Politics & Society

Why Parliament should decide on same sex marriage

Since Federation, Australia has on average voted in a plebiscite or referendum every six years - but our most recent was back in 1999. Is there an argument for regular referendums?

Published 16 August 2017

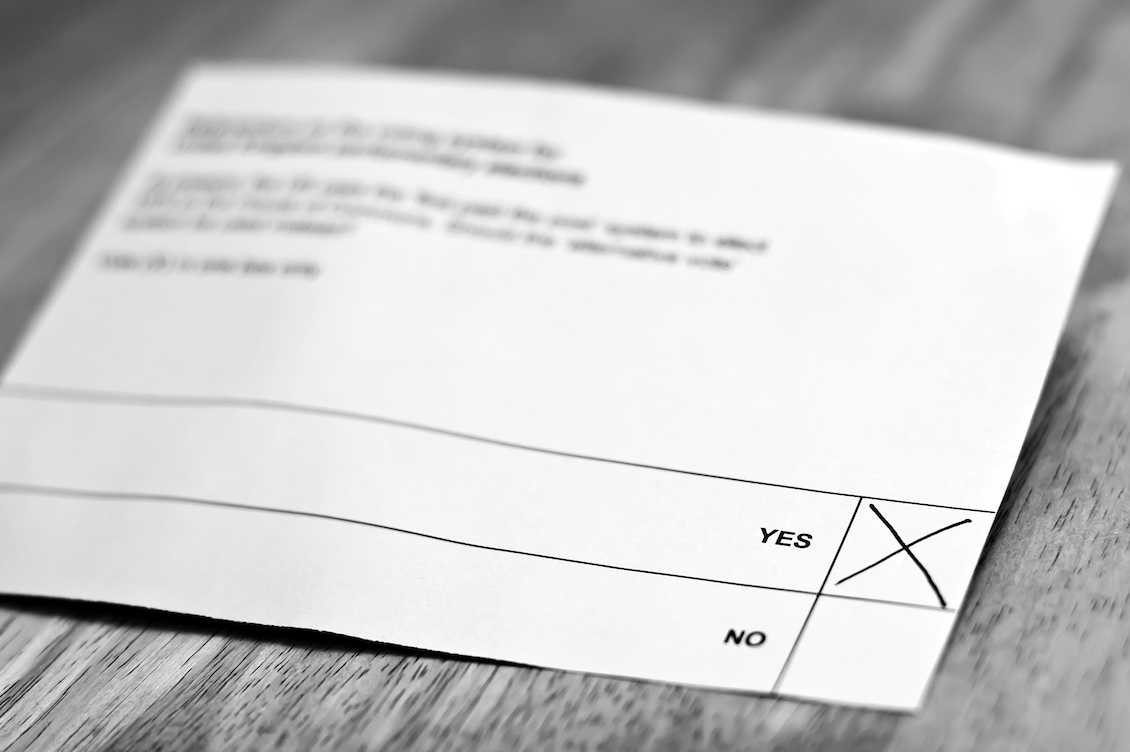

It has been almost 18 years since the last federal referendum – an eternity in political years. But the upcoming postal survey on same sex marriage is a timely reminder that citizens have the power to vote on actual public policy. And this power should be enhanced.

Citizens should be able to vote on a national plebiscite or referendum on a different public policy issue at every election. This could help empower voters, re-igniting their passion and participation back into the democratic system.

The most recent referendum was in the last millennium, before the Y2K computer scare, before 9/11 and before the Sydney Olympics. Back in 1999, Australians voted on whether to become a Republic. A young and ambitious Sydney businessman named Malcolm Turnbull was Chairman of the ‘Yes’ campaign. The ‘No’ campaign prevailed. But Bill Shorten has recently resurrected the issue.

Oddly, this is the longest period Australia has gone without holding a national vote. Anyone under the age of 35 has never participated in a federal referendum.

It didn’t used to be this way. On average since Federation, Australians have gone to the polls to vote on a referendum or plebiscite every six years – it’s now been three times that.

History has proven that referendums are hard to win. Of the 44 held, only eight have passed – a woeful 18 per cent. They are also hard by design – they need a majority of the population and a majority of the states to pass.

Politics & Society

Why Parliament should decide on same sex marriage

Recently, a constitutional referendum proposed to be held in 2013 to allow federal funding to local councils was abandoned due to timing problems and unexpected leadership changes. The same proposal has already been tried and failed twice in 1974 and 1988.

Australia’s worst performing referendum was the 1988 ‘Rights and Freedoms’ in which only 31% of voters supported the proposal, and was not carried by one state. The best performing referendum was in 1967 to include and recognise Indigenous Australians in the official census.

It’s worth bearing in mind, a referendum is needed for a legally binding constitutional change. A plebiscite is non-binding and is used as a tool to advise politicians on altering specific legislation. Plus, voting in referendums is compulsory, while the federal parliament can determine whether a future plebiscite is compulsory or not.

Irrespective of whether a referendum or plebiscite is being called, the key point is: we should hold national votes more regularly.

Last year Tasmanian Senator Jacquie Lambie stated she wanted more plebiscites - including on marriage equality, voluntary euthanasia and constitutional recognition for indigenous Australians.

This proposal of regular votes has merit.

We should be given three votes at every federal election. One for your local House of Representatives MP, one for the Senate, and one more for a vote on a specific policy topic.

The idea is commonly used at the state level in the United States. At last year’s presidential election, American voters in Massachusetts were also given four additional policy questions. Two issues passed, one of which included support to legalise the recreational use of marijuana – a common ‘sticking’ point that most politicians choose to avoid.

And there are reasons to support an increase in participatory democracy.

People are more motivated about politics when voting on a specific area of public policy. It’s more engaging than voting for your local candidate; in fact, some international surveys have shown that only around 25% of people can’t even name their local federal MP.

It also allows politicians to devolve themselves of highly contentious policy issues – for example, same sex marriage, euthanasia and abortion.

And it can help to get new issues on the political agenda that politicians might otherwise ignore, like making the Northern Territory Australia’s seventh state.

Implementing a new referendum at every election can be done in a variety of ways. And there are two key models:

Politics & Society

How we can reinvigorate democracy

Either change the Constitution or the Electoral Act 1918 to obligate one new referendum or plebiscite at every federal election. And a bi-partisan Parliamentary Committee could be formed to select the topic and question.

Or we could adopt the Swiss model of direct democracy, whereby popular initiatives must be considered by the parliament once 100,000 signatures have been collected within an 18 month period.

But, a word of caution is needed.

Public policy is difficult. And this is no understatement. Any reform must be done on a relatively ‘simple’ and easy to understand topic. The successful Brexit vote in the UK last year illustrates this point.

Removing oneself from a large multi-national entity involves re-negotiating trade agreements, migration, financial policy, national security and more. This shouldn’t be left to a public vote. The combination of these topics is beyond the capacity of a distinguished public policy maker, let alone your average citizen.

Whereas, a more straightforward topic is marriage equality. Changing the wording of the Marriage Act 1961 to allow any two couples of any gender to be legally recognised in a marriage is easy to understand and has few outside variables. It doesn’t impact on national security, migration, or the economy in any way like the UK’s decision to the leave the EU does.

Business & Economics

Why more Australians are supporting gay rights

Referendums will the still fail even with a simple topic. But that shouldn’t deter us from trying.

Change is hard. New Zealand failed in its 10-month, two stage referendum to change its flag. But the process was fair, easy to understand and participatory. Commentators said it was a waste of time and some AUD$23 million. But this is wrong. The flag referendum was not to change the flag - it was to allow New Zealanders the opportunity to decide whether to change or keep the original flag.

Lastly, the costs will be minimal if referendums are held at each federal election. It they are held outside an election, such as the same-sex marriage postal plebiscite, then costs will be greater.

Ultimately, a referendum at every election is an innovative way and cost effective way to continue to strengthen our democracy.

Banner image: Shutterstock