Politics & Society

The West’s age of retreat

Years of turmoil and a chaotic campaign period mean the South American country’s political future is uncertain

Published 27 September 2018

Brazilians head to the polls on 7 October for a general election unlike any the country has ever seen.

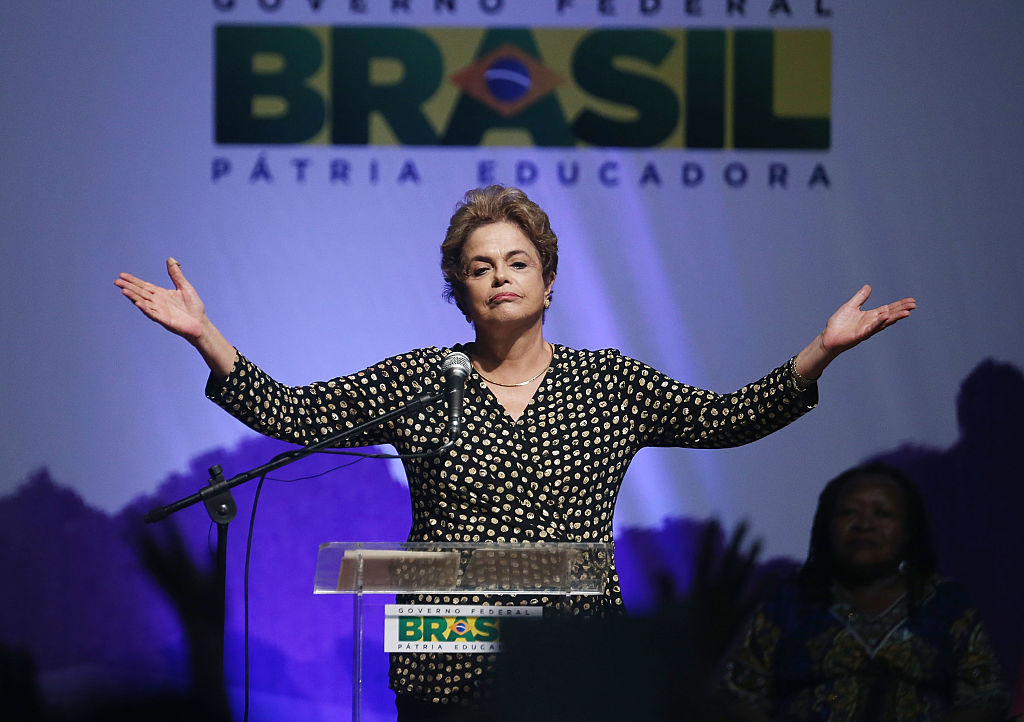

This is the first election since the 2016 impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff and the outcome, along with perhaps the future stability of Brazil’s democracy, is entirely unpredictable.

At stake in the Portuguese-speaking federal republic of over 210 million people is:

The Presidency (a four-year term, with re-election to a second term possible)

The entire lower house (the 513-member Chamber of Deputies)

Two-thirds of the upper house (the 81-member Senate)

State governorships and legislative houses.

Voting is compulsory, but a high abstention rate is expected after four years of turmoil and a chaotic campaign period.

Politics & Society

The West’s age of retreat

The background to these elections is the so-called ‘soft coup’ in August 2016 that ousted President Dilma Rousseff from the Worker’s Party (PT) - that elevated her coalition partner and Vice President Michel Temer from the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB) to the Presidency.

The justification to impeach President Rousseff was controversial and some considered it an attempt to end corruption investigations that had ensnared powerful members of Brazil’s political class.

Since assuming office, President Temer has departed from the Worker’s Party platform and tried to implement an aggressive neoliberal agenda. He has pushed through labour reforms that slashed workers’ rights and a constitutional amendment freezing government spending on health care, education and welfare for the next twenty years.

Due to his controversial rise to the Presidency and his deeply resented austerity measures, President Temer’s government is the most unpopular since Brazil’s return to democracy in 1985, with 82 per cent of the population rating it as “very bad” or “bad”.

In addition to political chaos, Brazil is facing several crises including the biggest economic recession in its history, rising unemployment, extreme inequality, one of the highest murder rates in the world (63,880 homicides in 2017), as well as noticeable increases in homelessness, hunger, and poverty.

Popular unrest has been recurrent. In late May, truck drivers went on a nationwide strike over fuel prices that ground the country to halt.

Unlike past presidential elections, which were largely dominated by coalitions led by the centre-left Worker’s Party (PT) and the centre-right Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), there is a large number of plausible contestants this year.

Leading the polls is Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party (PSL), a former military far-right congressman who has a reputation for making homophobic comments, claiming to be a crusader against communism, insulting women and minorities, as well as praising torturers and the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Politics & Society

Can Prime Minister Khan really deliver a ‘new’ Pakistan?

His platform includes combatting crime and recovering economic growth by weakening gun restrictions, militarising schools and privatising all state firms and utilities.

Although comparisons to Donald Trump are not uncommon, the more obvious parallel is to controversial Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and his brand of populist, misogynist and belligerent politics.

Bolsonaro was stabbed at a rally in early September and that could become a decisive factor in the upcoming election. He has gone through two surgeries and is expected to recover. The fact that he is now regularly in the news and can portray himself as a victim seems to have humanised him, bolstering his visibility and popularity.

He is likely to win the first round on October 7, and is in with a shot in the run-off to decide the presidency three weeks later.

One prominent candidate will not be on the ballot this October.

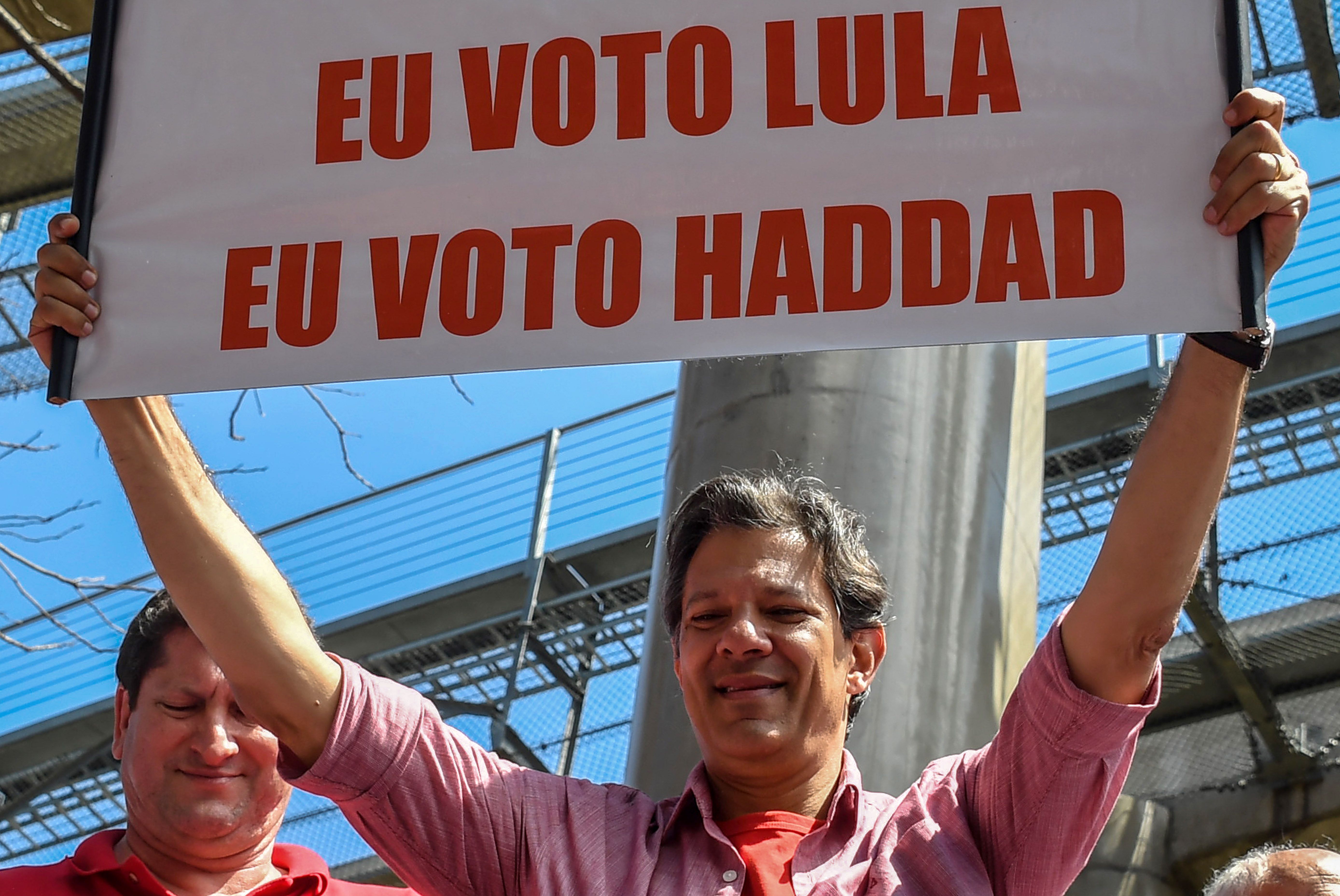

The still very popular former President Lula, who led the country between 2002 and 2010, was controversially imprisoned earlier this year and barred from running.

The Worker’s Party insisted on nominating him as a candidate until all judicial appeals were exhausted, which has given its current candidate, former mayor of São Paulo Fernando Haddad, little time to campaign.

The party will attempt to associate Haddad with Lula, who before being excluded from surveys was polling at 39 per cent per cent, despite being in prison – far higher than any other candidate.

As election day approaches, Haddad is expected to come second behind Bolsonaro, forcing a run-off between them on 28 October.

Close behind is Ciro Gomes, a centre-left developmentalist from the Democratic Labour Party (PDT), and Marina Silva, an environmentalist and former Worker’s Party Senator now in the Sustainability Party (REDE).

While Gomes has been able to attract left-leaning voters weary of the Worker’s Party - splitting the left - Silva has appealed to more liberal-leaning voters who do not sympathise with any of the major parties.

Politics & Society

Mexicans voted overwhelmingly for change. Will they get it?

Despite securing the support of a broad coalition of smaller parties and campaigning for longer periods than any other candidate on TV, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party’s Geraldo Alckmin has been lagging behind in the polls.

His sheer lack of charisma and his party’s association with Temer’s government have dismayed voters, making a showdown between the two major parties in the second round improbable.

Whoever wins the presidential election will have to build a workable coalition in Congress. Brazil’s convoluted system of coalition presidentialism, with 35 official political parties (26 of which are represented in Congress), means that no single party will come close to having a majority.

The future President will therefore have to come to agreement with a range of smaller parties for the government to be functional.

And it’s important that government functions well; it will face the highest inequality rates in the world, a tremendously unfair and regressive tax system, a number of deeply entrenched privileges for castes of the Judiciary, Legislative and Executive, and widening deficits despite deep cuts to welfare and public investment.

More than any other issue, however, it is democracy itself which is at stake in these elections.

The last four years of Brazilian politics have been marked by mounting polarisation, intolerance and unprecedented levels of violence since the return to democracy in the 1980s.

The assassination of LGBTQ people is at an all-time high and the murder of Marielle Franco, a vocal feminist and rising political leader of marginalised communities in Rio, remains unexplained.

The justice system is biased and the Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash), a vast probe into corruption at the state oil company, has thrown the impartiality of the Judiciary into doubt. Researchers and university professors have been targeted and subjected to persecution for their political views.

A run-off between Haddad and Bolsonaro could deepen the divide between those who want an electoral response to the 2016 parliamentary coup and those who have found an outlet for their frustrations, including with democracy, in the far-right Bolsonaro.

With Bolsonaro throwing the electoral process itself into doubt, showing little regard for human rights and with army generals, including his vice-presidential running mate, threatening military intervention - Brazilian democracy faces its biggest challenge in recent history.

Banner image: A pro-government rally organised by social movements, left-wing political parties and key workers’ unions voice their objection to calls for the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in Sao Paulo on August 20, 2015. Picture: Benjamin Tavener/Anadolu Agency/Getty Image