Politics & Society

Closing the Gap: time for traction on the ground

Blindness is a devastating disability that impacts disproportionately on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, but the good news is that some solid progress is being made

Published 30 October 2017

Back in 2008, the National Indigenous Eye Health Survey found by the age of 40 and above Indigenous adults had six times as much blindness than non-indigenous people. This, despite the fact that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children had much less poor vision than non-indigenous children.

But 94 per cent of this vision loss is unnecessary and could be prevented, or treated.

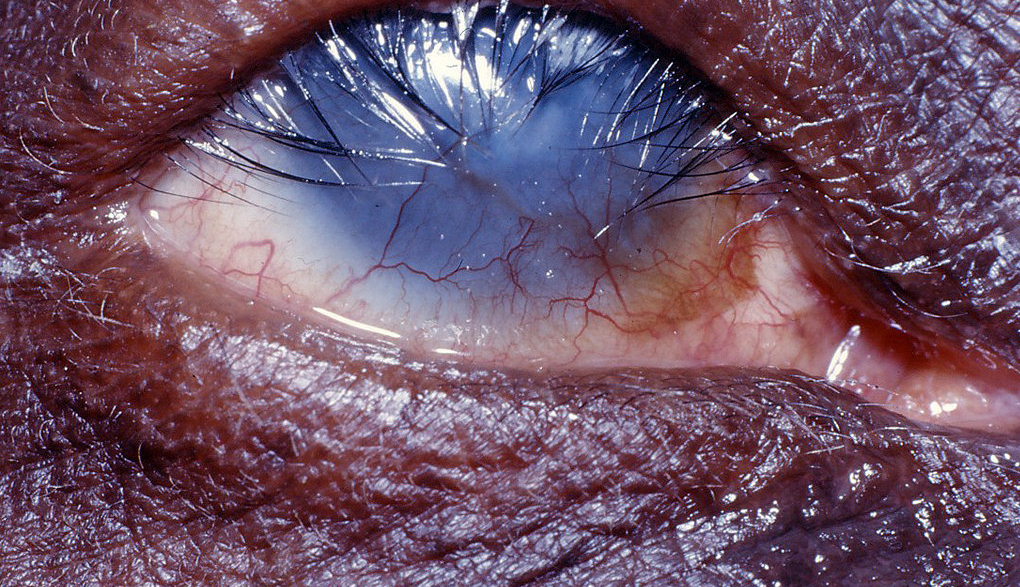

The survey identified four main causes for this loss of vision; cataract, diabetic eye disease, refractive error and trachoma – a blinding eye infection that still occurs in Australia’s outback areas.

Surprisingly, the amount of vision loss was the same in the cities and towns as it was in remote areas. The unmet need in Melbourne’s central Fitzroy was the same as in Fitzroy Crossing in remote Western Australia.

In Fitzroy Crossing, more optometry and ophthalmology visits are needed, but the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service in Fitzroy is less than a kilometre of the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, the largest eye hospital in the Southern Hemisphere.

What was needed across the country was proper planning and coordination to make sure that eye care services were appropriate and accessible.

Five years ago, after extensive consultation with community groups, organisations and providers, we developed the sector-endorsed Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision that had 42 recommendations for changes in the way eye care services were organised, coordinated, funded and monitored.

Now, the Indigenous Eye Health group at the University of Melbourne is reporting on the progress made over the last 12 months. And there is some good news.

Last year, the National Eye Health Survey reported the gap between Indigenous and non-indigenous rates of blindness had been halved and sat at “only” three times. Although this is still not acceptable and there is more work to be done, clearly eye health is one area where the Gap can be closed.

The 2017 Annual Update reports that some remarkable progress has been made. The first step on every recommendation has been made, more than two thirds of the intermediate steps have been taken and 16 of the 42 recommendations have been fully implemented.

The last 12 months has also seen the progressive uptake of the new Medicare Item for retinal screening for those with diabetes and the delivery of the first of the Commonwealth-funded retinal cameras to Aboriginal Medical Services.

Trachoma is an eye infection that occurs when young children are repeatedly reinfected causing inflammation that leads to scarring and blindness in adults. It remains a problem in the outback areas of South Australia, Westerns Australia and the Northern Territory.

According to the most recent data available, good progress has been made in reducing trachoma rates in children in the outback areas from 21 per cent in 2008 to less than 5 per cent in 2015,. This is largely due to concerted efforts to screen and treat children and their families, as well as the the health promotion messages around Clean Faces, Strong Eyes.

But this relies on access to safe and functional washing facilities that are properly maintained. And, that in turn, requires breaking down any cross-portfolio barriers between jurisdictional departments of health, housing and education so that bathrooms and washing facilities in houses and schools are in good working order.

Although there is leadership at the higher levels, there needs to be real cooperation between services at the regional and local level.

As part of the report, we studied the patient journey, or the pathway of care, and likened it to a leaky pipe. There were many leaks or cracks where people could fall out of the system. If you only stopped one or two leaks the pipe would still be leaky, you needed to address them all.

One key component in the improvement of eye care is the development of coordinated regional models of care that bring together the key stakeholders; the Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, the hospitals and local health department, the Primary Health Networks and the eye care providers – optometrists and ophthalmologists.

Politics & Society

Closing the Gap: time for traction on the ground

And this approach is effective. The regional group maps the gap in services, arranges the appropriate coordination and provision of care and meets regularly to assess progress. A dedicated regional implementation manager is key to facilitating this process. While there is urgent need for appropriate funding for such managers in the remaining regions, a request for this has sat with the Commonwealth for several years.

This is also necessary to ensure that the development of functional eye services does not wane, and in fact continues to expand throughout the whole country.

Eye care is one of many issues that need to be addressed with Indigenous Australians and health. But vision loss was responsible for around 11 per cent of the health gap, close behind heart disease and diabetes, and ahead of stroke and alcoholism. Unlike these other conditions, most of the disability from vision loss can be fixed overnight.

These lessons from the provision of eye care can deliver a template for the development and linkage of other specialist services. What works for eyes will work for ears or hearts or lungs or kidneys.

Addtionally, the health promotion and hygiene changes for trachoma have a much wider impact than just trachoma. For example, you can’t wash your face without washing your hands. The improvement in hygiene reduces ear infections, respiratory infections, diarrhoea and the skin infections that lead to rheumatic heart disease and kidney failure.

So, a focus on eye care has much broader ramifications than just saving or restoring vision. It improves the quality of life of the individuals, frees the family or community members who are carers, reduces the other important infectious diseases and it provides the exemplar for how other specialist services should be designed and coordinated.

The strong progress made for eye care and vision is one area where the gap really is being closed. But if we are to actually Close the Gap for Vision by 2020 we still need to make sure that all the recommendations in the Roadmap are fully implemented.

This means providing well-coordinated, accessible and accountable eye care services that are fully functional in all regions across the country and making sure blinding trachoma is eliminated.

Banner image: Indigenous Eye Health, The University of Melbourne