Health & Medicine

Taking the guesswork out of concussion

Research suggests that chronic fatigue is linked to gut bacteria and how our bodies convert food into energy

Published 9 January 2017

As the New Year gets going, are you still feeling tired and run down? Do you feel like you could sleep for a week and that you’ve reached the limit of your energy? Some regular sleep is probably all you need to revitalise you. But for some it’s nowhere near that simple.

What if your fatigue is so severe that you have had to substantially cut down on regular work, education or social activities?

This is what people with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), or myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), experience. As the name implies, ME/CFS is a chronic, often severely disabling disease that comes with a myriad of symptoms rooted from the autonomic nervous system, immune system, endocrine system and gut. A good night’s sleep is not going to fix this severely debilitating disorder and treatments are hard to come by.

People with ME/CFS commonly experience headaches, muscle and joint pain, unrefreshing sleep, irregular heartbeat, shortness of breath and problems in thinking and memory. They may not be able to regulate body temperature, and experience visual disturbances and extreme photosensitivity, balance problems, and irritable bowel, among other symptoms.

ME/CFS is prone to being misdiagnosed, and there are concerns that many health care providers still mistake it for a mental condition. US medical research funding agency the National Institutes of Health announced in 2015 that it was increasing research funding into ME/CFS.

Chris Armstrong, a researcher at the University of Melbourne’s Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute and the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, is the lead author on some recent studies that associate metabolites and microbiota in faeces, blood and urine with ME/CFS.

Health & Medicine

Taking the guesswork out of concussion

Together with a clinician, Dr Donald Lewis, he has been obtaining urine, blood and faecal samples (after overnight fasting) from 34 people diagnosed with ME and from 25 people who are not affected. All participants in the study are women, as sex significantly influences results and also because proportionally greater numbers of women are diagnosed with ME.

With the help of his University of Melbourne supervisor, Bio 21 research group director Associate Professor Paul Gooley, Mr Armstrong used magnetic resonance spectrometry to explore whether there were any differences in the energy metabolism of people with ME/CFS.

He ran his samples through magnetic resonance spectrometers to look for changes in the levels of the major metabolites in faeces, blood and urine, which include the amino acids, glucose, short chain fatty acids (SCFA) and organic acids.

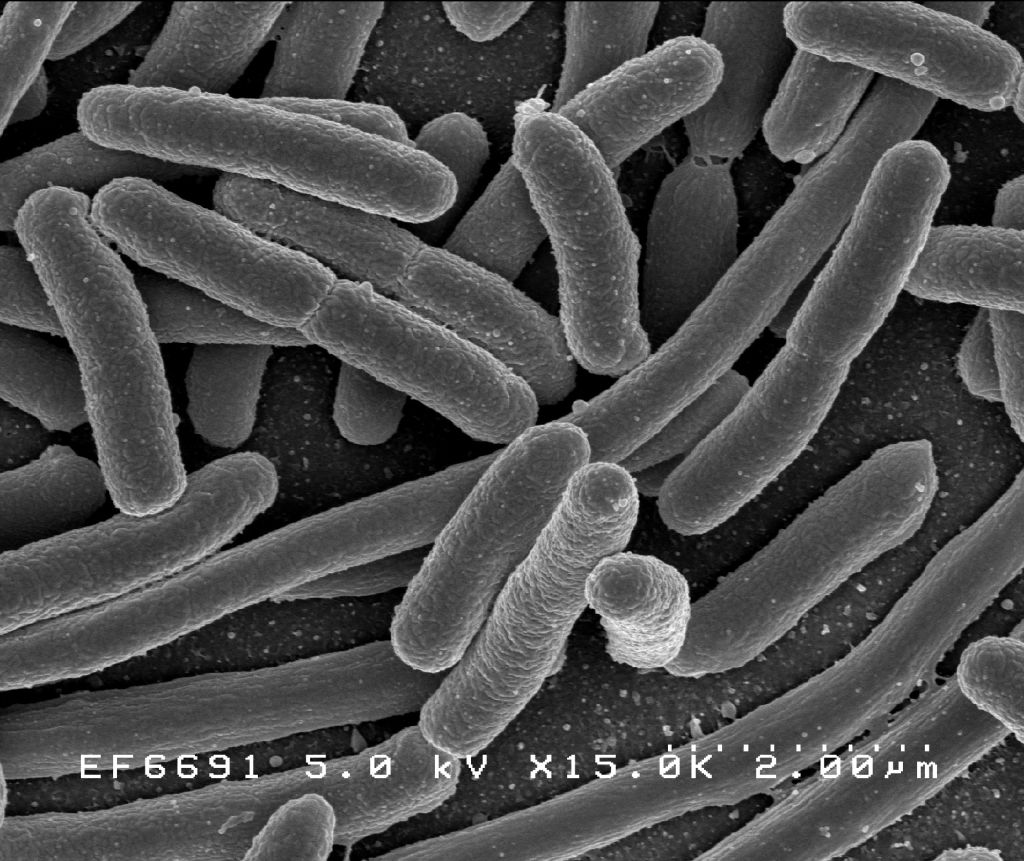

At the heart of the problem is energy – how our body metabolises food and converts it to a usable form of energy. Another part of the equation is our commensals: the bacteria in our gut, which also gain energy from our food.

Building on his lab’s previous work, which found altered gut bacterial populations in patients suffering from ME/CFS, Mr Armstrong published findings showing changes of metabolites in the blood and urine of ME/CFS patients. These changes hinted at a slight but significant shift in the body’s source of energy production: from sugars to amino acids. Also, Mr Armstrong observed that biochemical pathways associated with cell and tissue damage as a result of oxidative stress were more active.

The complexity of ME/CFS means that by its nature, the research spans a number of disciplines, particularly metabolomics, microbiology and immunology. Both of Mr Armstrong’s studies have been ground-breaking across these disciplines.

The results from his most recent publication confirm differences in gut microbiota in people with ME/CFS across blood, urine and faecal biofluids, as well as elevated levels of short-chained fatty acids (SCFA) at the expense of amino acids, due to more fermentation taking place in the gut of ME/CFS patients.

Working together with Dr Neil McGregor, former editor of the Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Dr Henry Butt, director of medical laboratory Bioscreen, Mr Armstrong wanted to see whether there were correlations between his observations in metabolism in his samples and the presence of certain types of bacteria.

As suspected, he found that not only were there differences in the energy metabolism of people with ME/CFS, but that these are correlated to their gut microbiota.

How can the bacteria in the gut be making people feel tired?

Health & Medicine

The immune legions fighting Legionnaires’ disease

It’s early days, but the research is hinting that the composition of the gut bacterial populations (good gut guys vs bad gut guys) could be skewing the body’s metabolism away from obtaining energy from glucose in the process of glycolysis (glucose to energy), to gaining energy from fats and proteins.

This is akin to what our body does when it is starving and it may be a possible explanation for the lack of energy people have in ME/CFS.

More research needs to be done on how the energy metabolism pathways of our body (that is, the citric acid cycle) can be affected by gut bacteria.

“ME/CFS is a complex condition and to find the answer, we need to take a whole-body approach,” argues Mr Armstrong. “And the new knowledge gained in metabolomics and systems biology will make it possible to delve into the complexity of our body’s metabolism.”

Banner Image: Pexels