Business & Economics

Why South Korea’s fresh start is good news for Australian business

By 2030, two-thirds of the world’s middle class will live in Asia and Australian business leaders have a lot of work to do to become Asia-capable in the 21st century

Published 6 October 2017

Globalisation, digitisation and disruption are quickly changing not only the way we work, but also the work we do – as Australia looks to deepen its engagement with the powerhouse economies to its near north.

With the country’s economic focus tilting firmly towards Asia, our professionals of the future are being challenged to embrace a global mindset and to develop intercultural understanding.

Which will be crucial, as by 2030, two-thirds of the global middle class, or 3.2 billion people, will live in Asia.

A recent report produced by Asialink Business at the University of Melbourne, along with Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC) and the Institute of Managers and Leaders, suggests there is a lot of work to be done.

Match Fit: Shaping Asia Capable Leaders found that despite the familiar rhetoric about the importance of Asia to Australia’s economic future, “many of our nation’s top business leaders are yet to take seriously the need to build knowledge and skill in doing business” with Asia.

The report’s authors examined the boards and senior management teams of the ASX 200, as well as Australia’s top 30 private companies, against six capabilities: sophisticated knowledge of Asian markets, extensive experience operating in Asia, long-term trusted relationships in the region, capacity to deal with government, a useful level of language proficiency and, most importantly, an ability to adapt one’s behaviour to Asian cultural contexts.

Their assessment is bleak, with nine in 10 publicly listed companies deemed not fully “Asia-ready”. And 80 per cent of private businesses were similarly under-prepared.

Interestingly, the report also found that executives in privately-owned companies were 10 times more likely to speak an Asian language, while women executives in the ASX 200 were at least four times more likely than their male counterparts to demonstrate a capacity to engage with Asia.

Business & Economics

Why South Korea’s fresh start is good news for Australian business

Louise Dunn, the Director of Capability Development at Asialink Business, says it is important Australian businesses wishing to expand into Asia appreciate that building relationships with Asian partners over the long term is crucial to their likelihood of success.

“Australians often have a very different sense of time,” she says. “We tend to be task oriented and not relationship oriented.”

Ms Dunn says these differences can be overcome by learning to reflect on our own behaviour.

One of the points the Match Fit report stresses is that Asia is not homogenous but made up of different cultures. Additionally, Asia capabilities are not natural talents, but ones that can be learned through training, experience and access to practical research.

Ms Dunn says the first step for individuals wishing to do business in the region is developing their “cultural intelligence”. This means individuals becoming more aware of their personal style and understanding how to adapt to Asia’s diverse cultures. The Australian way of doing business, for example, our tendency towards direct communication, is not the only way, she adds .

It’s this cultural intelligence that maximises the chance of business success in Asia for those individuals and organisations who take the time to build it. They are better able to understand how their own workplace style is likely to be interpreted by others, and put strategies in place to build trust and effectiveness in working with colleagues, clients and cultures in the region.

And it’s these cultural intelligence skills that will be more important in the workplaces of the future.

According to the report Australia’s Jobs Future, the rise of Asia and the services opportunity, published by Asialink Business, PwC and ANZ – it’s services that have the potential to become Australia’s number one export to Asia by 2030. These are areas supporting one million Australian jobs in education, transport, health, tourism, financial services and business services.

The sector is already a crucial, if under-recognised, source of export income. The report says that in 2013 services accounted for 41 per cent of Australia’s value-added export earnings, compared to 37 per cent for mining and 23 per cent for agriculture and manufacturing combined.

At the same time, services made up 34 per cent of our exports to Asia, compared to 54 per cent to the rest of the world (chiefly New Zealand, the US and the European Union).

Australia can take advantage of this historic opportunity, but is likely to face stiff competition from rising Asian competitors.

And according to Louise Dunn, this shift requires government, business, and the education sector to work together to develop an Asia-capable workforce.

“Asia’s demand for world-class services is growing, but it does not automatically flow that Australia will increase its share of the pie; Australian businesses will need to increase their presence on the ground in Asia, and hone their skills in building long-term, sustainable relationships with Asian business counterparts.”

Professor Anthony D’Costa, the chairman of Contemporary Indian Studies at the University of Melbourne, gives a striking example of the scale of competition Australians are likely to face.

The rise of an educated Indian middle class, and a globalised economy, will mean that Australian professionals will find themselves competing with Indian professionals with the same level of education and skill.

Take engineers, for example – India produces 800,000 graduates each year. In 10 years, that will mean around 8 million qualified engineers are in the market. Even if you only take the top half, that is four million engineers.

Politics & Society

Is Australia becoming the ‘lonely’ country?

“Can the best in Australia compete with the best in India?” Professor D’Costa asks. “It is a new kind of competition they will have to face, that they are now not facing. You will have a new ecosystem for the professional classes.”

That fast-looming global reality is a focus for educators and industry alike, says Ms Dunne.

“There is no doubt the workforce of the future will be deeply interconnected. Asia and Australia will need to compete to succeed in highly competitive global markets – business, industry and educators alike need to urgently get match fit.”

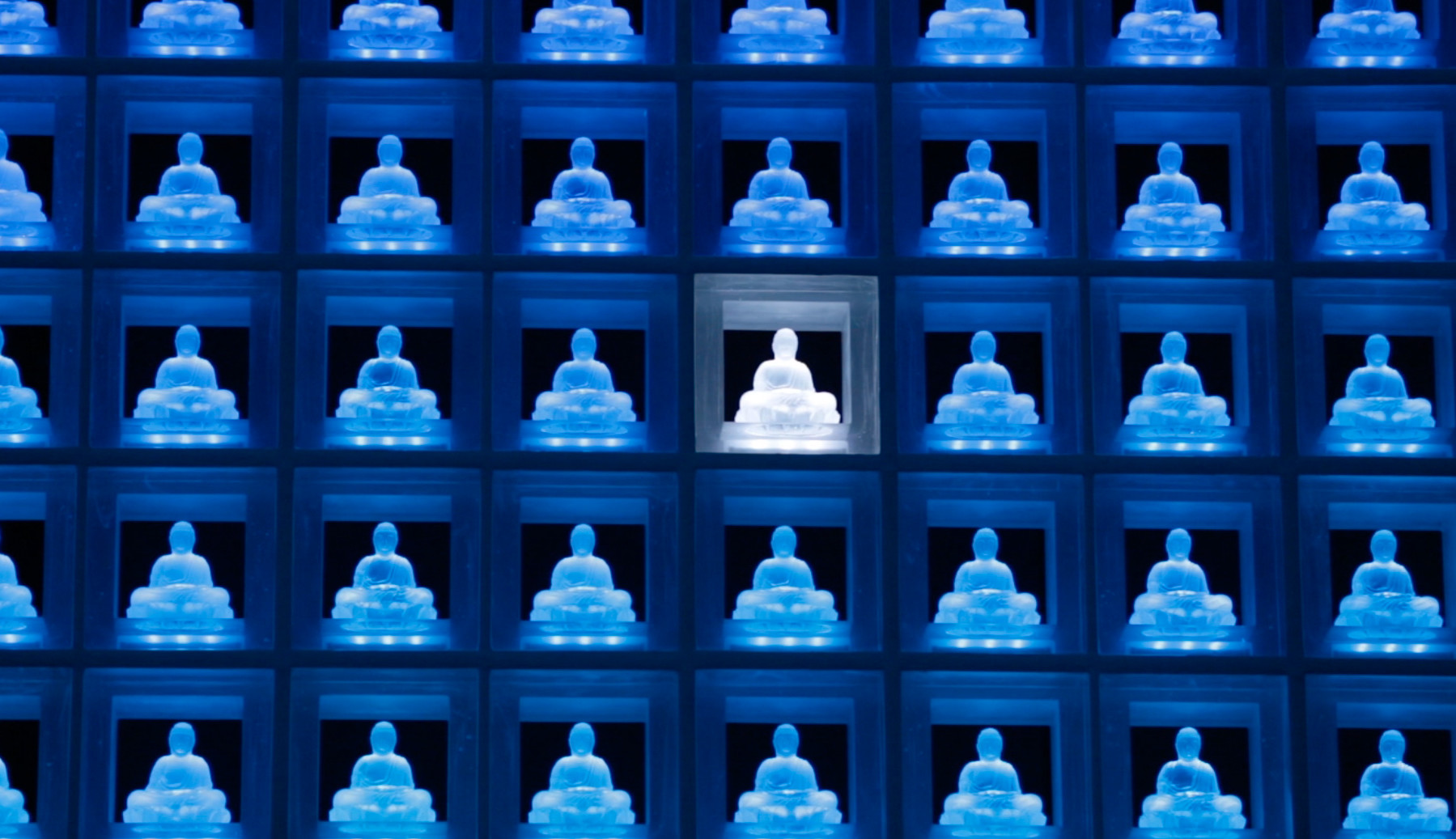

Banner image and video: Getty Images