Sciences & Technology

Getting to know your microbiome better

Our mouths contain billions of microbes. Increasing evidence suggests they are important for our oral and overall health, but modern diets are causing problems

Published 13 February 2020

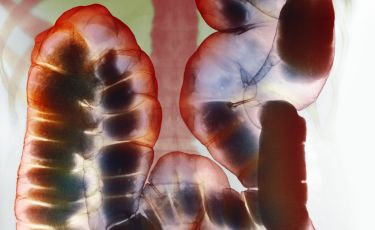

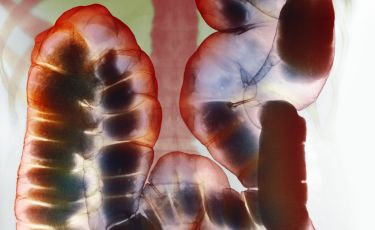

Oral microbiomes are extraordinarily complex.

Our mouths contain different types of microorganisms, but most are bacteria. It might not sound very appealing but having rich and diverse communities of bacteria living in your mouth is generally good for your health.

This is because varied types perform different roles and can keep each other in check.

Preliminary results of an ongoing study conducted in partnership by the University of Melbourne, Doherty Institute and Melbourne Museum suggest the communities of bacteria in our mouths could be improved, and a healthier diet might be the key.

The Victorian Oral Microbiome and Lifestyle Study aims to better understand the bacteria that live in our mouths and how they vary with different lifestyles, diets, backgrounds and where we live.

Sciences & Technology

Getting to know your microbiome better

Run alongside Melbourne Museum’s Gut Feelings exhibition in 2019, the study saw almost 1,500 visitors ‘spit for science’ so the microbes in their saliva could be studied by researchers.

In addition to their spit, participants provided a range of other information, including their diet and neighbourhoods where they live.

While there are already many studies that look at the oral microbiome, capturing the microbial diversity of Victorians is providing valuable insights into the Australian oral microbiome, says Dr Andre Mu, lead microbiome researcher for the study and research fellow at the Doherty Institute.

“When predicting health and disease, statistical models that use data from one location may not generalise to other locations.

“For example, we can’t strictly use data collected in the United States to predict a ‘healthy’ microbiome status for Australians.”

Research has revealed that microbes living within and on our bodies, which constitute around one to two kilograms of our bodyweight, contribute to how the body functions.

Health & Medicine

What maths can tell us about the spread of the new coronavirus

Around 700 bacterial species have been found in the human mouth, but each of us is likely to be inhabited by around 300 different species.

The bacteria in your mouth interact with each other and with you as their host – they help with digestion, can protect you against pathogens, produce chemicals that are important to your health, and sometimes cause disease.

Depending on what we eat, and how we look after our mouths and health, our oral microbiomes can act as guardians, particularly of our teeth and gums, or as invaders.

Just like us, microbes need food to eat and this is plentiful in the mouth. Your saliva, what you eat and the waste products of other microbes, all help nourish your oral microbiome.

Microbes often work together.

“Similar to the algae and molluscs that build up on the bottom of ships, our teeth and gums provide perfect surfaces for entire communities of microbes to be built,” says Dr Julian Simmons, principal investigator of the study and senior research fellow at the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences.

“These communities are called biofilms and are usually made up of a range of microbes that like living together. While some bacteria are initial colonisers, others only move in when conditions are just right.”

Health & Medicine

Making the most of probiotics

The new research suggests our oral microbiomes are becoming less diverse, and our oral health has declined, with modern diets.

We are providing our oral communities with far more sugar and other simple carbohydrates than ever before, and some bacteria convert these sugars into strong acids.

When we consume sugars frequently through the day, acid levels increase, eating away at our tooth enamel and disrupting biofilms.

Preliminary findings from the study support this, with high carbohydrate intake – like added sugar and refined flours – associated with lower diversity of bacteria in participants’ saliva.

So what can be done to improve your oral microbiome?

“Our current understanding of oral health indicates that supporting a healthy oral microbiome involves reducing the food for bacteria that can cause disease, and regularly disrupting the communities living on our teeth,” says Dr Samantha Byrne, senior lecturer at the Melbourne Dental School.

Dr Byrne advises that the most effective way to live in harmony with your oral microbiome, and keep your teeth and gums healthy, is to regularly clean the dental plaque from your teeth by brushing twice a day. And yes, flossing is important too because it removes dental plaque hiding between the teeth.

Antimicrobial mouth rinses are not needed unless recommended by your dentist, as they will remove bacteria that might be important for your health.

Reducing the total amount and number of times a day you eat sugar is also important for maintaining oral health, says Dr Byrne. This reduces the availability of simple sugars that oral bacteria can turn into acid, which in turn may help support a healthy oral microbiome and protect your teeth from decay.

Eating a varied and healthy diet is also crucial, for both your oral and gut microbial communities. Around 88 per cent of adults in the study reported not eating the recommended five serves of vegetables a day, and 30 per cent reported eating one or less serves a day.

It seems the food we now eat the most of, like added sugars and refined flours, doesn’t support the diverse communities of bacteria our mouths need. When it comes to our microbiome, we really are what we eat.

In 2020, researchers hope to take the study to regional areas to ensure that all Victorians are appropriately represented.

The Victorian microbe map installation is on display at Melbourne Museum until August 2020.

Banner: Getty Images