Bubbly personality: how our biology hits budgets

Economics and neuroscience are coming together to help solve market bubbles and crashes, by investigating how financial decisions are tied to our biological makeup

Published 7 October 2015

When Professor Peter Bossaerts moves from the US to the University of Melbourne in January he will be facing a major financial decision: should he buy a house in what may be an over-inflated property market?

Professor Bossaerts, from the University’s Faculty of Business and Economics, has been studying issues like financial risk and how bubbles form in markets for almost 20 years but even he admits choices like this can be hard.

“I’m a finance professor - I’m supposed to know all this stuff - and it is still extremely difficult for me,” he says. “Most people don’t know much about markets and they are still asked to make very important decision and there is no real mechanism to help them out.”

Professor Bossaerts aims to remedy this with innovative new research that brings together cutting-edge ideas from economics, psychology and neuroscience.

This research will complement work already being done at the University of Melbourne’s Decision Neuroscience Laboratory, examining the science behind how we make decisions.

The professor, who grew up in Belgium, first became interested in this sort of cross-disciplinary approach – a method rare for his field - during the early 1990s while working in the finance and economics department at Carnegie Mellon University and later at Caltech.

After attending conferences in Melbourne for some years, the University offered him the opportunity to set up the lab - which was one decision that came easily.

“I started laughing,” Professor Bossaerts says today. “I said: ‘You know what? I’m a high maintenance guy because I want to set up an interdisciplinary lab and this is not easy.’ The Provost said: ‘We can do this.’

And so far, so good. It’s a puzzle that is coming together very, very nicely and I’m very happy with it.

Traditionally finance has shunned experimentation in the lab and looked instead at decision making using real world data mixed with abstractions; the individual is taken as a given unit in a market seeking to maximise utility as expressed through their choices.

The problem is, latest research suggests individuals do not adhere to economic theories very well. Instead, there is much behavioural variation that ties in with our biological makeup and psychological response to the natural world. This makes it difficult to deal with the very different sorts of risks that appear in financial markets, where outliers in price fluctuations are often irrelevant noise rather than a real signal of change like we would find in nature.

An analogy is when something like a cold snap hits it signals a change in real world conditions which we correctly respond to by grabbing our jacket when we go outside. But because financial markets do not work this way, humans, driven by biology, can be trapped by our own natural responses to them. This is where the lab work comes in.

“We want to broaden the exposure of finance to psychology because it is really needed,” Professor Bossaerts says.

We see all sorts of cognitive biases – certainly in a financial context.

One ongoing project is helping to explain the “disposition effect”, where investors sell too early on gains but hold onto their losses, which seems to have a strong biological basis.

Other areas of research include how drugs like Ritalin or nicotine affect decision-making in financial scenarios, and how humans interact with the automated robot traders which account for so much market activity today.

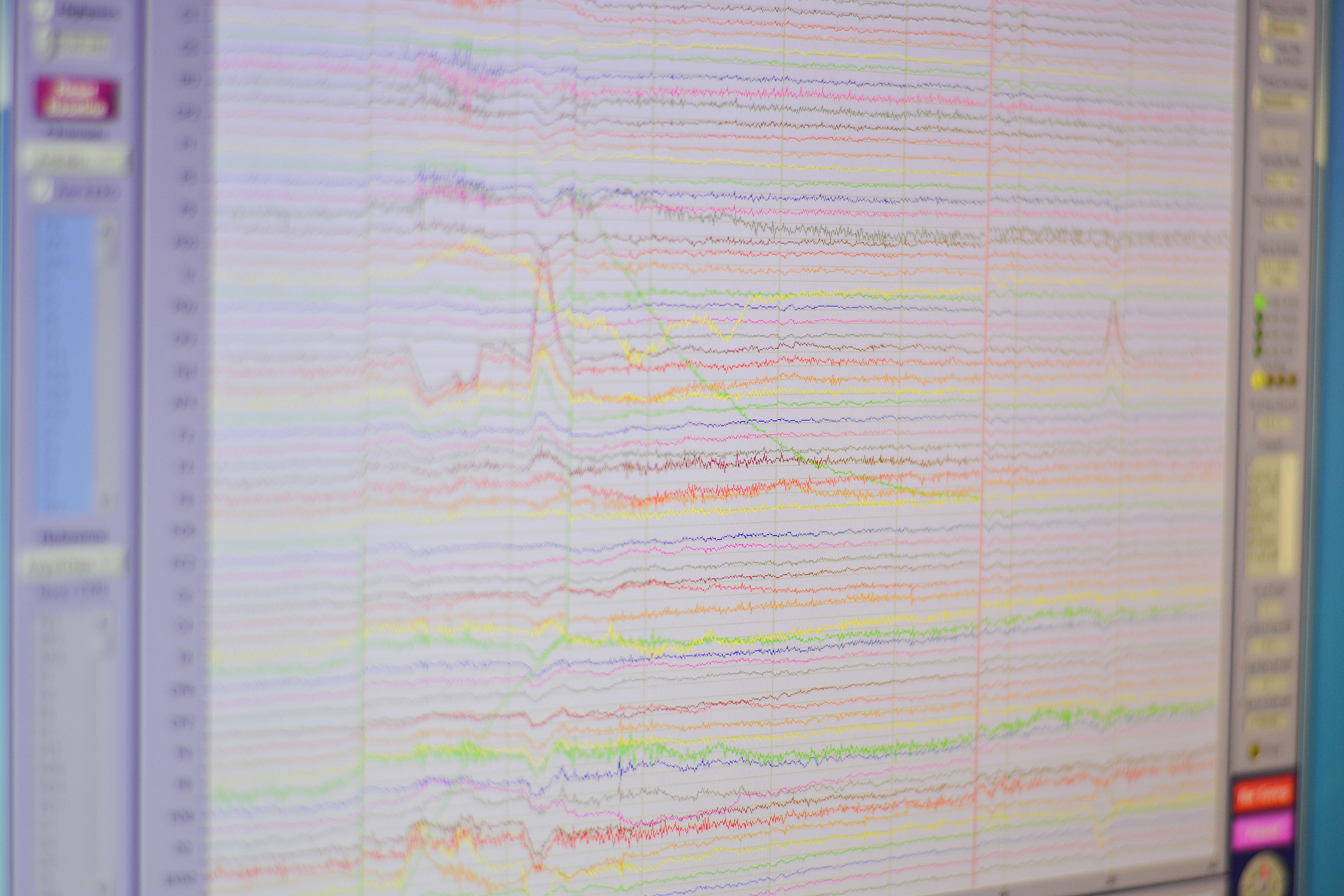

He aims to use the latest neuroscience imaging technology and computer modeling to investigate.

The professor says the work is of particular relevance to Australia where citizens are expected to take on far greater personal control over wealth creation and retirement funding than other areas of the world, through real estate investing and superannuation.

When he arrives, Professor Bossaerts will be working with the co-heads of the University’s existing Decision Neuroscience Laboratory: Dr Carsten Murawski from the Department of Finance and Dr Stefan Bode from the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences.

Doctors Murawski and Bode met in 2010 when Dr Murawski was looking for someone to analyse brain data taken from functional magnetic resonance imaging during an experiment on financial decision making.

Dr Bode, a lecturer in cognitive psychology and behavioural neuroscience, had the right skill set and found he was interested in the same questions too. The pair decided to apply for funding and set up the Decision Neuroscience Laboratory.

Their work so far has focused on questions like how we trade-off between rewards now and in the future: for example would you choose to take $20 now or $30 in a month?

The experiments show the point at which there is no real difference for the subject making the choice – much as if they were being asked a question with no real stakes, like whether to press a left or right button. At this point, subjects might be particularly susceptible to influences from the environment – through images like passive advertising.

The aim is to discover ways to prompt better decision making to tackle serious social problems like the retirement savings gap, obesity or excess gambling.

Dr Bode says participants in experiments have been shown pictures designed to trigger spontaneous reward responses – from images of the Apple logo to pizzas and pleasant social interactions like kissing.

“When you show very rewarding images you can prime people towards more spontaneous decisions,” Dr Bode says. “So they want more, now. Future-related mental images can also achieve the opposite and make you more patient. This is, for finance people, very interesting.”

Dr Murawski, whose background is in studying financial markets, explains: “We found the environment can play a very important role in those decisions, whereas historically economists would argue that people have certain preferences and their behaviour is an expression of those preferences.

“We showed we could actually bias them systematically in one direction. That suggests you could use certain environmental manipulations to get people to save more money for the future, for instance.

“The exciting aspect of the work is I see an opportunity, by using this new interdisciplinary approach, to develop interventions that will help people improve their behaviour and, through this, their wellbeing.

“What we would like to push in the near term is to link that research more closely with major societal problems.”

Recent work has found obese subjects are more susceptible to this sort of environmental manipulation than those of normal weight. The lab is working with the Cancer Council of Victoria on how to help deliver healthier messaging in a media environment saturated by imagery of the opposite.

Both Dr Bode and Dr Murawski are also looking forward to collaborating further with Professor Bossaerts when he arrives in town.

So will the professor be buying or renting?

Studies so far suggest those with a highly developed “theory of mind” – people who are good at social interactions and working out whether someone is an asset or a threat – have a greater tendency to ride bubbles. Professor Bossaerts says with a laugh, he is “not one of those guys”.

“If you are an asocial guy you simply say the price is too high. You don’t try to find intentionality behind these price changes.

“I think one has to be extremely careful jumping into the market. The real estate market is not very efficient – if it’s mispriced it can take a long time to correct.”

He says he will have to look at the question further once he arrives Down Under but his initial investigations into clearance rates are telling him to hold off: “I will not buy a house – certainly not in Melbourne itself – for the first six months or a year. I just want to wait – I do think this is a bubble that is about to burst.”

Banner image: 401(k) 2012 via Flickr