Politics & Society

US tariffs have backfired, and China is winning in Southeast Asia

A new book argues that our focus on AUKUS and ongoing dependency on the US makes Australia less safe

Published 23 July 2025

On 15 September 2021, President Joe Biden of the United States joined via a linked video conference the prime ministers of Australia and the United Kingdom, Scott Morrison and Boris Johnson respectively, to announce the formation of a new security relationship to be known as AUKUS, after the initials of the participating countries.

The goal of the venture was ostensibly to help sustain the peace and stability of the Indo-Pacific region and to maintain the US-led global rules-based order.

In creating AUKUS, the security challenge Australia and its partners sought to counter was an increasingly assertive China, under its President, Xi Jinping.

The political and military leaders of the United States believe that China is the greatest menace in the world at present.

China is no longer rising – it has risen. China’s leaders have grown in confidence and capability, and its military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), has modernised its forces and enhanced its lethality.

That China is challenging the dominance of the United States in the Western Pacific is well known and the subject of much analysis by military and security commentators.

The US military has identified China as its ‘pacing threat’, by which it means the country against which its forces are to prepare to fight. In addition, the United States is seeking to shore up its alliance system and incorporate its partners into an integrated deterrence network.

Politics & Society

US tariffs have backfired, and China is winning in Southeast Asia

There is no shortage of flashpoints that could spark a conflict between the great powers, the most concerning being the future of Taiwan and the potential for the renewal of hostilities on the Korean Peninsula.

Morrison explained that Australia needed AUKUS because of the worsening security environment in the Indo-Pacific.

Then opposition leader, Anthony Albanese, did not hesitate to profess his own support for AUKUS, as well as agreeing on the utility of the deeper relationship with the United States and the United Kingdom that the new arrangement implied.

Domestic politics was undoubtedly a factor in the government’s decision to pursue AUKUS. Albanese, with an eye on the next election, rightly saw the pact as a potential political threat and would not give Morrison a national security issue with which to wedge Labor.

Under AUKUS, Australia would become only the second country to which the United States had granted access to its nuclear submarine secrets, the first being the United Kingdom.

On the surface, AUKUS seems like a great deal for Australia, and this is certainly the way Morrison and Albanese have portrayed the agreement.

Yet the surface’s appealing gloss has diverted attention from AUKUS’s many imperfections and inconsistencies, and the leaders of both parties have displayed a lack of critical judgement and national loyalty in their rush to profess their allegiance and their enthusiasm.

AUKUS harkens to a time when US power was unchallenged, and constitutes an effort to turn back the tide of history rather than understand it or confront its present realities.

In a world facing an existential crisis from climate change, AUKUS epitomises a pact more suited to the Cold War than to the contemporary threat environment.

It is neither a courageous defence policy nor a bold exploration of new possibilities. Instead, Morrison and Albanese have perambulated along the well-trodden path of Australia’s unbroken reliance on a great power friend for the provision of what, for most states, is a government’s ultimate and most important purpose – the security of its territory and people.

Politics & Society

Understanding my father

Australia’s leaders have once again positioned the nation so that participation in the United States’ next war will be virtually mandatory, even if this is a war between two nuclear-armed great powers.

Lastly and most significantly, Australian leaders have assumed the potential menace of China without a commensurate effort to assess either the likelihood of the threat being realised, the potential to mitigate the China challenge without recourse to war or the possibility that there are other risks that are worse.

In fact, it would not be too bold to say that AUKUS has made Australia less safe instead of more so.

AUKUS is simply the latest manifestation of Australia’s routine determination to secure its protection by embracing dependency on a great power. By dependency, I mean the propensity of Australia to seek support from a great power to secure its safety in a world in which it sees threats to the nation’s welfare.

It was neither an innovative security policy in 1942 when Prime Minister John Curtin announced that Australia would turn to the United States after the failure of the Singapore strategy, nor in 1966 when Prime Minister Harold Holt expressed the nation’s enthusiasm to go “All the way with LBJ” by supporting the United States in the Vietnam War.

Australia has never displayed any hesitation in leaning on or clinging to a great power protector, and has proven consistently willing to pay the price, often expressed as the premium on the insurance policy.

In embracing dependency, the nation’s leaders also dismiss its potential to compromise Australian sovereignty or that it reduces the country to an imperial outpost of its increasingly unstable great power protector.

The two prime ministers have acted on the automatic default setting that has dominated Australia’s security decision-making since Federation in 1901, if not before – that is, to seek security by serving as a loyal sub-imperial dependency in a great power’s empire.

The craving to secure the protection of a great and powerful friend is seemingly hardwired in the psyche of Australia’s political leaders.

Politics & Society

The China divide

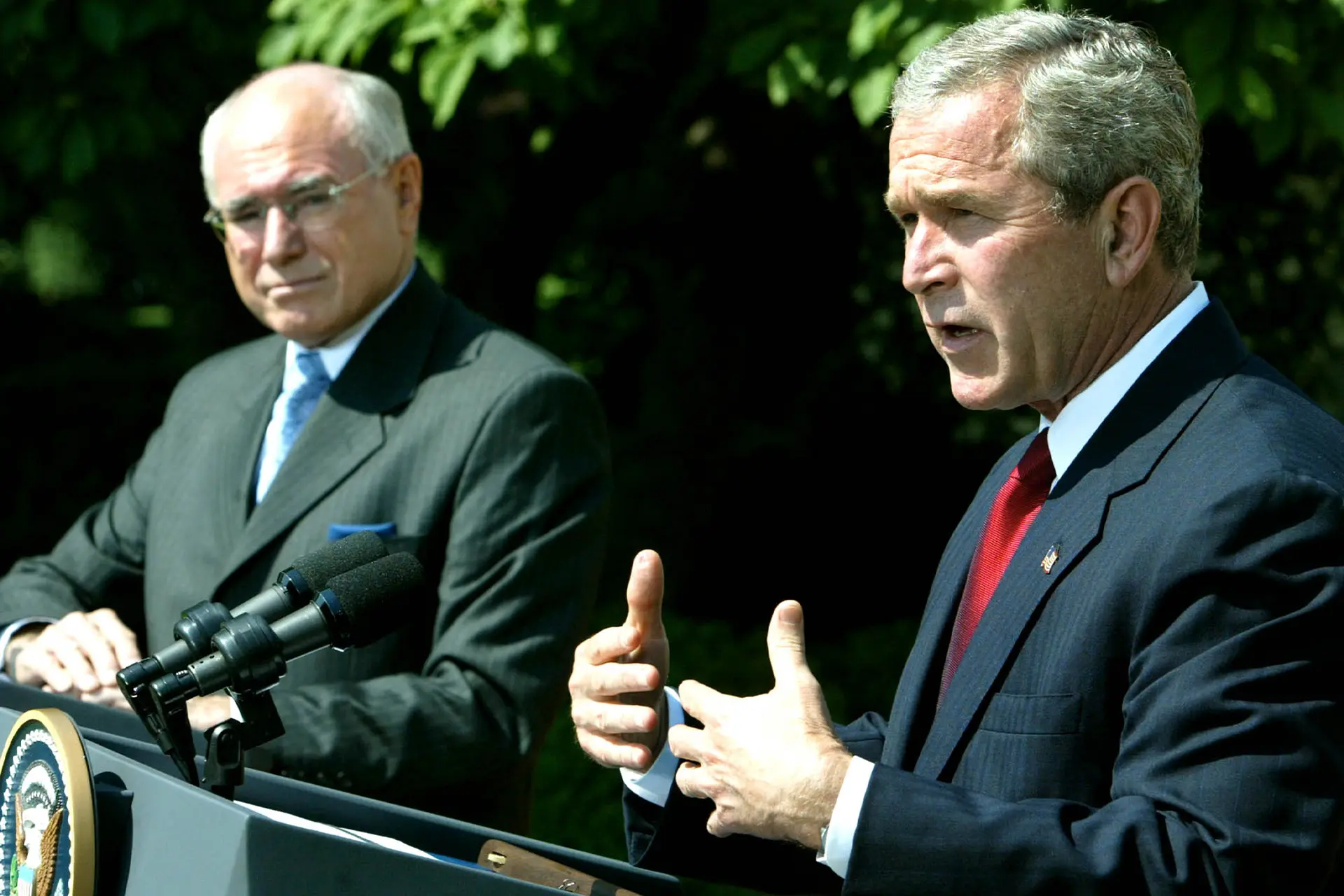

Time will tell if Albanese will be America’s next ‘deputy sheriff’ – an honorific first suggested by the journalist Fred Brenchley during his interview of Prime Minister John Howard for The Bulletin in 1999, a term US President George W Bush took up in 2003 – but he is certainly moving in that direction.

The government’s lack of imagination and reluctance to embrace anything different has resulted in a defence policy that is ill-conceived, badly thought-out and contradictory, and which mandates investment in capabilities that will be of little utility or survivability in the wars Australia will likely have to fight.

In addition, the nation’s political leaders have embarked upon this policy with minimal explanation of its rationale.

In short, Australia’s defence policy is broken.

This is an edited extract from The Big Fix: Rebuilding Australia’s National Security, by Albert Palazzo, and published by Melbourne University Press.