Politics & Society

How the toxic went mainstream

Neo-Nazis feed on fear and controversy. Their response to new Australian laws banning their symbols is hard to predict

Published 4 December 2023

Last month, Victoria passed laws making it illegal to perform the Nazi salute. Under the new laws, anyone who displays or performs a Nazi symbol or gesture in public will face penalties of up to $AU23,000, 12 months’ jail or both.

On 28 November, the Federal Government signalled its intention to introduce similar laws nationwide.

But how effective and enforceable are these kinds of laws?

Unfortunately, we may soon have an answer to ‘how enforceable’ after a Melbourne man became the first person charged under the new legislation on 10 November. It is alleged he performed the salute as he left a Melbourne court at the conclusion of another legal proceeding.

Questions of legality aside, in looking at how effective the law may be, we need to consider the potential consequences – including unintended consequences – of banning specific symbols and gestures.

If the salute itself is merely a symptom of underlying neo-Nazism and white supremacy, what is the political utility of banning it?

Politics & Society

How the toxic went mainstream

To begin, it is worth exploring how and why neo-Nazi groups employ these gestures and symbols in the first place, and to what end.

Neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups rely heavily on a wide array of symbolism and imagery. In particular, they draw on Nazi iconography, like the salute, swastika (which is also known as the Hakenkreuz) and other symbols, like the well-known ‘SS’ symbol.

Contemporary neo-Nazi groups draw on these symbols for a variety of reasons, including for recruitment materials, and to disseminate political and ideological messages both online and in the streets.

Neo-Nazis employ symbolism during events and rallies to help members identify and connect with one another. They may also use flags and other insignia as face coverings to anonymise their identities while simultaneously broadcasting their group membership.

All these symbolic practices work to instil fear in the people and groups neo-Nazis target.

The ban on the Nazi salute and symbols is an attempt to disrupt these strategies and tactics – not only their use in racially motivated attacks, but so too the wider organisational purposes for which they are deployed.

Although this may seem like a logical step, it is worth considering how neo-Nazi groups might respond and adapt to the new bans.

From my experience researching white nationalist and white supremacist groups in Australia, I think a combination of responses is likely.

Importantly, none of these responses precludes the others and specific people or groups may draw on multiple strategies – either simultaneously or at different times.

Health & Medicine

Why are we so vulnerable to bad information?

There is a strong possibility neo-Nazi groups will adapt the symbols they draw upon to circumvent the ban while still demonstrating their adherence to white supremacy. They could effectively adapt the symbolism they use to ‘hide in plain sight’.

There is a long history of white supremacist groups employing this strategy.

For example, members of neo-Nazi groups often adorn their clothing, flags and banners with the numbers ‘14’ or ‘88’ (and sometimes ‘1488’). Here, 14 stands for the famous 14-word white supremacist slogan, “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children”, while 88 stands for “Heil Hitler” (because H is the 8th letter of the alphabet).

Another prominent example includes the use of the ‘okay’ hand symbol or emoji which white supremacists claim resembles the letters ‘W’ and ‘P’, which stands for ‘White Power’.

If a prosecution was brought for using one of these ‘surrogate symbols’ it would be up to the courts to decide if they constitute a crime under the new law.

Across Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and Cananda, white nationalists frequently use ‘unbannable’ flags to publicly demonstrate their commitment to white supremacy. For example, the Australian and Canadian Red Ensign flags have been appropriated as symbols of white supremacy.

This is because the Canadian Red Ensign “reflects a time when Canada was a lot whiter”, while the Australian Red Ensign, though still used for shipping, was more widely in use during the time of the White Australia policy.

These groups also fly the national flag upside down.

Health & Medicine

Sorting fact from fiction in a post-truth world

This has been used at innumerable far-right protests – including during the Freedom Convoy protests that occurred throughout the COVID-19 pandemic; the Unite the Right protest in Charlottesville and the Capitol Hill Riots on 6 January 2021.

This practice is used by white supremacists to signify their belief that the nation is under attack, via the so-called ‘Great Replacement’ (of white people), or ‘White Genocide’.

The ban on the Nazi salute, along with subsequent legal proceedings, has the potential to reinforce prevalent neo-Nazi beliefs about being persecuted and targeted by government and society.

While this targeting is to some extent true – because after all, neo-Nazis are specifically targeted by the new laws – we should be mindful that bans on specific gestures and symbols may reinforce and seem to substantiate these convictions, potentially leading to a reactionary response, like a greater commitment to the neo-Nazi cause by new or existing members.

This doesn’t mean that laws like this shouldn’t exist – it does mean that we need to be aware of the potential reaction.

The final possibility I want to mention is that for some neo-Nazi members, the new bans and subsequent legal proceedings may intensify the significance of the salute.

This is because its newly established illegality will solidify any feelings of persecution, as I’ve mentioned above, while also providing a means for members to demonstrate the intensity of their commitment to their cause.

Perversely, this combination could lead to an increase in public performances of the gesture, which, although always notable, will now almost guarantee an immediate response from law enforcement and the attention that comes with that.

Given we already know Australian neo-Nazi groups are populated by a relatively small number of extremely active individuals, who relish media attention, this does not appear to be an unlikely outcome.

Politics & Society

How disinformation is undermining our cities

Neo-Nazi and white nationalist groups rely strongly on symbolism and imagery to further their cause – whether that’s recruiting, messaging or for carrying out violence.

Banning the salute is likely to have a range of effects on the way neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups operate.

While these considerations are not an argument against the bans, they highlight the need to monitor and review their effectiveness.

Aside from these potential consequences, a crucial point to consider is that banning the salute addresses only one small symptom or manifestation of white supremacy.

It does nothing to address the underlying social, political, and cultural conditions that embolden neo-Nazis.

By focusing on the salute as if it were a discrete action that can be isolated, the ban could arguably serve to divorce the gesture from the conditions that enable it – many of which implicate mainstream society.

Understood in this way, banning the gesture is itself a political gesture with political utility.

While it ostensibly adds to the antiracist credentials of those who devised and now enforce it, the ‘simple’ solution of criminalisation may prevent more genuine efforts towards antiracism.

White supremacy and white nationalist movements are a pervasive and seemingly intractable problem.

Given what we know about how these groups operate, we should be mindful of the potential consequences – including those which are unintended – that new laws banning specific symbols and gestures might have.

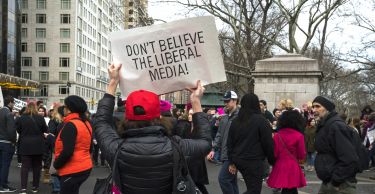

Banner: An anti-immigration rally in Melbourne, Australia in May 2023. Getty Images.