Australia must include people with cognitive disability in politics

People with cognitive disability want to have their say in Australian politics. And we must do more to recognise their political inclusion

Published 20 September 2023

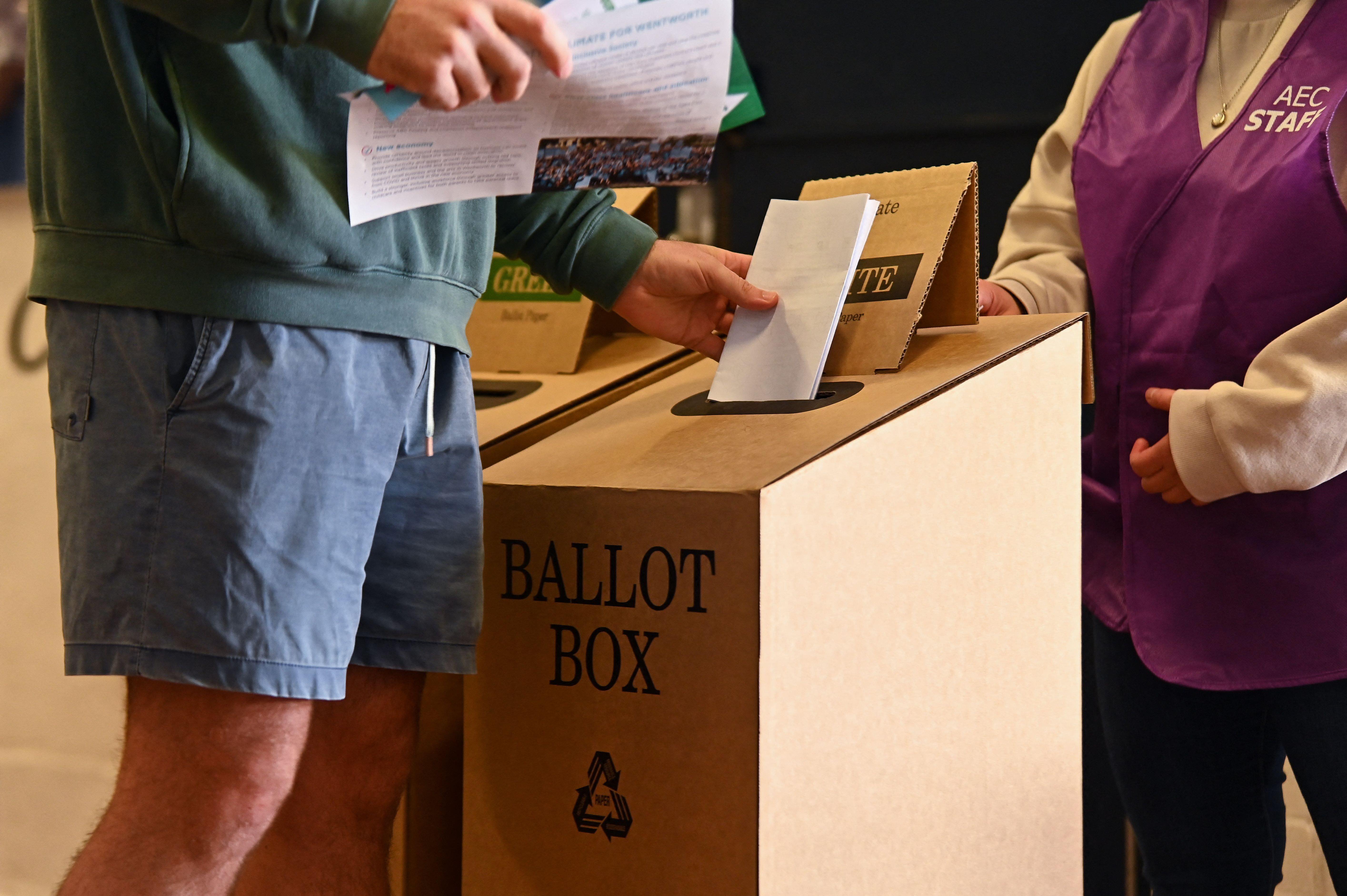

Most Australians will take it for granted that come the referendum on the Voice to Parliament, they will be able to turn up at a polling booth and have their say – ‘Yes’ or ‘No’.

What you may not know is:

thousands of Australians have had their name removed from the electoral roll on the basis of unsoundness of mind, a clause in Australia’s many electoral laws. Other Australians have simply never enrolled on the basis of other people’s assumptions about their mental capacity

there is no government or parliamentary body currently that has responsibility for enabling the political inclusion of people with cognitive disability, nor is there any formal education standard or disability sector regulatory requirement protecting the right to even a basic level of political education for people with cognitive disability

there is no requirement for Australian political parties and election candidates to produce campaign material in accessible or easy language.

People with intellectual disability, acquired brain injury and other cognitive disability, including First Nations People with disability, want to have their say in the referendum and in Australian political life more broadly.

People with cognitive disability want the respect and dignity given to other Australians. They want to have their voice heard by their local Councillor, their local member of state parliament, and in the Commonwealth parliament.

This is a fundamental right under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), to which the Australian government is a signatory.

With funding from the Melbourne Disability Institute (MDI), the University of Melbourne and Inclusion Melbourne’s Inclusion Designlab worked with a network of national partners to host a two-day national summit to find solutions to the exclusion of Australians with cognitive disability from Australian political life, including in voting.

The Political Inclusion National Summit was the culmination of a longer-standing project, Inclusion Designlab’s I Can Vote, and brought together 100 people, including people with disability, Human Rights Commissions, Commonwealth and state electoral commissions, disability support organisations, family carers and many others.

The Summit heard from international experts from Sweden, Canada and the UK. These experts demonstrated how people with cognitive disability can and do actively participate in the political life of their communities.

The summit also heard from Australians with cognitive disability and advocates who have engaged in politics and clearly demonstrated the power of consistent, scalable models of support to build a person’s political engagement.

For some, simply being included in everyday political conversations and getting help to understand the prevalent jargon provides a substantial boost to their political knowledge and desire to engage.

For others, approaches like Supported Decision Making and Circles of Support help a person’s journey of enfranchisement.

Politics & Society

Rebuilding Victoria’s forgotten integrity institution

But it is clear that, as a signatory to the UN-CRPD, Australia can and must do more to recognise and support political inclusion and voting by people with cognitive disability.

While Article 29 mandates support for political inclusion, several other Articles in the Convention back this up – like the right to have one’s legal capacity respected, the requirement for government to engage in awareness raising, and the right to education.

As such, the Summit was an opportunity to both carefully frame the barriers to inclusion and to develop a plan for a future targeted campaign focused on removing these barriers.

The disability advocacy motto ‘Nothing about us, without us’ was established as a central part of advocacy for political inclusion. Government needs to formally acknowledge and assume responsibility for addressing each barrier and work together with people with cognitive disability and their allies.

However, in Australia, excessive perception of risk associated with supporting people with cognitive disability to develop political awareness, coupled with the Electoral Commissions’ requirement to avoid getting involved in the communication of partisan political content, has prevented any action on these steps.

This contrasts greatly with the UK Electoral Commission’s enthusiastic support and funding of initiatives led by civil society that focus on making political information more accessible for people with cognitive disability.

Critically, addressing the substantial barriers experienced by Australians with cognitive disability requires realising the right to be supported to learn about politics rather than simply focusing on the accessibility of a polling place on election day.

Arts & Culture

Measuring diversity in Australian publishing

There has been some good work on this in the UK and Canada. For example, peer support and learning groups linked to political inclusion, more opportunities for engagement in community issues and campaigning by self-advocacy groups have all had an impact.

The voice of people with cognitive disability needs to be heard, respected and acted upon – at all levels of government.

Local councillors and members of state and Commonwealth parliaments must listen to their constituents with cognitive disabilities.

Meanwhile, politicians and government need to have more inclusive engagement and conversations with people with cognitive disability. Information about policies needs to be in accessible language, something the I Can Vote project has done in previous Victorian elections.

To do this we need to work with support professionals, family and carer organisations, and educators so they can help people to engage in civic and political learning and action.

We need teachers in schools to have the skills to support children with disability to learn what it means to have agency as citizens – to be active and engaged from early in their life.

This education and training needs to be available lifelong to support people with cognitive disability to develop their political awareness and their engagement with all levels of government.

Politics & Society

Making information accessible - for everyone

The UK, Sweden and Canada are already quite ahead of Australia in this regard.

Political information that is easy to understand and access, as well as support to learn about civic engagement and politics, must be made available to people with cognitive disability.

People with cognitive disability need support to learn about voting, not barriers to prevent them from voting and illegitimate assumptions of non-capacity like those that sit behind the unsound mind clauses in several Australian electoral laws.

They need a voice in their community that is heard and respected at all levels of government – local, state and Commonwealth.

The partners of the Political Inclusion National Summit are preparing their next steps – including a national campaign.

Support and funding of this campaign will allow many people with cognitive disability to “effectively and fully participate in political life” and go on to vote in elections and referendums – playing their part in Australian democracy.

The Political Inclusion National Summit 2023 partners include: Aruma Disability Services, Carers Australia, Deakin University, Hunter Circles, Inclusion Melbourne, Inclusion Australia, Melbourne Disability Institute, Microboards Australia, Queenslanders with Disability Network, Rainbow Rights and Advocacy, VALID.

Banner: Getty Images