Health & Medicine

Predicting premmies: The test that could save babies’ lives

Bacteria in your mouth can wreak havoc in your body but research is on its way to developing a new vaccine, says Professor Eric Reynolds, winner of the 2017 Prime Minister’s Prize for Innovation

Published 1 June 2017

Next time you’re racing out of the house without cleaning your teeth, think again. Neglecting your pearly whites can lead to a lot more than the odd filling.

It’s the simplest of actions, but brushing your teeth properly with a good fluoride toothpaste that produces plenty of white froth could save your life.

The worst most of us expect when we forget to brush and floss is plaque build-up and decay. But poor oral hygiene has also been linked to a range of conditions including some cancers, cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis and pregnancy complications.

It seems incredible, but it’s quite logical when you think about it.

A healthy mouth harbours small amounts of bacteria that don’t cause problems. In the right conditions, however, they can multiply, react with others and cause gum disease. In some cases, the untreated infection can travel through the gut and blood stream to other parts of the body, causing serious illness.

Gum disease is extremely common. One in three adults and more than 50 per cent of Australians over the age of 65 have moderate to severe periodontitis, which is caused by an imbalance of bacteria in the mouth.

It’s a huge and expensive problem. Oral health conditions alone cost an estimated $420 billion a year globally. Each year, preventable dental conditions put more than 60,000 Australians in hospital.

Health & Medicine

Predicting premmies: The test that could save babies’ lives

Led by University of Melbourne researchers, a global network of experts is working to improve the situation and potentially improve the health of millions of people.

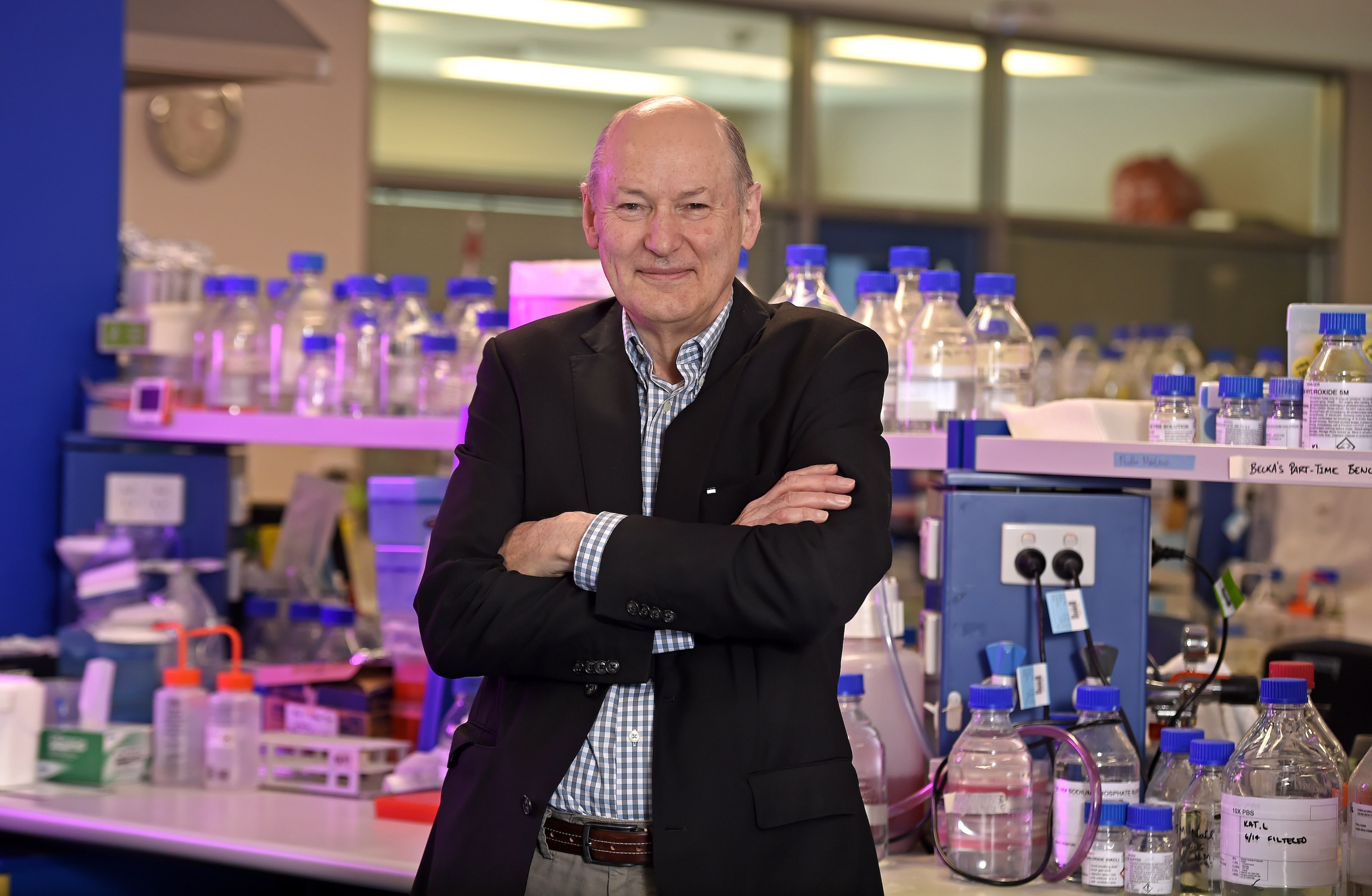

The Oral Health Cooperative Research Centre’s CEO, Laureate Professor Eric Reynolds, started his research in this field in the 1980s, when he discovered the tooth-protective properties of casein, part of the protein in cow’s milk.

Professor Reynolds and his colleagues developed RECALDENT™, which delivers calcium and phosphate to penetrate, strengthen and re-mineralise tooth enamel affected by plaque. It is sold in more than 50 countries.

Now, after 15 years in development, Professor Reynolds and his University of Melbourne team are inching closer to a world-first vaccine for a major contributor to poor oral health – chronic periodontitis, a destructive and progressive gum disease that affects one in four people globally.

It starts when the insidious bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis – or Pg – nestles in tooth plaque below the gum line. Pg subverts the host’s immune system, allowing other pathogenic bacteria to outnumber the beneficial bacteria in the plaque.

Most people have small amounts of Pg in their mouths that remain in “survival mode”. The trouble starts when Pg interacts with other bacteria and causes chronic periodontitis.

It may not throb like a toothache, but the condition erodes a tooth’s supporting structures, including gum and bone. This causes pockets to form and the gums to recede. If untreated, teeth can be lost.

Symptoms include gum inflammation and swelling, unexplained bleeding, bad breath and deepened pockets between the gums and teeth. This creates ideal conditions for the bacteria to multiply.

Many don’t realise something is wrong until the damage is done. “Some people don’t know they’ve got it until they’re brushing their teeth, or they touch their tooth one day and it’s loose,” Professor Reynolds says.

Research has shown that chronic periodontitis is associated with rheumatoid arthritis, pancreatic and some mouth cancers, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, dementia, gut inflammation, and pregnancy complications.

This occurs when gums are chronically inflamed, destroying supporting tooth tissue. “This inflammation allows Pg to invade the blood stream and establish in other parts of the body, which can then promote disease at these sites,” Prof Reynolds says.

With CSL Ltd, Professor Reynolds and his research group have developed a vaccine candidate to treat chronic periodontitis. Targeting two damaging enzymes only found in Pg, the vaccine triggers an immune response that produces antibodies to neutralise the pathogenic toxins.

Human trials could start as early as next year. If successful, the vaccine could eliminate or reduce the need for invasive treatments that now include professional cleaning, antibiotics and surgery.

Other exciting developments are helping scientists to understand and better direct oral health treatments. A recent international oral health conference hosted by the University of Melbourne, PGMelbourne2017, heard from experts such as the University of Louisville’s Professor Jan Potempa.

Professor Potempa’s research shows that the inflammatory response that Pg causes in the mouth has a connection to the inflammatory process that causes rheumatoid arthritis. Professor Potempa found that Pg antibody levels were higher in people with rheumatoid arthritis than those without the disease, and these antibodies could be detected in people up to 10 years before their arthritic symptoms emerged.

Such discoveries are helping Professor Reynolds and others in their quest to nip Pg in the bud.

In the meantime, you can minimise the chances of gum disease with good brushing and flossing using a soft brush in a circular motion. The toothpaste should create enough froth to coat the teeth, gums and tongue. This helps remove any bacteria.

“A lot of people just think they clean their teeth,” Professor Reynolds says. “But you actually have to clean the gum margin - it’s absolutely critical - and in between your teeth. Periodontitis starts in the gaps in between your teeth and around the gum. People are so focussed on tooth decay that they scrub the biting surfaces, which does nothing for periodontal disease.

“You should not only do your gums, in soft circular motions, you should clean the … top layer of your tongue as far back as you can go with the tooth brush and the tooth paste. Scrub it, froth it up. Because it’s that froth, the suds, that gets the biofilm … that harbours the bacteria.”

Start with about 45cm of floss

Move the floss back and forth and up and down against the side of each tooth

It’s important to go beneath the gumline to remove harmful bacteria

Gently curve the floss around the base of the tooth.

Never force the floss as this can damage gum tissue.

Use clean sections of the floss as you move from tooth to tooth

Professor Reynolds is the 2017 winner of the Prime Minister’s Prize for Innovation, recognising his invention and commercialisation of RECALDENT™.

In May the Australian Dental Association presented Professor Reynolds with an Award of Merit for his outstanding service to dentistry and dental education over more than 35 years. Since starting in the University of Melbourne’s Department of Preventive and Community Dentistry in 1978, he has conducted and supervised research published in more than 270 publications, won countless awards, given hundreds of lectures globally, secured 22 patents and attracted more than $100 million in research funding.

Banner Image: Shutterstock