Health & Medicine

Outsmarting Zika and Dengue Fever

The Zika emergency seemed to come from nowhere, but there are a host of other viruses making scientists nervous

Published 5 February 2016

The 2015-2016 Zika outbreak in Latin America infected millions, sparking a global public health emergency. To many people, it seemed to come out of nowhere.

But while Zika poses a global health challenge, there are more where Zika came from that could blindside us.

Few people had heard of Zika before early 2016, when the US issued a travel warning in response to growing suspicions that the mosquito-borne virus was the culprit behind a worrying rise in reported cases in Brazil of the brain birth defect – microcephaly.

But as the human population increasingly intrudes into animal habitats, coming into contact with new bugs hosted by the likes of bats and birds, the risk of transmission is growing.

At the same time, increased mobility is increasing the potential for any outbreaks to rapidly spread.

Health & Medicine

Outsmarting Zika and Dengue Fever

We asked the Professor Cameron Simmons and Associate Professor Jason Mackenzie at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity – what are some of the other viruses and critters out there that have authorities nervous?

Named after the Malaysian village where it was discovered in 1998, the Nipah virus causes flu-like symptoms and is carried by fruit bats. It is passed to humans through contact with infected pigs.

By 2016, there were 477 recorded infections but the mortality rate is high at just over 50 per cent, which has resulted in 252 deaths since 1998.

Even more worryingly, since 2001, there has been growing evidence of human-to-human transmission.

“Bats can harbour hundreds of viruses, many of which can affect humans, but we don’t understand a lot about how the transmission occurs,” says Associate Professor Mackenzie, from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

“Nipah is a very serious issue.”

In Bangladesh and India, there have been outbreaks caused by people drinking raw date palm sap infected by bats urinating in the sap as it was collecting.

Strong evidence has also that the virus can be transmitted from human-to-human contact.

Currently, there is no vaccine for Nipah.

Health & Medicine

Testing wildlife could stop pandemics in their tracks

MERS is related to SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) that broke out originally in China in 2002 and caused a worldwide panic before it was contained.

Fortunately, unlike SARS, which can be readily transmitted among humans, it is difficult for MERS to spread from person to person - at least for now.

“What worries us is that the virus will mutate and evolve an ability to transmit easily between people.

“So far it has required very close contact with someone severely sick with this virus to have a chance of getting infected,” says Professor Simmons, also from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

In 2016, there have been 1,626 laboratory confirmed cases of which 586 died, making that a fatality rate of 36 per cent. All cases have been linked to the Middle East with those outside the area linked to travel in the region, or contact with recent travellers.

More than 80 per cent of cases have been reported from or linked to Saudi Arabia.

During the SARS outbreak from November 2002 to July 2003 – 8,098 people fell sick of which 774 died.

Health & Medicine

Bird flu, human cases and the risk to Australia

Another potential candidate for a potential outbreak of a new respiratory disease is the Avian Influenza virus called H7N9.

First reported in China in 2013, there have been 667 reported cases of H7N9 and 229 deaths up to October 2015.

Infections have been largely limited to China and mostly to elderly men who had direct exposure to live poultry at markets and farms.

“This is another on the radar that makes us nervous, particularly about it evolving into a virus that jumps easily from human to human,” said Professor Simmons.

“So far, there is no really good evidence that that this virus is fit for that.”

The most well-known bird flu that has crossed into humans is the H5N1 strain.

This strain first infected a human in Hong Kong in 1997 and has a mortality rate of a worryingly high 60 per cent.

Transmission to humans is difficult and has been linked to the consumption of infected raw poultry and contaminated poultry blood, but there is evidence of limited person-to-person transmission that appears to require close contact over long periods.

Between 2003 and 2015, there were 846 recorded cases of H5N1 resulting in 449 deaths. The largest number of deaths were in Indonesia at 167 and Egypt at 116.

Health & Medicine

Tracking avian influenza to safeguard Australia

“It is these respiratory viruses that can go from human to human that are of greater concern than viruses that require a mosquito in the middle, because the epidemic potential is much greater.

“They can infect a lot more people more quickly, and often they have high case mortality rates. That is why we worry,” says Professor Simmons.

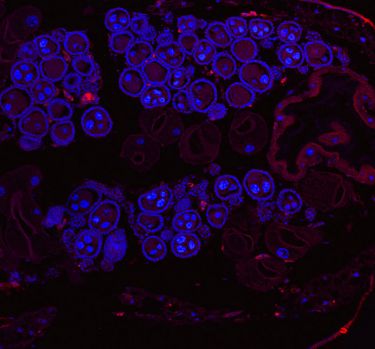

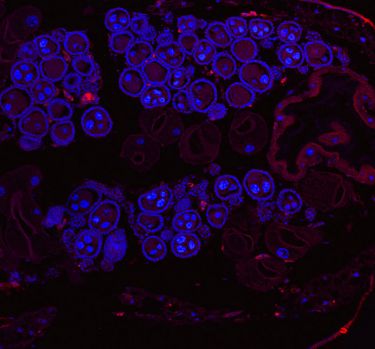

The Norovirus, or gastric flu, can knock you off our feet for days, causing vomiting, diarrhoea and stomach pain.

It is spread through contaminated food and commonly infects about 10 per cent of the world’s population every year.

For the children, the elderly and the weak it can be fatal, resulting in about 200,000 death annually. Of these about 70,000 are children in the developing world.

Norovirus is commonly associated with 'close' environments like cruise ships or nursing homes where it can quickly spread.

Its impact, while short lived, can be debilitating and for that reason the US rates it a Class B bioterrorism agent.

The problem is, every few years, a particularly virulent strain breaks out leading to a spike in infections. And Associate Professor Mackenzie says trying to develop a vaccine is proving extremely difficult.

Health & Medicine

Vaccinating newborns against the deadly rotavirus

“Vaccine development and anti-viral therapy for Norovirus is almost non-existent. It changes rapidly and every three-to-five years there is a strain that will spread across the planet causing pandemic infections,” Associate Professor Mackenzie says.

Despite efforts of modern science researchers have so far been unable to grow the virus in the laboratory, seriously handicapping efforts to develop a vaccine or drug treatments.

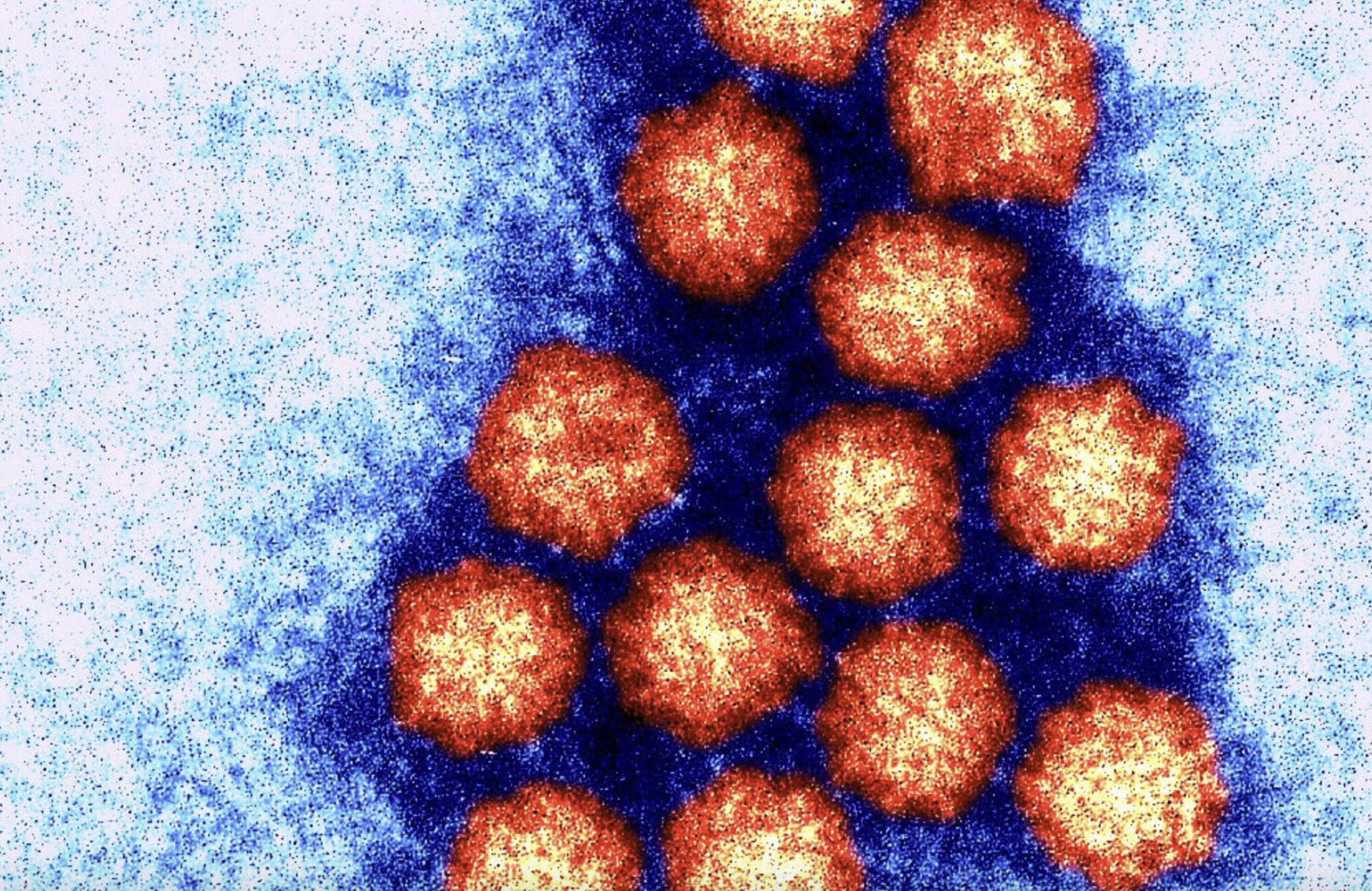

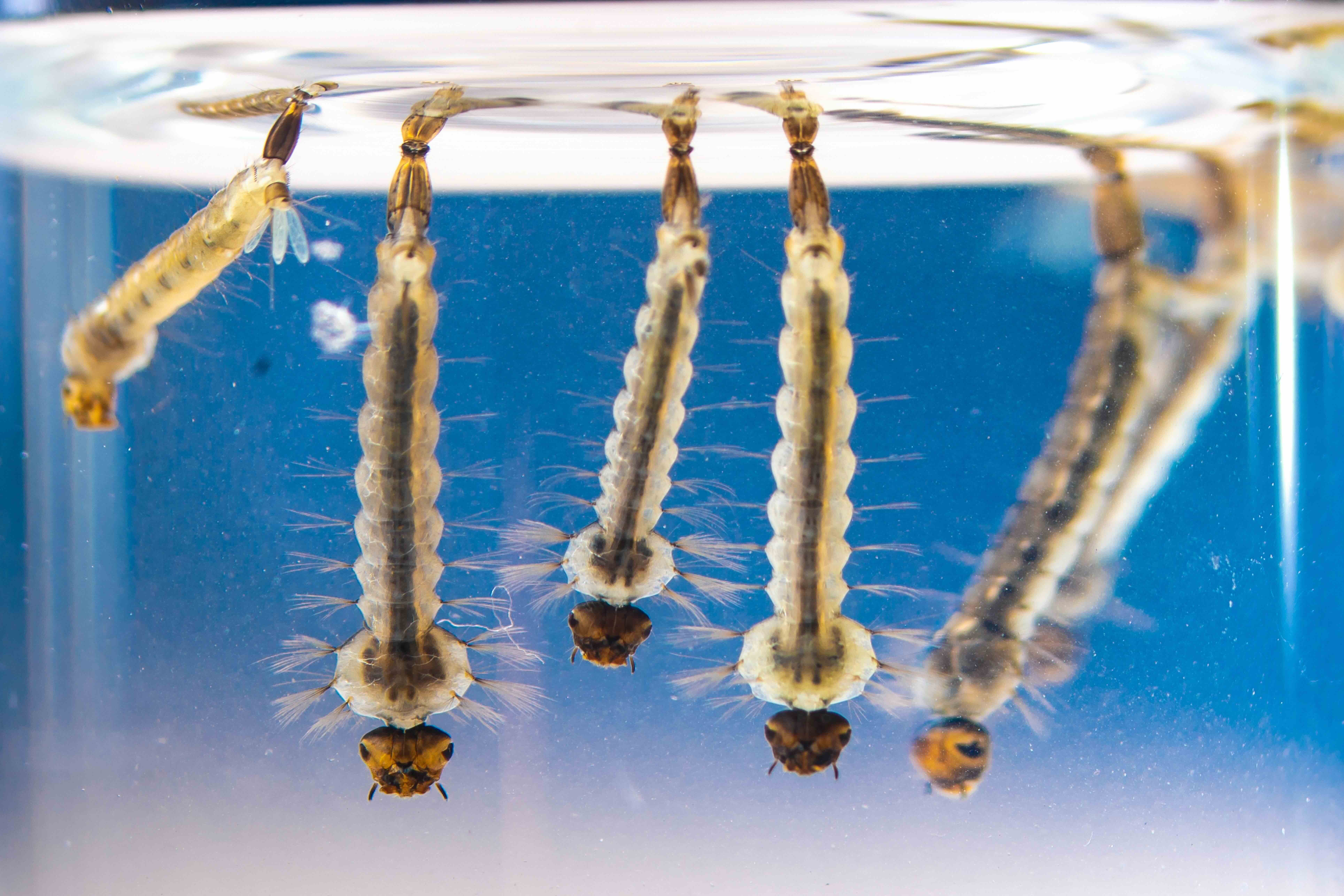

Aedes albopictus isn’t a virus, it’s a mosquito that could bring a virus to a place near you.

The geographic spread of the Zika virus has been limited by the restricted range of the Aedes aegypti mosquito that is the main transmitter of viruses such as Zika, Dengue Fever and Chikungunya.

But Professor Simmons says another mosquito has emerged as a carrier in more temperate areas such as southern Europe and the US.

While Aedes aegypti can survive mainly in only tropical climes, its cousin Aedes albopictus, commonly called the Asia Tiger Mosquito, can better survive winter months and is one of the fastest spreading species on the planet.

The spread of Aedes albopictus is a problem because it can also transmit the Dengue and Zika viruses.

“Wherever Aedes Albopictus is are the same locations where Dengue, or Chikungunya or Zika could be transmitted,” says Professor Simmons.

Sciences & Technology

Tracking the movement of mosquito stowaways

Associate professor Mackenzie says concerns about the increasing spread of mosquitoes weren’t limited to Aedes albopictus given growing worries that global warming will increase the range of virus-carrying mosquitoes.

“Mosquito-borne viruses like Zika, West Nile, Dengue and Chikungunya have emerging potential because if you change the distribution of the vector a greater amount of the population can now be exposed to that virus and many of them are highly pathogenic.

“So there are a lot of people who are concerned about how the climate is affecting vector distribution and exposing humanity to these new viruses. That is a big concern at the moment,” says Associate Professor Mackenzie.

When New York was first hit by the mosquito-borne West Nile Virus in 1999, it quickly spread and has now established itself across the US. it is estimated to have cost the country $US778 million.

While most people struck the virus have no symptoms or suffer only temporary fever, aches and vomiting, in one in 150 cases a serious neurological illness results – like encephalitis or meningitis that can be fatal.

The increasing range of mosquitos presents the unsettling prospect of scientists discovering that viruses once thought to have only temporary symptoms could be more invidious if let loose on a larger population.

This is exactly what has happened with Zika.

Professor Simmons says the suspected link between Zika and microcephaly has only emerged because of the massive spread of the disease once it hit a new population, creating the critical mass to make such a link noticeable.

Sciences & Technology

Dengue-blocking mosquitoes here to stay

As Professor Simmons says, “it's a numbers game,” which isn’t a particularly comforting thought".

The comforting thing however is that thanks to improved scientific detection and surveillance we actually know about these threats to global health and can prepare as best we can.

“We now spend our time worrying about a whole lot more things than 20 years ago, but you’d rather know than not know,” says Professor Simmons.