Politics & Society

How COVID-19 is hitting some democracies harder than others

With the US elections just 50 days away, the outcome will not just shape US democracy for a generation, but could diminish the very idea of democracy as a global norm

Published 15 September 2020

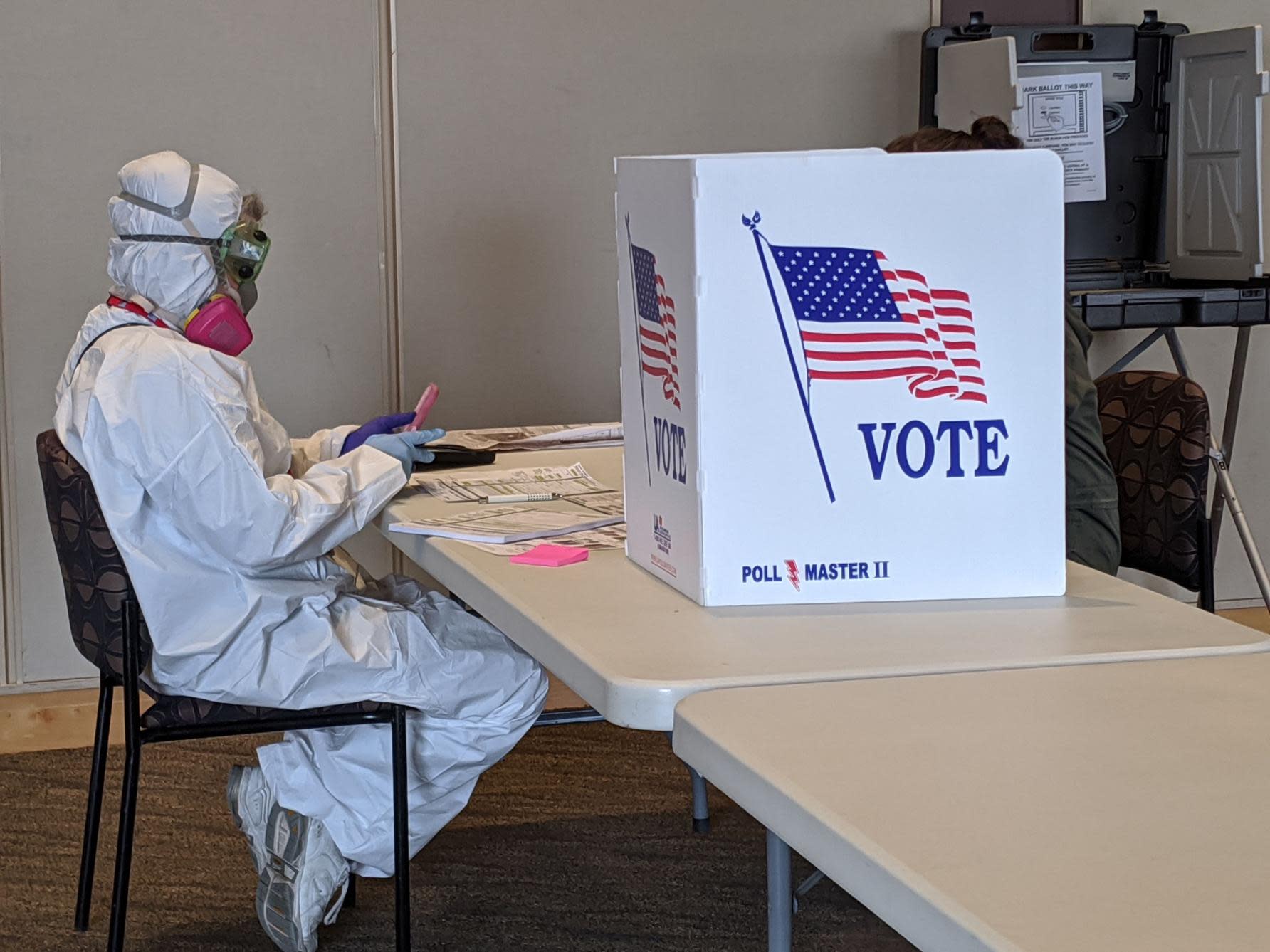

In 50 short days (US time), US voters will head to the polls in a democracy that, many experts agree, is in real trouble. “[A] close election could drive the [country] into a deep, prolonged constitutional crisis, and perhaps into civil violence,” says one political analyst.

“Rickety voting systems risk changing election results,” says another.

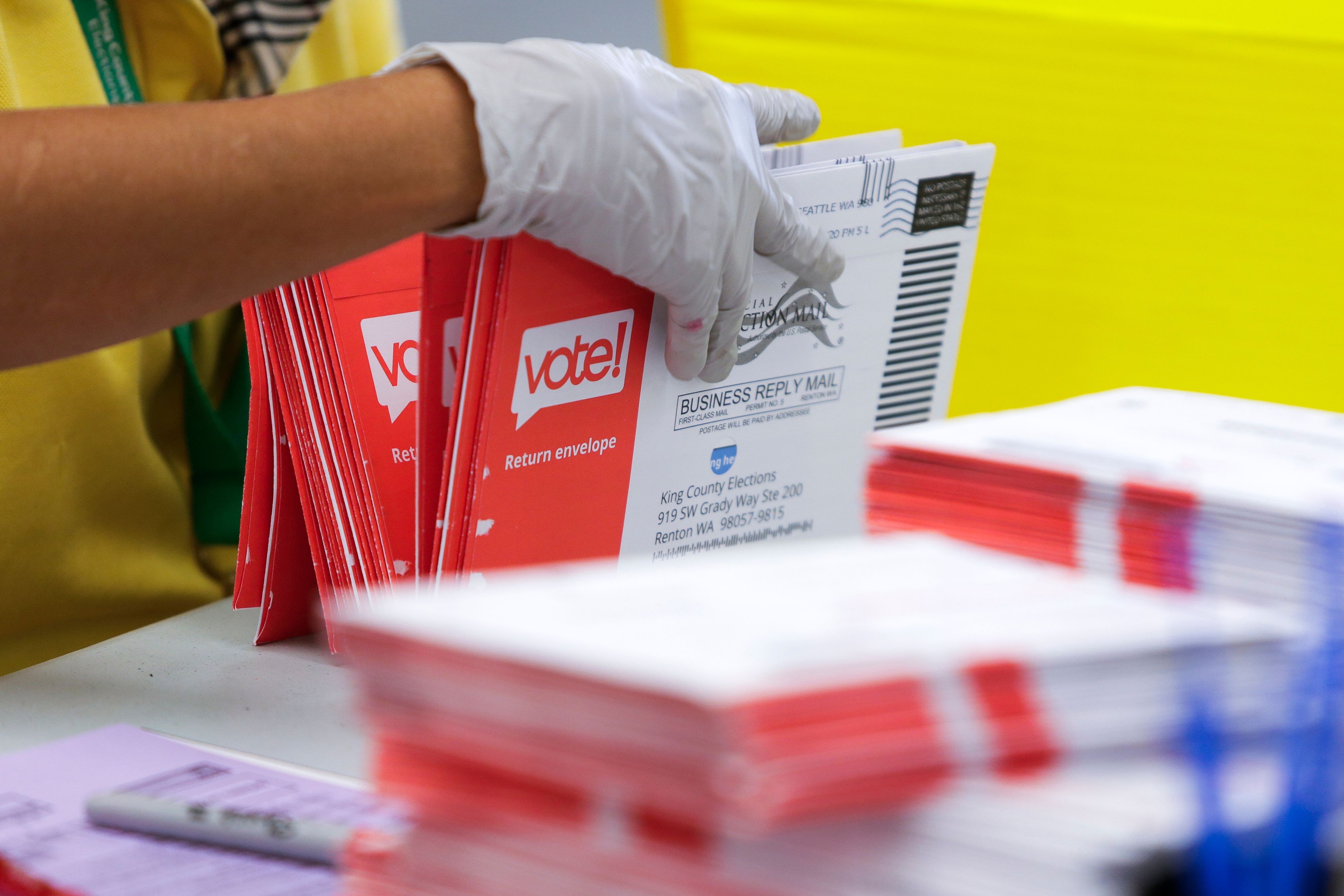

“Postal voting, which could swing the election, has become politicised in the president’s increasingly no-holds-barred campaign to stay in office” says a third.

And when asked if he will accept the election results, President Donald Trump simply responds: “I’m not going to just say yes.”

A crisis this acute in any country would be a cause for alarm.

Politics & Society

How COVID-19 is hitting some democracies harder than others

That these statements describe the USA, 50 days before the most important presidential elections for a generation, should concern every person on the planet.

After all, the US presidential elections are the closest we get to global elections.

From meaningful global action on climate change to the endurance of effective international multilateralism to the management of superpower rivalry, the result will potentially shape the lives of 7.8 billion people – 7.5 billion of whom get no say in who wins.

For those within the US, 83 per cent of registered voters say it really matters who wins the election.

But far beyond a routine partisan contest about which side gets to pursue their own legislative and policy agenda for four years, the election has been framed as no less than a battle for the soul and future of the nation – of its very identity as a liberal democracy.

The last three and a half years have witnessed the disabling of whole government agencies, political subordination of the justice department, claims of unfettered presidential power, the unprecedented use of the military against protesters, and a pandemic so mismanaged that the US – despite all its technological and scientific prowess – has suffered more than 190,000 deaths.

We have also witnessed the relentless sowing of doubt regarding the integrity of the forthcoming elections.

Arts & Culture

Race, change and time in the USA

The attempt to tear up that core social contract – at its most basic, the shared possibility of voting in a new government – is a loss for every voter, from the devoted Trump supporter to the classical pre-Trump conservative, from the urbane liberal to the firebrand radical.

This intensifying personalisation of power and party is further underscored by the fact that, for the first time since 1856, the Republican Party has not produced an original electoral platform. This election is ultimately a referendum on Trump himself.

What would a second Trump term really look like? We can’t know, but for clues, look to the records of foreign governments who have won elections after a first term spent attacking and delegitimising democratic institutions.

Whether Hungary after 2014, India after May 2019, or Poland after October 2019, the result has been a marked acceleration in the centralisation of power and a hardening of assaults on democratic institutions.

Hungary is no longer even considered to be a liberal democracy.

If the Trump presidency enters a second term and follows a similar path, the global atlas of democracy will begin to look profoundly altered. It would mean all four of the world’s biggest democracies – the USA, Brazil, India, and Indonesia – are moving away from liberal democracy.

Health & Medicine

A pandemic letter from an Aussie in the USA

To be clear, this is not to say that the US will come to resemble the authoritarian states of old.

Rather, as Professor of Politics John Keane puts it in his new book, The New Despotism, the result will likely be a more sophisticated form of undemocratic rule.

It would resemble a new species of centralised power married to extractive capitalism, which wins allegiance from enough people to achieve stability, functioning through complex networks of clientelism and patronage beyond the reach of democratic control, but with just enough democratic façade to claim legitimacy.

In this scenario, liberal democracy’s global hegemony (as a norm, as well as a lived reality) shrinks to the point that we are left with a pointillist smattering of democratic middle powers and smaller states, beset by despotic heavy-hitters.

The Trump administration did not create the international anti-democratic tide. But it has smoothed the path of the new despots for the past three and a half years, by treating these governments favourably – praising the Polish and Brazilian governments, for example.

Some will say, so what? The US’s track record on democracy at home and abroad has always been deeply flawed.

Domestically, historical ‘authoritarian enclaves’ – effectively one-party rule at the state level – were long a feature of the federation.

Politics & Society

10 reasons why COVID-19 favours a Trump election victory

Voter suppression, flagrant gerrymandering, and unequal treatment of citizens are indelibly written into the nation’s political DNA. Democracy scholars say the US has only been a real liberal democracy since the 1960s, with the reforms pushed by the Civil Rights movement.

Internationally, for all the US’s democracy-supporting work, it has repeatedly acted against democratic governments worldwide and deeply harmed countries like Iraq.

The shining city on a hill remains only an ideal, in the US, as elsewhere. But the overt discarding of those ideals under the Trump presidency matters. It changes the country’s ‘true north’, and any shared vision of the more perfect Union that the Constitution envisages.

Of course, Democratic presidential hopeful Joe Biden has pledged that, if he wins, he will be “an ally of the light, not of the darkness.”

But let’s not fool ourselves that this is like a Disney movie, a Manichean contest between the evil king and the good guys, where ousting the tyrant will bring all back into balance.

The fate of US democracy, the battle for its future, goes far beyond who wins the White House.

Politics & Society

Five takeaways from Super Tuesday

As Professor Keane has put it, the features that characterise the new despotism are already present in every democratic society, from “state-backed surveillance capitalism” to “dark money elections” to degraded information landscapes, all attenuating the prospect of meaningful control of government by the people.

Those trends have grown in the US, under both Democratic and Republican presidencies alike, for decades.

Trump, as has been repeatedly observed, is not their cause but their beneficiary and, by turn, accelerant. It will take creative and sustained leadership across the Union, from the federal to the local levels, across all fifty states, to address these issues and re-think how democracy works. It is a generational project.

But a Trump win in November will set the US on the opposite path.

So, what does that mean for Australia?

A USA that may be even less reliable than it is now. A more challenging regional context that cannot be addressed solely through beefed-up hard power. There’ll also be a need to think seriously about a much more expansive soft power strategy that strengthens relationships with liberal democracies, especially across the Asia-Pacific region.

Politics & Society

The state of democracy, before and during COVID-19

At home – and indeed, in every democracy – the US also acts as a mirror. Perhaps the distorted reflection of a fairground mirror, but a mirror nonetheless.

The US’s challenges should prompt every democracy to take a long, hard look at itself. At both our frailties and our strengths.

And today, the International Day of Democracy, we need to remind ourselves that democracy’s strengths are legion. In the US, and across the world, the fight for democracy – real government for the people, by the people – never ends.

In fact, it’s only beginning.

If you’d like to know more about the global #DefendDemocracy campaign in honour of the International Day of Democracy, visit: https://www.idea.int/news-media/news/international-democracy-week-2020-events-focus-innovative-solutions.

Banner: Getty Images