Health & Medicine

A new weapon in the war against superbugs

Sepsis, when our immune response to infection attacks tissues and organs, is a major killer, but recent research suggests a megadose of vitamin C can reverse the damage

Published 10 February 2021

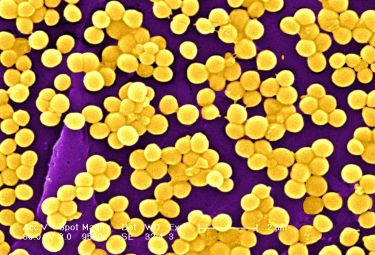

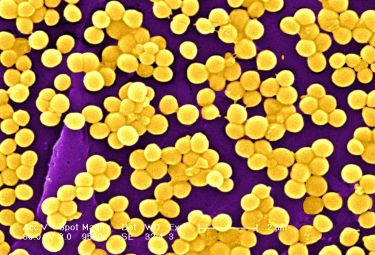

Sepsis is a condition when an excessive immune and inflammatory response to an infection starts damaging tissues and organs. The infective agent is most commonly bacteria, but can be a virus or even a fungus or parasite.

Sepsis is the main cause of death in Intensive Care Units and kills more people in Australia than breast, lung or bowel cancer. It is estimated that in 2017 there were 49 million cases of sepsis worldwide and 11 million deaths from the condition.

Sepsis accounts for an estimated 20 per cent of global deaths. As with any severe infection, patients with a severe case of COVID-19 can be at risk of multi-organ failure due to sepsis.

There are currently no treatments available to reverse the effects of sepsis. Rapid diagnosis and treatments including antibiotics, intravenous fluids and drugs that raise blood pressure are critical to maintain blood flow and oxygen delivery to susceptible tissues and organs.

Of those patients who survive, many have ongoing health problems, including cognitive and organ deficits.

Health & Medicine

A new weapon in the war against superbugs

The incidence of sepsis is increasing as a result of the ageing population and the growing menace of drug-resistant infections, which is a major threat to global health.

In April last year, in view of our research demonstrating the beneficial effects of large doses of vitamin C in septic sheep, a high dose of vitamin C was approved on compassionate grounds for use on a critically-ill COVID-19 patient at the Austin Hospital in Melbourne.

After 12 days, the patient had recovered enough to be taken off ventilation and was fit to go home after 22 days.

Human trials are now underway to establish the efficacy of the treatment in patients with sepsis, but why and how could large doses of vitamin C be a treatment for sepsis?

A focus of our research has been the acute kidney injury that that occurs in up to half of sepsis patients and which is associated with increased risk of death.

We have developed a technique to continuously monitor the levels of blood flow and oxygenation in different parts of the kidney and have shown that in early sepsis in sheep, blood flow and oxygenation falls in certain areas, which we suspect contributes to the later development of acute kidney injury.

We hypothesised that these changes contributed to the development of oxidative stress – an imbalance where the level of anti-oxidants in the body are inadequate to counteract free radicals (unstable molecules) that cause cell damage. Vitamin C, as a naturally occurring antioxidant, was an obvious target for potentially reversing the damaging effects of sepsis on the kidney.

Vitamin C is an essential nutrient for humans, who unlike most other animals lack the enzyme to synthesise it. We must therefore obtain it through our diet.

Health & Medicine

Translating thought into action

In addition to being an antioxidant, vitamin C has several other properties that may be of benefit in sepsis, including acting as an anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, immune stimulant and as an antibacterial. It also has an ability to stimulate synthesis of chemicals that improve blood pressure and therefore tissue blood flow and oxygenation.

The rationale for the use of vitamin C in sepsis is further enhanced by the knowledge that vitamin C levels in blood decrease significantly in sepsis to levels similar to those in scurvy.

Recently, several clinical trials have examined the use of vitamin C as a treatment in septic patients. The doses used in these studies (6-14 g/day) are very high compared with the normal daily requirement of 75-90 mg/day. In these studies, vitamin C – or its mineral salt form sodium ascorbate – were administered intravenously because there is a limit on the amount we can absorb by taking it orally.

Although these studies showed a trend for improvement, the effects were mild and the use of high-dose vitamin C in sepsis remains controversial.

However, we do know that much higher doses of vitamin C (up to 120 g/day) have been used without side-effects for the treatment of burns and cancer, but the effects and safety of such megadoses have not been examined in critical illness.

Health & Medicine

The right antibiotic at the right time

In a recent study, published in Critical Care Medicine, we examined the safety and efficacy of a megadose of intravenous sodium ascorbate in established sepsis in sheep. We gradually infused a total of 150 grams of sodium ascorbate – the equivalent amount of vitamin C in about 2,500 oranges.

During the infusion, the dose of the clinically used drug noradrenaline (which is required to restore blood pressure in septic sheep) was dramatically reduced, whereas the dose had to be progressively increased to support blood pressure in the placebo-treated sheep.

In addition, the blood flow and oxygenation increased in the inner zone of the kidneys of the treated sheep and the function of the kidneys dramatically improved.

The level of oxygen in the arterial blood increased, suggesting improved lung function. The concentration of lactate in the blood decreased indicating a reduction in the severity of disease, and the sheep’s high body temperature fell back to normal.

A further striking finding was the remarkable improvement in clinical condition. From demonstrating malaise, lethargy and unresponsiveness to external stimuli, within three hours of infusion of sodium ascorbate, sheep became alert, responsive, and mobile.

They stood up, started drinking and eating, and looked well.

It was these highly promising results that encouraged our long-term clinical collaborator, Professor Rinaldo Bellomo at the Austin Health’s Intensive Care Unit, to try out the treatment as compassionate use on a critically ill COVID-19 patient suffering acute respiratory distress syndrome, low blood pressure and acute kidney injury.

Health & Medicine

What chickens can tell us about living with COVID-19

A loading dose of intravenous vitamin C (30 grams over 30 minutes) was followed by a maintenance infusion (30 grams over 6.5 hours) – blood pressure improved, heart rate decreased and there were improvements lung and in kidney function.

The patient was discharged from hospital without any complications, about three weeks after the treatment.

Clinically it is vital to confirm that these findings translate to septic patients. To this end, a clinical trial of intravenous sodium ascorbate in septic patients has started at the Austin Hospital and additional trials are planned at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Monash Health.

Hand-in-hand with these clinical trials, our research at the Florey is determining the optimal dose of vitamin C and will investigate the mechanisms by which it has such potent and widespread effects to improve organ function in sepsis.

For further information about symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of sepsis visit the Australian Sepsis Network website.

Banner: Getty Images