Environment

Australian Modernism’s Top 10: Part One

We’ve had qualified women architects in Australia for nearly 120 years, but there is no way that we’ve reached gender parity in the professions

Published 13 November 2019

Our designed spaces have an enormous impact on day-to-day life.

Sometimes overtly, and sometimes very subtly, our built environments shepherd us through space, influencing whether we have a positive or negative experience in a particular place.

Obvious examples would be allowing natural light into spaces having a positive influence on mental and physical health, adding a unisex toilet into a new building or reducing opportunity for crime by ensuring people can traverse cities in well-lit, populated open spaces as opposed to dark, narrow alleys.

It makes sense then, that we need a diverse body of professionals designing for a diverse community with diverse needs. However, this isn’t necessarily happening.

We’ve had qualified women architects in Australia for nearly 120 years, but there’s no way that we’ve reached gender parity in the professions.

Environment

Australian Modernism’s Top 10: Part One

We’ve had parity amongst the student body in these areas for the last 30 years. Why is it that when we look at the profession itself, we don’t see the kind of diversity that you would expect to see?

There’s something else going on in the professions that encourages women to go away. The leaky pipeline, as it’s called.

To address this lack of parity, there needs to be more focus on the systematic issues that are affecting the inclusion and retention of diverse staff, and the barriers within the built environment professions that can make a difference for women.

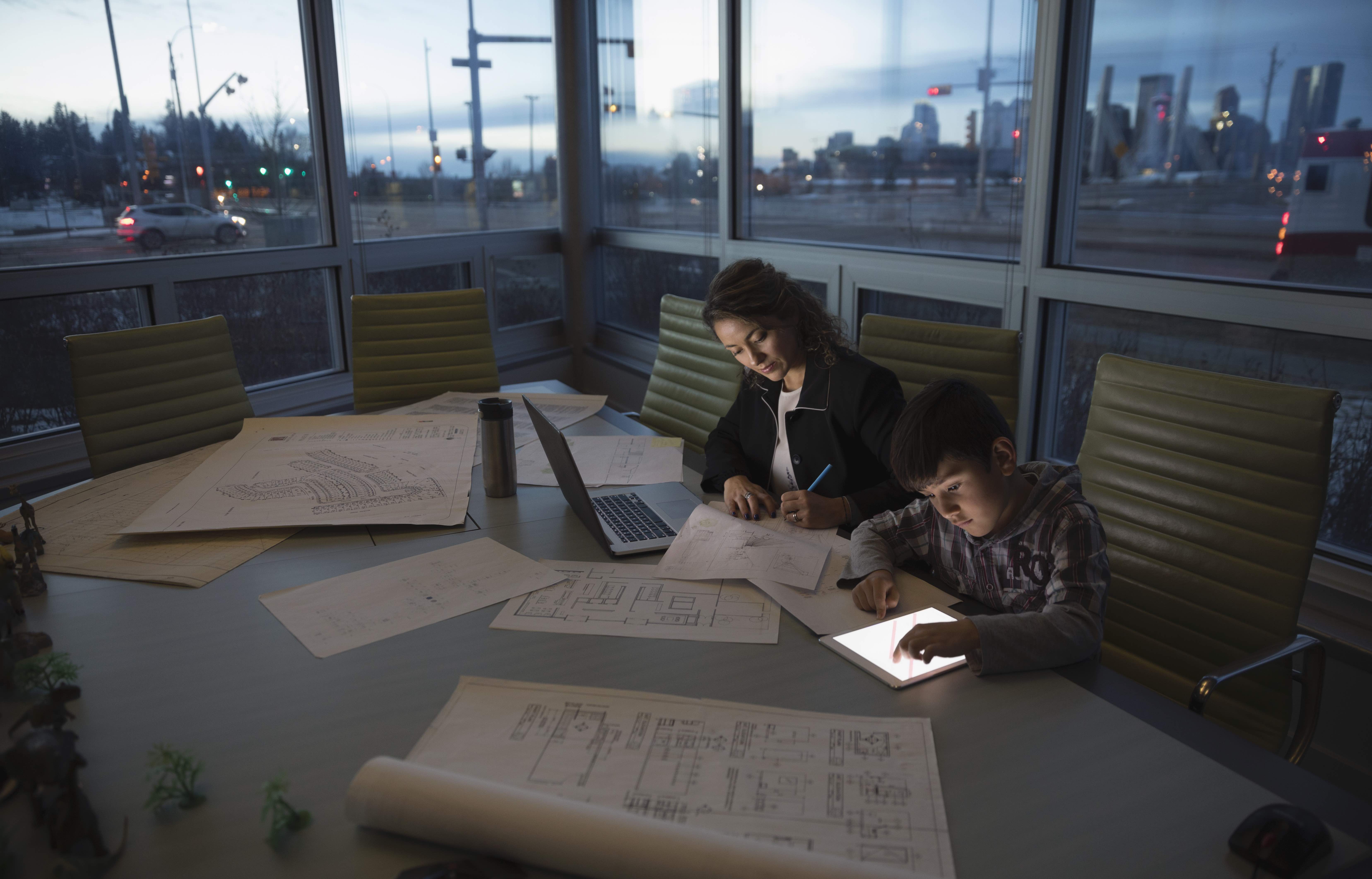

It’s not unusual, still, to have really long working hours in architecture.

Those conditions can make it very difficult for people to forge successful careers that enable them to have a family, a home and a work-life balance.

People have to make choices if the pay isn’t good enough and the conditions are bad. Many people leave, and not just women, because of those difficult working conditions.

We’re now starting to see firms making the welfare of their employees a key priority to improve staff retention and improve the outcomes for clients.

Environment

Australian Modernism’s Top 10: Part Two

It takes time and effort to do this, but it’s incredibly important.

The people who are in charge of firms are often males with a white, European background.

In an Australian society for people of a certain generation, that’s not altogether surprising.

But we see over time that women in particular have been shyer or less willing to take the gamble in setting up their own firm.

If you’re a mother with a small child, are you going to take the job that you just get paid for and you know the money’s going to come in, or are you going to take the risk and set up on your own, not sure whether the money’s always going to come in?

Women are also enculturated to be more careful about these kinds of things.

If we look at history, there were women in practice who found it incredibly difficult because their female clients would say to them, “I’d much rather a nice, dependable man than a woman architect. They know what they’re doing”.

That’s an inculturation that men are good at business and women aren’t.

Environment

Reconciliation at scale

It’s easy to make assumptions about who the leaders are and then look to find those people because that’s who we are taught to think the leaders are.

Only when you consciously put a different lens on and say, “but all the leaders can’t be white male of a certain generation”, that you start to actively promote other leaders, leaders who look different, who don’t fit the norms and expectations.

Issues of inequity in the built environment isn’t just about women, it’s about anybody who doesn’t fit the norm. We need to think about the barriers that they face.

What are the things that stop them being successful and having their talent recognised in full, celebrated, and understood? What are the simple barriers to engaging fully in a profession or a vocation? Is it the fact that the toilets aren’t right? Or you can’t get to them? Perhaps there isn’t the right ramp, or the right steps if you are differently abled?

If you’re transgender, are you made to feel comfortable in a space? Are you welcomed as an ordinary, functioning member of the firm? What makes it difficult to engage? What sends people away before they get to the front door?

Ultimately, talent comes from anywhere.

You don’t have to look a certain way or behave a certain way to have talent. But what we’ve got are a series of filters that mean the talent ultimately ends up the same.

We have to remove those filters so that talent can be seen in all its glorious forms.

People don’t need to accept inequity in built environment professions. They need to look for instances of best practice, and to push from both above and below to get to a more equitable profession than we currently have.

Firms need to think about this as a point of difference.

They should be screaming from the rooftops, saying they’re equitable firms because then they’ll get the best talent.

If that’s a young man saying, “I want to spend more time with my kids,” that’s just as powerful as a young woman saying, “I want to spend more time with my kids.” It shouldn’t be different.

The Transformations: Action on Equity symposium will be held at the University of Melbourne from 14 to 15 November. All are welcome to attend and be a part of the lively and incisive exchange on gender equity in the built environment professions.

Banner: Getty Images