Health & Medicine

Don’t be that person

Victoria’s recent COVID-19 outbreak dramatically increased vaccinations in the state, and across Australia, more people are now keen to get the jab

Published 22 June 2021

Following Victoria’s fourth lockdown, demand for COVID-19 vaccinations has increased sharply, with governments scrambling to increase access and supply.

Before the latest outbreak in Victoria and following safety concerns over the AstraZeneca vaccine, vaccine complacency extended to those who wanted to be vaccinated but had decided to wait for the Pfizer or another vaccine.

At the time, there was no compelling reason for many people to get the vaccine straight away, or they were happy to wait as other priority groups were vaccinated first.

But the situation, as we were warned by medical experts and with winter upon us, has changed rapidly.

In our research, we’ve used several waves of data from the Taking the Pulse of the Nation Survey (TTPN), which is run by the Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research.

Health & Medicine

Don’t be that person

Our study included data from before the recent Victorian outbreak and during the first week of the state’s lockdown to draw four key insights on Australia’s behaviour and attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccines.

National data show that over five million vaccine doses had been administered by 7th June.

Our TTPN data show that 20.4 per cent of adults aged over 18 have received at least one dose.

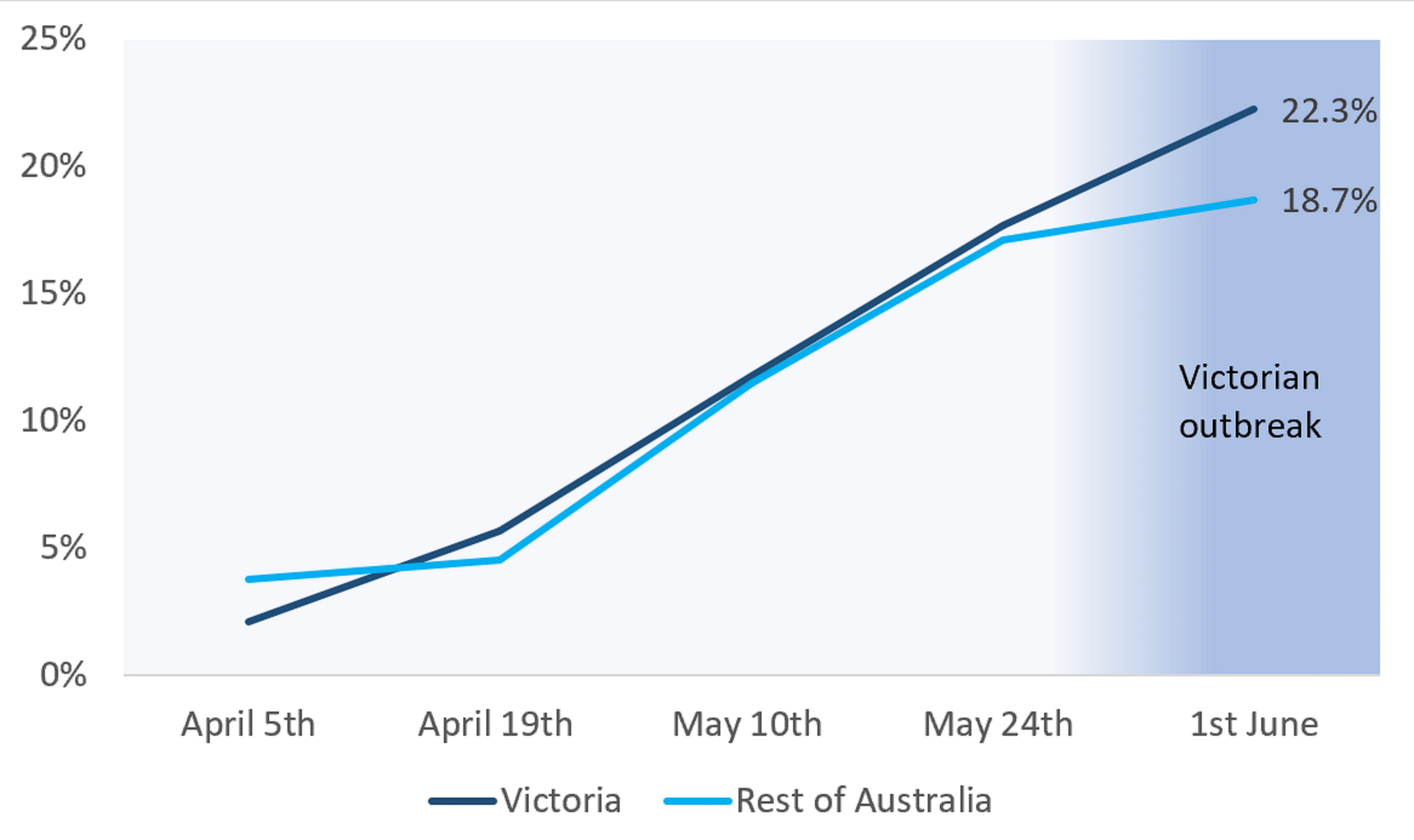

In the first week after lockdown began in Victoria on May 28th, the proportion of people vaccinated in the state increased from 17.7 per cent to 22.3 per cent or 4.6 percentage points (Figure 1). This is compared to an increase from 17.1 per cent to 18.7 per cent in the rest of Australia (1.6 percentage points).

During the recent outbreak in Victoria, Victorians were getting vaccinated more than twice as fast as the rest of the Australian population.

This reflects an increase in demand, the decision to make vaccination one of the five reasons people could leave home during the lockdown and the special efforts to make vaccines available in Victoria by State and Commonwealth governments.

Health & Medicine

The global race to understand COVID-19 variants

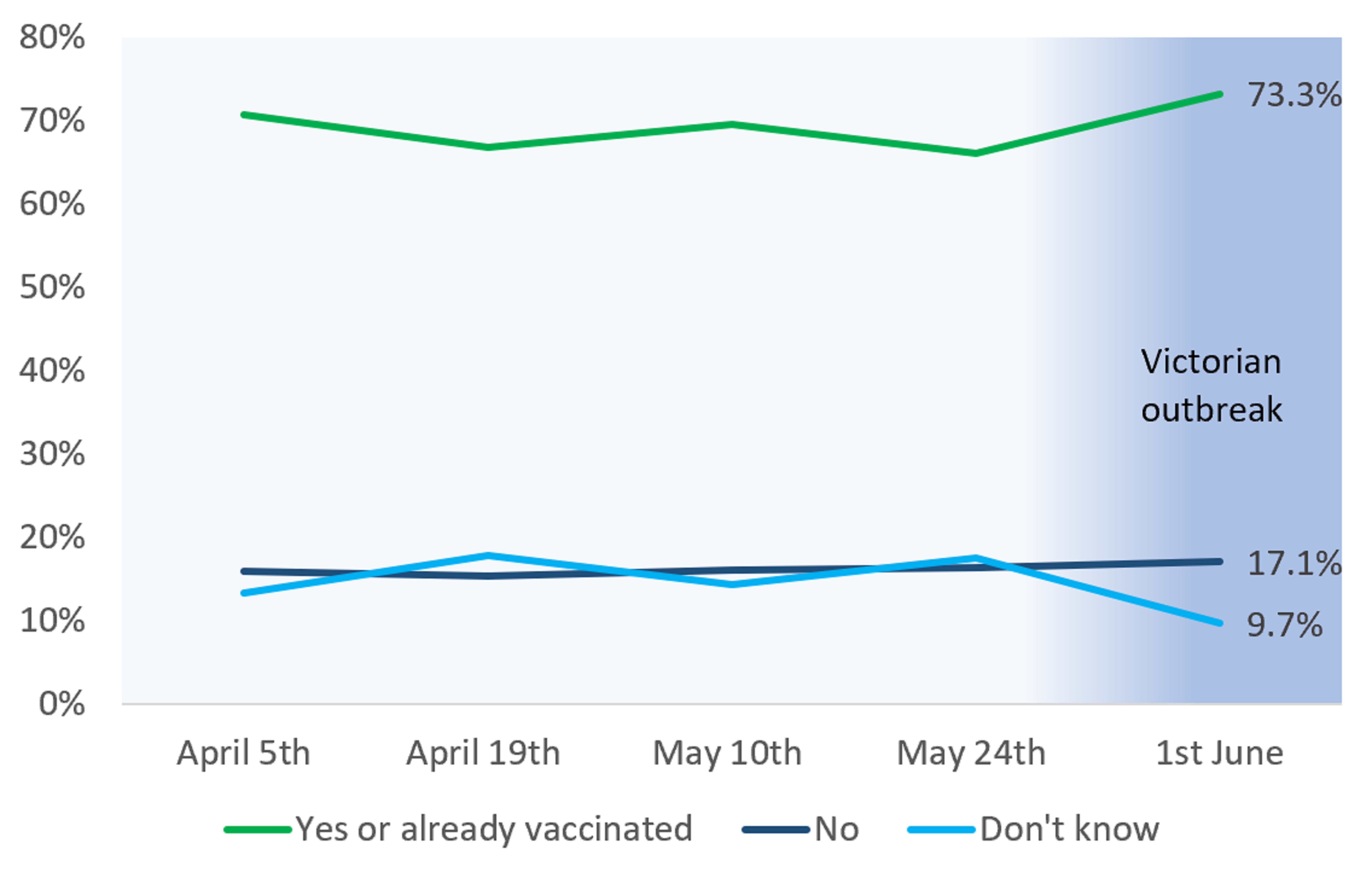

The proportion of Victorians willing to be vaccinated (including those who had already had the vaccine) in the week before the outbreak was 66 per cent, and this increased to 73 per cent in the first week of lockdown (Figure 2).

In the rest of Australia, this increased from 66 per cent to 69 per cent. Since February, on average, Victorians have been slightly more willing to be vaccinated than the rest of the country.

Our data also captures those who said they are not willing to be vaccinated and those who are still unsure.

The proportion of Victorians who said they are not sure about being vaccinated was 17 per cent just before the Victorian lockdown and fell to 10 per cent in the first week of lockdown (Figure 2).

But, despite the Victorian outbreak, vaccine hesitancy remains high – and in order to achieve herd immunity, around 60 and 70 per cent of our population would need to be protected against COVID-19.

The proportion of Victorians who said they are not willing to be vaccinated has been slightly higher in Victoria compared to the rest of Australia.

Health & Medicine

Getting a COVID jab is safer than taking aspirin

The proportion unwilling to be vaccinated has been slowly increasing in Victoria, even after the Victorian outbreak, and was 17 per cent in the first week of June (Figure 2).

However, in the rest of Australia, the percentage of those who do not want to be vaccinated fell from 19.5 per cent to 15.9 per cent in the first week of June.

For those adults who have not yet been vaccinated but want to be, only 19.3 per cent would be willing to have any type of vaccine.

Of the 80.7 per cent of this group who expressed a preference for a specific type, 77.9 per cent prefer Pfizer, 15.5 per cent prefer AstraZeneca and 6.5 per cent prefer Moderna.

It remains unclear the extent to which those 50 years old and over, who could at the time of the survey only get AstraZeneca, would accept AstraZeneca even if they prefer Pfizer.

But this preference for Pfizer will likely get stronger across all age groups following the new recommendation that only people over 60 get the AstraZeneca jab, and despite the fact that medical experts in Australia say they can easily detect and treat the blood clots.

Health & Medicine

Should we pay Australians to get vaccinated?

Unless vaccine eligibility changes, these numbers suggest securing a higher supply of the Pfizer vaccine (and potentially other vaccines) could speed up Australia’s vaccination rollout.

Those already vaccinated had a weaker preference for Pfizer compared to those who have not yet been vaccinated. This suggests that many people were happy to receive AstraZeneca as that is all they were offered, even though they would have preferred Pfizer.

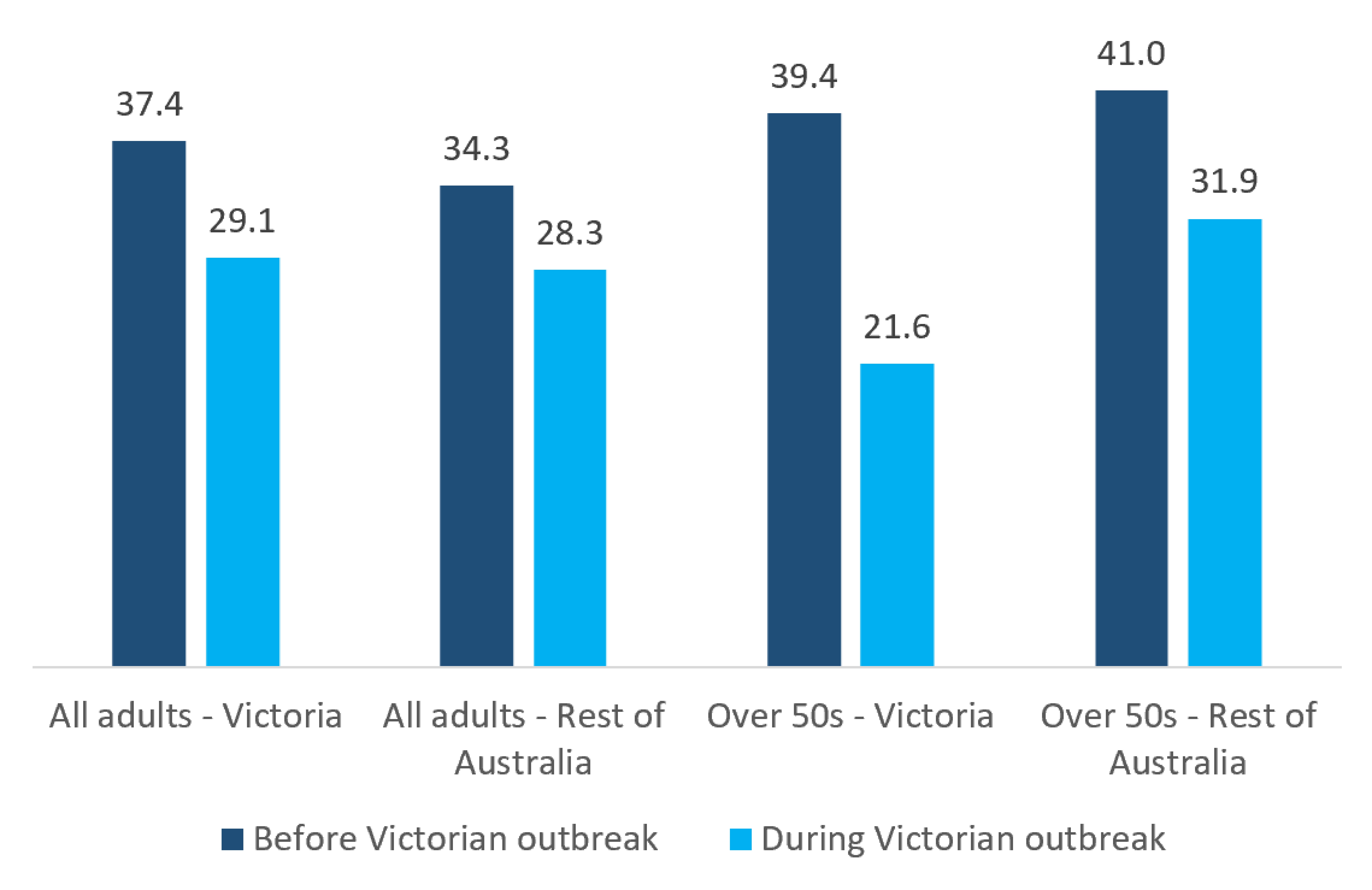

In Victoria, before the outbreak, almost 37.4 per cent of people were willing to wait to get vaccinated (39.4 per cent for those aged over 50 years old).

During the first week of the outbreak, the percentage willing to wait in Victoria dropped sharply by 8.3 percentage points (from 37.4 per cent to 29.1 per cent) for all adults, and by a very large 17.8 percentage points (from 39.4 per cent to 21.6 per cent) for those aged over 50 years old.

More people in Victoria now want the vaccine.

Impatience to get vaccinated has also increased in the rest of Australia before and after the Victorian outbreak, but not as much as in Victoria.

Health & Medicine

Learning as we go during vaccine rollout

For all Australian adults, the proportion willing to wait fell by six percentage points, from 34.3 per cent to 28.3 per cent. This fall was slightly higher for those 50 years old and over, by 9.1 percentage points from 41 per cent to 31.9 per cent.

While the outbreak in Victoria seems to have persuaded many Victorians who were unsure about vaccination, the stubbornly high vaccine hesitancy is concerning.

It reflects an urgent need for a more effective and better-coordinated vaccination strategy at all levels of government.

Unfortunately, an effective campaign like this still seems out of reach with ongoing problems with supply and an increasingly dysfunctional relationship between the Commonwealth and States and Territories, with the blame game in full flight and divided responsibilities leading to further delays and confusion.

The strength of the preference against AstraZeneca is over-inflated relative to the actual very small risks of rare blood clots.

But much of this negative sentiment can be traced back to government’s complacency in encouraging vaccination, its decision to rely largely on one vaccine, and an apparent lack of a well thought through and evidence-based public education campaign.

Health & Medicine

What chickens can tell us about living with COVID-19

Correcting these policy failures is crucial for getting to a truly COVID-safe Australia as soon as possible.

The recent Victorian outbreak has shown, once again, that governments have not been prepared for the vaccine rollout. And even though we were warned by government medical advisors that outbreaks can and will happen anytime, we remain underprepared.

Governments need to build on people’s willingness to get vaccinated, while also using behavioural economics principles to nudge people. Persuading those who persistently refuse to get vaccinated must be part of a longer-term strategy.

In the meantime, the cost of prevailing low vaccination rates becomes increasingly large when outbreaks occur and we end up in lockdown…again.

Banner: Getty Images