Health & Medicine

Schizophrenia: Mapping how the brain changes

Neuroscientists have shown the brain’s white matter develops slower in young people at high clinical risk of a psychotic episode, which may pave the way for earlier treatment

Published 24 May 2021

As early as age 12, some young people are classified as being at high clinical risk of developing psychosis.

The effects of psychosis can include mild delusions, hallucinations, and disorganised speech and the effects can impact on a person’s ability to function in everyday life. A young person is classified as high risk if they meet certain criteria including the presence of mild psychotic symptoms accompanied by a decline in day-to-day functioning.

This classification doesn’t mean that a person will go onto develop a psychotic condition such as schizophrenia, but around 10-35 per cent do.

To identify young people most at risk of psychosis, and as early as possible, researchers and clinicians want to understand if there are brain changes that can be observed before a psychotic episode occurs.

Health & Medicine

Schizophrenia: Mapping how the brain changes

The human brain is divided into grey and white matter. Grey matter is composed mainly of cells that process information (the neurons), and white matter is found deeper in the brain and enables the transfer of this information via nerve fibres known as axons.

Previous studies have shown that grey matter volume and thickness rapidly decline in the first two years following the transition to psychosis, before then plateauing. These findings suggest the onset of psychosis is a dynamic event in the neurobiology of the brain, resulting in changes to grey matter.

However, it is unclear whether white matter alterations follow the same course – a rapid change in white matter structure co-occurring with a transition to psychosis. A breakdown in white matter architecture can disrupt healthy communication within and between brain regions, making it crucial to pinpoint when white matter changes first appear.

To understand more, our team of neuroscientists across the University of Melbourne and Harvard Medical School is studying whether brain white matter abnormalities appear in all people at risk of psychosis or just in those who go on to develop a fully-fledged psychotic disorder like schizophrenia.

Health & Medicine

Mapping how schizophrenia changes brains

Our research published in Molecular Psychiatry supports the former view – that brain abnormalities ensue regardless of a transition to a psychotic disorder.

We monitored brain development patterns across 230 individuals at high clinical risk of developing psychosis and 56 healthy individuals, nested within the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS).

NAPLS is the largest multi-site neuroimaging study of individuals meeting criteria for high clinical risk of psychosis. Participants underwent several magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans over the course of one year and we analysed their brain white matter throughout this time.

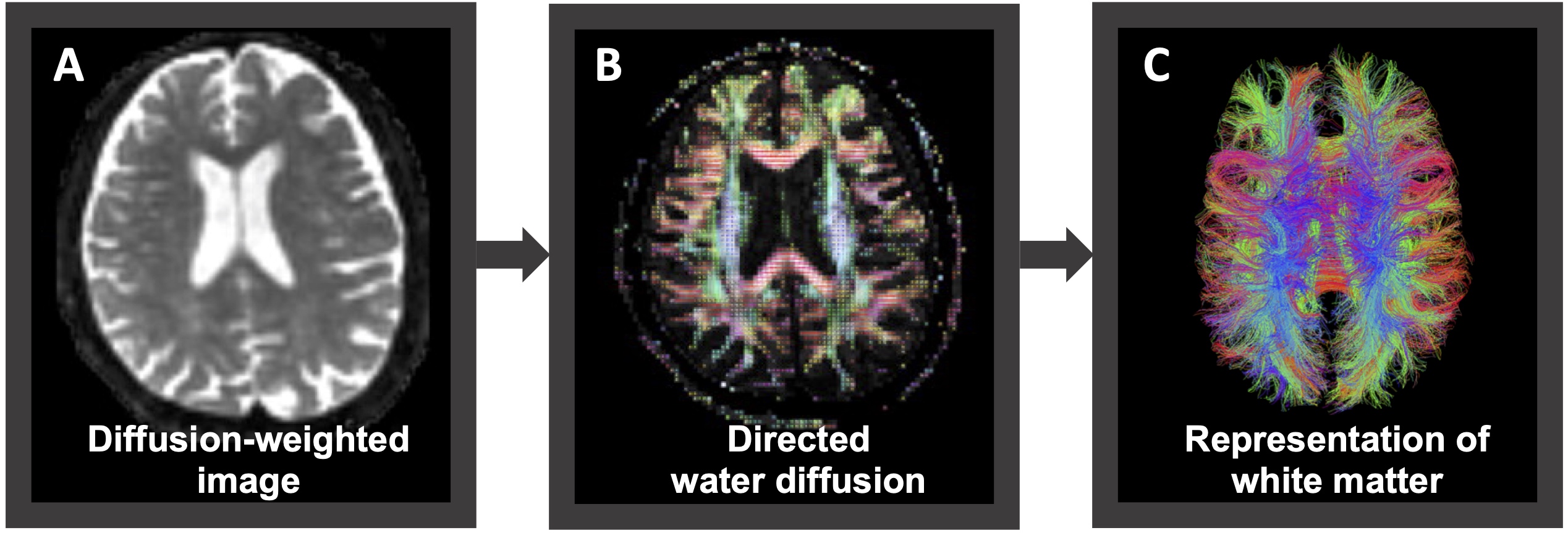

To do this, we used a specific MRI method called diffusion-weighted imaging. This technique measures the diffusion of water molecules to generate contrast in brain images.

Because water diffusion in the brain is hindered by cellular structures and travels faster along the grain of fibres (compared to across fibres), diffusion patterns can reveal details about the architecture of tissue, particularly in the brain’s white matter.

Typical white matter development extends through to middle adulthood and is characterised by a pruning and strengthening of the brain’s connections – white matter – to help regulate electrical activity in the brain.

Health & Medicine

The brain benefits of music

Our study indicates that white matter develops at slower rates in people at risk of psychosis compared to healthy controls – that is people who haven’t been classified at higher risk.

This perturbed pattern of brain development in white matter structures was found in the clinical high-risk group, regardless of whether or not individuals transitioned to a fully-fledged psychotic disorder. These findings suggest that measures of brain white matter deviate from healthy development prior to diagnosable psychotic illness.

As part of this study, we monitored a wide range of risk factors that may shape patterns of white matter development.

Intriguingly, the brain changes that we observed in people at risk of psychosis were linked to more severe psychosis symptoms such as unusual thought content and perceptual abnormalities, and to factors dating back to childhood, including poor adjustment to school life, scholastic performance and peer relationships.

These findings emphasise the need for holistic clinical approaches to support young people at high risk of psychosis, which target multiple dimensions of health during childhood and adolescent development.

Health & Medicine

Fear, memory and brain exploration

It is becoming clear that early interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy – implemented prior to established psychotic illness – are crucial to halt or even prevent the serious consequences of a fully-fledged psychotic illness. However, the picture is far from complete.

In ongoing work, we are working to solve an important outstanding question: can neuroimaging techniques help doctors determine who is more likely to progress to schizophrenia or other serious psychotic disorders?

We are actively researching this question which may assist doctors in selecting the right treatment plan for people at high clinical risk for psychosis.

If you or anyone you know needs help or support, Headspace provides free online information and resources about psychosis, as well as telephone support and counselling to young people aged 12 to 25, and their families and friends.

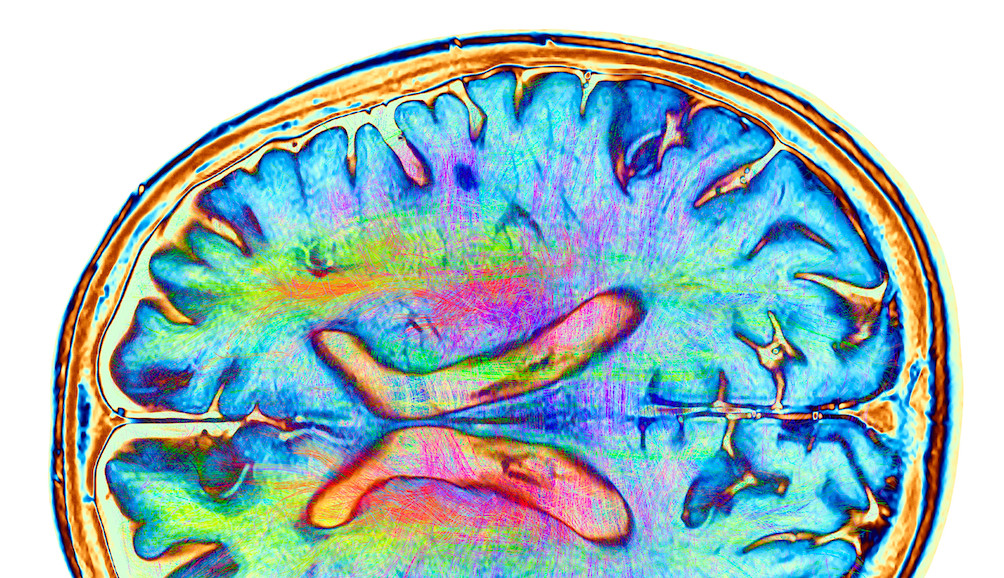

Banner: Computer artwork of a MRI top view of the brain showing white matter fibres/ Getty Images