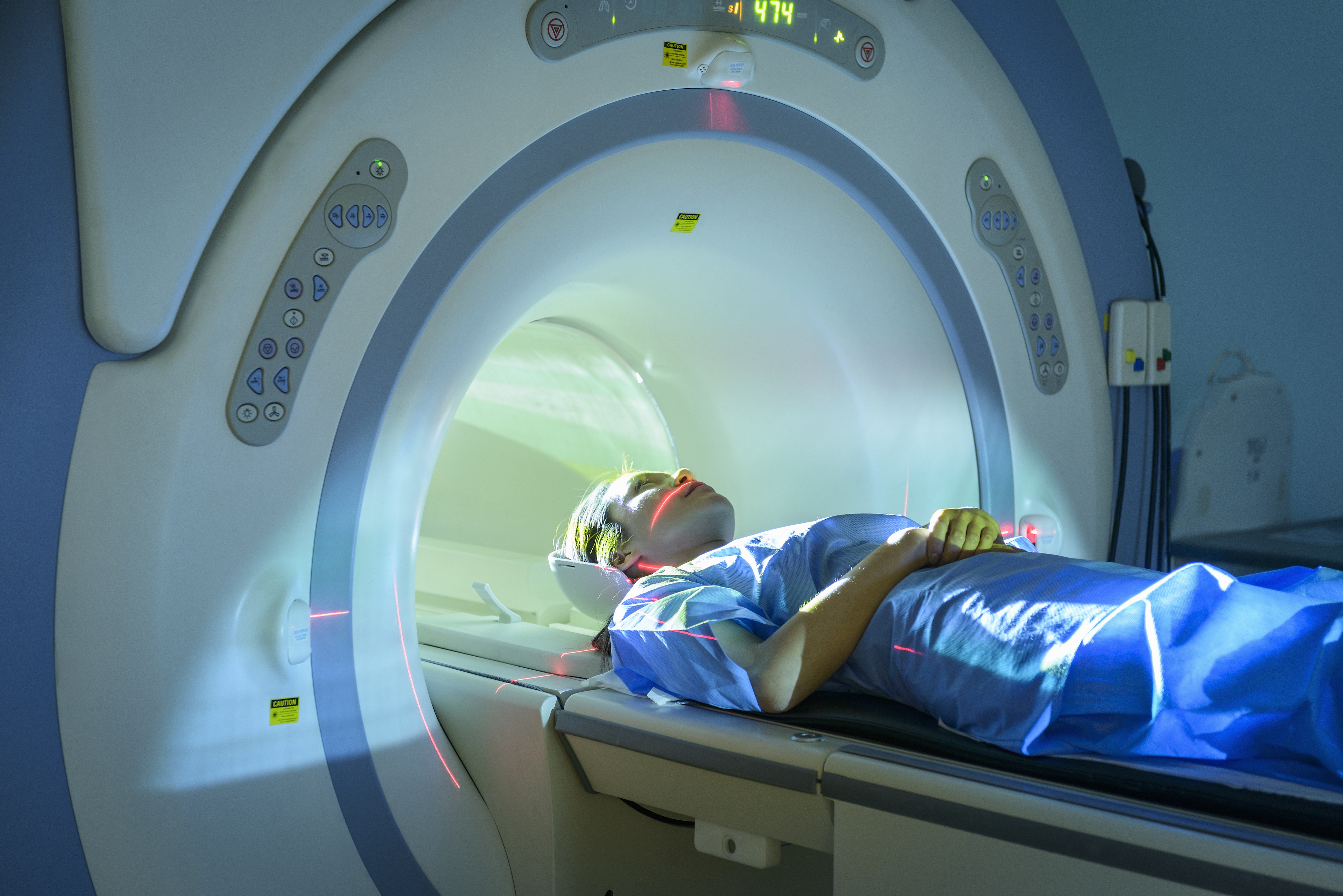

Clinicians may also be wary that Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) may underestimate the extent to which ‘early stage’ cancer may have progressed into the walls of the rectum and the cancer may in fact be more advanced than the MRI predicted.

A New Zealand study found that MRI accurately assessed the stages of only 43 per cent of cancers.

But when we compared patients in our study who had chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery with those patients that had surgery alone, we found there was no discernible benefit in their outcomes in terms of their cancer recurring.

Given the potential for severe side effects from chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer cases, including chronic bowel and sexual dysfunction, as well as the wider cost of treatment, our results are an opportunity to open up a discussion on when to use chemoradiotherapy before early stage lower rectal cancer surgery.

Health & Medicine

Growing nerves to restore erectile function

Around 5000 cases of rectal cancer are diagnosed in Australia every year, of which about 1000 are likely to be detected at the early stage.

Of these, half (around 500 cases) will be found in the lower part of the rectum.

Our study examined data from a sample of 352 patients with early stage lower rectal cancer from seven hospitals in Melbourne (three private and four public) as found in the BioGrid Australia ACCORD colorectal cancer database. This data goes back to 1990, but the majority of cases were after 2000.

We found that 58 per cent of patients with early stage (Stage 1) rectal cancer received chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery.

In terms of outcomes, we found that early stage rectal cancer patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy before surgery didn’t have an improved prognosis compared with patients undergoing surgery alone.

There were no differences in the number of tumours that re-occurred either at the site of the original tumour or at a different location in these patients.

We also found that pre-operative chemoradiotherapy was more common in public hospitals than in private hospitals.

Until now, no other study in the medical literature has provided strong evidence that the outcomes following radiochemotherapy prior to major surgery for early stage lower rectal cancer differ from surgery alone.

Health & Medicine

Curbing cancer’s addiction to treat it

While one study found no significant difference, the study size of just 84 patients was too small to draw decisive conclusions.

This makes our study the first to provide convincing evidence in support of the current recommended guidelines that surgery alone is the best method of treatment for patients with early stage rectal cancer in the lower part of the bowel.

After surgery alone, patients with Stage 1 rectal cancer have an excellent prognosis, with approximately 90 per cent expected to live for more than five years after their diagnosis.

While the small doses of chemotherapy given to rectal cancer patients prior to surgery are unlikely to cause side effects, the potential side effects of radiotherapy can be severe.

Immediate effects from rectal cancer radiation include diarrhoea, fatigue, nausea and nerve pain.

So, if chemoradiotherapy is unnecessary for early stage lower rectal cancer, then many patients are undergoing a treatment that potentially does them more harm than good.

Our study should help reassure surgeons, or at least put them more at ease, that withholding chemoradiotherapy and performing major resection surgery alone in this subgroup of patients may be the most beneficial treatment regime.

Co-authors on this study are Dr Elasma Milanzi, Senior Biostatistics lecturer, Centre for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Melbourne and Professor Peter Gibbs, Head of Personalised Oncology, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for Medical Research.

Banner: Shutterstock