Politics & Society

Returning water rights to Aboriginal people

Rivers around the world are now recognised by law as legal persons and living entities. Here in Australia, our rivers can be understood as ‘ancestral beings’ under Indigenous laws

Published 18 October 2021

During National Water Week, it’s time for all of us to examine our relationship to water – our rivers, wetlands, lakes, aquifers, estuaries, rainfall – and the many ways in which our water is managed.

As rivers are increasingly recognised as legal persons in multiple jurisdictions across the globe, many of us are grappling with how to ensure that the law sees rivers as unique legal beings.

One way to do this is by developing a novel legal concept – the ‘ancestral person’.

This could unite the idea of Nature as a legal subject with Indigenous world views that see Nature as a complex tapestry of ancestral relations enmeshed in a network of interdependence and guardianship between the human and the non-human world.

Since the release of the Constitution of Ecuador in 2008, the rights of Nature movement across the world has gained exponential momentum, and a great number of jurisdictions worldwide today recognise some form of legal subjectivity vested upon Nature.

Politics & Society

Returning water rights to Aboriginal people

Over the last decade, and in particular since 2017, river personhood has become one of the most recognisable forms of this subjectivity. When we say river personhood, this means the law regards a river as a legal person – an entity capable of bearing rights and duties.

The first case to successfully invoke the rights of Nature, from which legal personhood later arose, occurred in Ecuador in March 2011, when two plaintiffs sued the district government for damage, erosion and flooding of the Vilcabamba River, not in their capacity as affected landowners, but rather asserting a breach of the rights of Nature provisions in Ecuador’s Constitution.

Six years later, the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 (NZ) recognised the Whanganui River and its tributaries as “an indivisible and living whole, comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and meta-physical elements”.

This is one of the most remarkable examples of law’s ability to transcend traditional ideas of natural resource rights and governance by incorporating concepts from the laws of Indigenous peoples.

Other major milestones on this remarkable journey include the 2017 Indian Ganges and Yamuna Rivers case, the 2016 Atrato case in Colombia (as well as the similar cases that followed), and the 2019 Bangladesh Supreme Court decision – which ruled that all the rivers in Bangladesh had the status of legal persons and living entities.

In Australia, the concept of a river as a living entity in its own right made its first appearance in Victoria in 2017, when the Victorian Parliament enacted the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017.

Environment

The legal rights of rivers

For the Wurundjeri people, the Birrarung is “a river of mists and shadows” and the Act’s preamble, as translated from Woi Wurrung language, emphasises their connection with the Birrarung as a living entity:

“We the Woi-wurrung, the First People, and the Birrarung, belong to this Country. This Country and the Birrarung are a part of us. The Birrarung is alive, has a heart, a spirit, and is part of our Dreaming. We have lived with and known the Birrarung since the beginning.”

A novel form of ‘environmental’ personhood vested upon rivers is rapidly emerging. But maybe an even richer story can be found.

Established in 2018 by six independent Indigenous nations, the Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council (Martuwarra Council) believes it is now imperative to recognise the pre-existing and continuing legal authority of Indigenous laws – or ‘First Law’ – in relation to the River in order to preserve its integrity through a process of legal decolonisation.

River personhood is now understood as one pathway towards this outcome.

However, the traditional legal idea of personhood adopted until now needs to be reconceived in relation to the River. After all, First Nations peoples of the Martuwarra Fitzroy River recognise that the River is already a living ancestral being with a right to life and flow.

The time to talk of rivers as an ‘ancestral being’, with ties of mutual obligation and reciprocity, has now come.

Our dialogue with the Martuwarra Council and the river has developed this new category as a future concept for settler state law in Australia.

In a forthcoming paper, we (and others) explore the emergence of this potential novel category drawing on the global experience, noting that this growing, and inherently pluralist, awareness must surely transform our understanding of what constitutes ‘Nature’ in general and a river in particular.

The law is being used creatively to train human beings to listen, pay attention to, and learn from, different rivers.

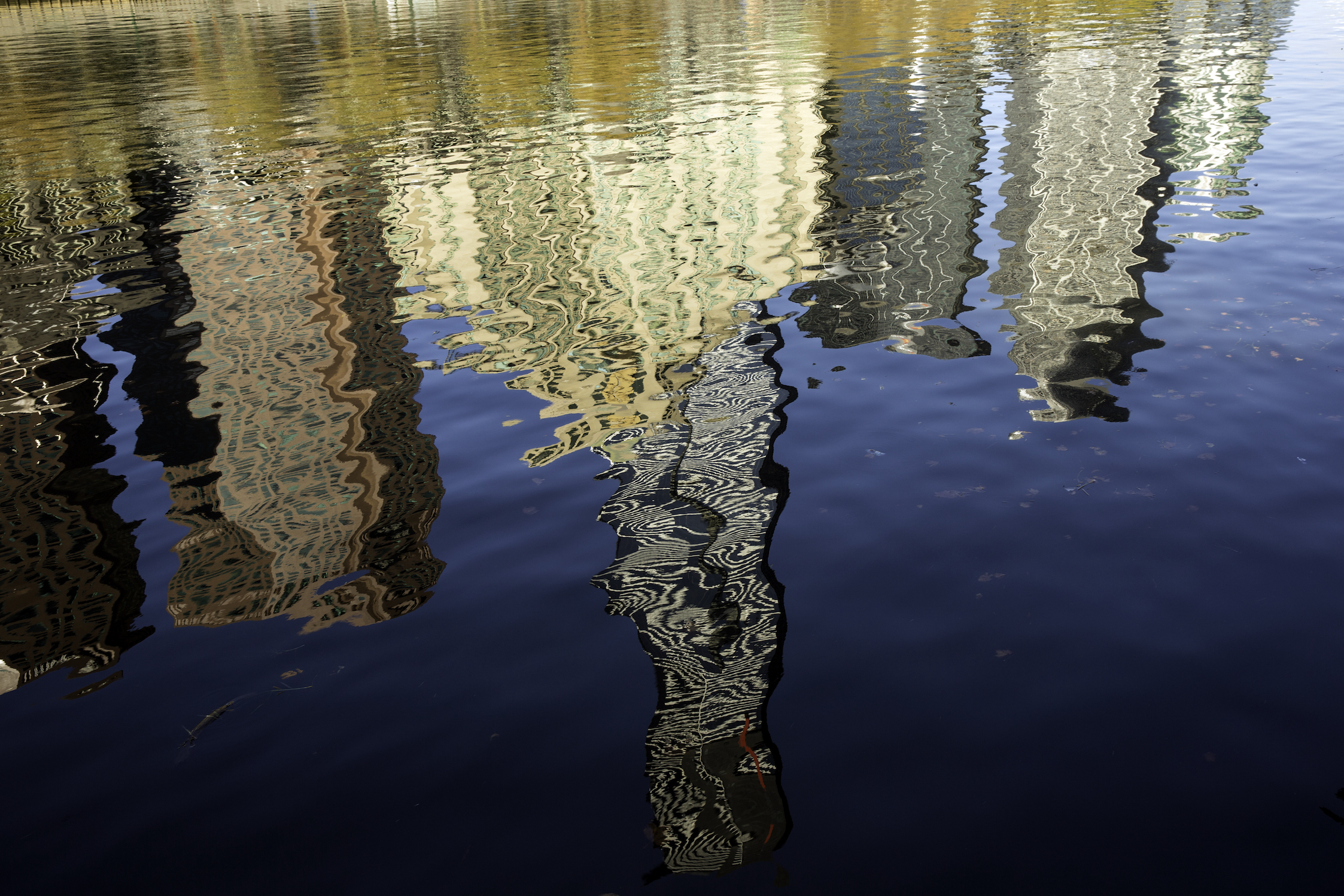

Significantly, at the same time, this new concept of rivers also embodies the stories that have always connected Indigenous peoples to their land, rivers, trees and totems. These stories often recognise that time isn’t just a linear arrow, but rather a swirling flow – so at any point ‘in time’ a river can also connect us to its past and our futures.

The bridges, between the past and present, and between First Law and settler state law, are present in the idea of these riverine ancestors and the way they cast themselves upon us and our consciousness.

And so, while a river holds meaning for itself with or without us, the novel idea of an ‘ancestral person’ can strengthen the connections between the river’s life and the peoples who live along and love the river.

Seeing rivers as ancestral beings reinforces the relationship we have with them.

Sciences & Technology

Always was and always will be Aboriginal water

We can begin to move away from seeing rivers as merely an object that we may use as we wish, to seeing them as living entities, with whom we are all in a lasting, reciprocal relationship.

When the law recognises rivers as ‘ancestral persons’, it sends a strong message that the river itself is a collaborator in its own management. We can truly begin to work with the river to make a better future.

All the authors are grateful to our co-authors on our forthcoming paper in Griffith Law Review: Professor Afshin Akhtar-Khavari, Dr Cristy Clark, Dr Sarah Laborde, Associate Professor Elizabeth Macpherson, Dr Katie O’Bryan, Professor John Page, and Martuwarra River of Life itself.

We also gratefully acknowledge the seed funding our work has received from the Indigenous Knowledge Institute at the University of Melbourne.

Dr Erin O’Donnell is a member of the Birrarung Council, the voice of the Yarra River. Dr Anne Poelina is the Chair of the Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council.

Banner: Getty Images