COP29 wrap-up: Urgent finance needs stall in Baku

PhD students working in climate-related fields give their analysis of the successes – and failures – at the COP29 climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan

Published 26 November 2024

Climate leaders and advocates looked to this year’s climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan – dubbed the ‘finance COP’ – to establish adequate funding to help developing and small island states address the current and future impacts of climate change.

Emerging climate researchers from the University of Melbourne give us their read on the success (or otherwise) of the conference.

Navam Niles: “Agreement is incremental and ambiguous”

Navam is a PhD candidate in the School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences.

While much of the focus was on climate finance (and geopolitical tensions), the negotiations also addressed the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) established in the Paris Agreement.

The GGA aims to “enhance adaptive capacity, strengthen resilience, and reduce vulnerability to climate change” while supporting sustainable development and keeping warming well below 2°C.

An agreement to include work towards the GGA in Biennial Transparency Reports was a positive development.

For developed countries, the inclusion of adaptation details is mandatory, aligning with the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience, and is expected to enhance the visibility of adaptation globally by compelling comprehensive reporting.

For developing countries, however, the inclusion of adaptation information remains voluntary, reflecting flexibility provisions under the Paris Agreement.

This transparency will feed into the second global stocktake in 2028, establishing a feedback loop for continuous improvement.

However, the new agreement is ambiguous about prioritising vulnerable groups and addressing regional disparities. For example, the agreement highlights gender-responsive approaches and the need to include vulnerable populations, but lacks enforceable mechanisms.

COP29 called for consolidating more than 5,000 adaptation indicators reviewed in the UAE–Belém work programme, spanning eight key domains including water resources, food security and health into about 100 globally relevant metrics – aiming for coherence while allowing voluntary adoption based on national circumstances.

While this is progress, the UAE–Belém metrics do not adequately address regional data disparities or provide strategies for incorporating Indigenous and local knowledge.

Balancing global uniformity with differentiated capacities remains unresolved.

A key theme at COP29 was transformational adaptation – which results from major activities like large-scale shifts in resource management and long-term societal transformations towards sustainable development.

However, there were concerns that the concept was introduced prematurely and lacks operational clarity. It requires further refinement before meaningful adoption will occur.

Jason Titifanue: “Just transition pathways”

Jason is a Rotuman, and PhD Candidate with the School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and Research Fellow at the Oceania Institute.

If we fail to construct our own realities other people will do it for usEpeli Hau'ofa, 2000

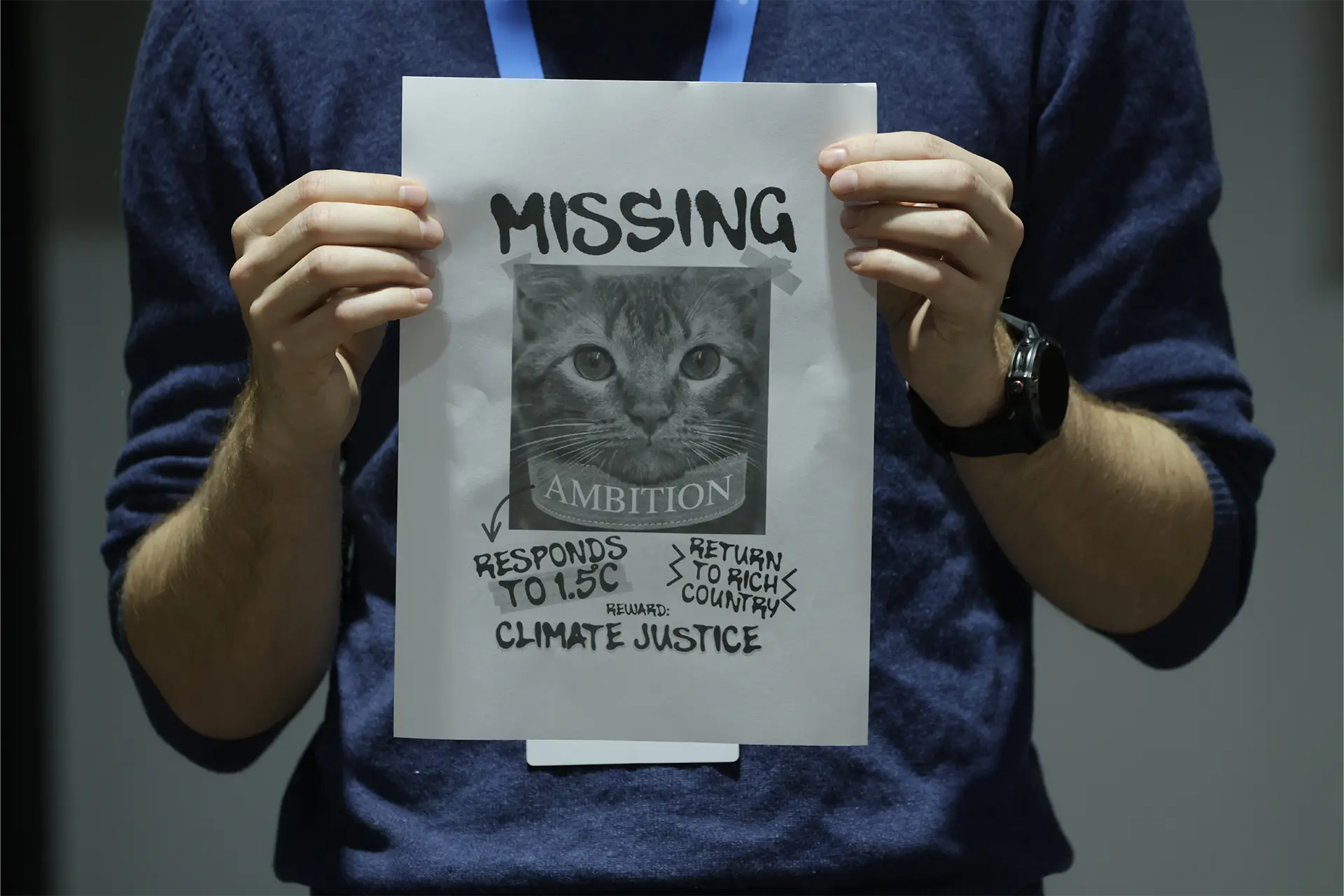

The third UN climate conference in a row to be hosted by an oil-producing nation, this COP, like its antecedents, was characterised by Global North attempts to stonewall Global South demands and frame incremental action as somehow being transformative.

For Pacific Islands and their Peoples, the slogan of “1.5 to survive” is not merely a cliché. However, the draft decisions contained only mild language around goals to hold temperatures to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels with an aim of pursuing 1.5°C.

When coupled with findings that current Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are inadequate to contain heating to 2°C, much less 1.5°C, the reality is quite simple: the Earth is warming, and this COP has failed to take stronger action.

Environment

Crunch time at COP 29 requires a new deal

This COP underlined the importance of just transition pathways, which aim to leave no one behind as the world transitions to net-zero economies, and urged parties “towards achieving just transitions to net zero emissions (NZE) by or around mid-century, taking into account different national circumstances”.

While seemingly encouraging, these lofty aspirations must be evaluated within the reality of a new resource scramble triggered by NZE ambitions.

Increased demand for minerals needed for green technologies takes on a grimmer connotation when factoring in the emergence of new extractivist frontiers in the form of Deep-Sea Mining (DSM).

Proponents of DSM have sought to position their extractive industry as a sustainable means to address climate change, while also helping Pacific Island States address past injustices.

There have been some incremental positives at COP29 and there will be efforts by some to frame this as a positive transformative reality for the world. However, the bleak reality is that the overall outcomes of COP29 are yet another failure to take strong action on reducing warming.

COP29 is only positive for the greenwashing and justice washing of continued capitalism and extractivism.

Zoe Nay: “Fighting for a better climate future”

Zoe is a PhD candidate in Melbourne Law School and Research Fellow at Melbourne Climate Futures

One of the key priorities of the Pacific was ensuring COP29 delivered on climate finance.

This included a call for minimum allocations of finance for small island states and least developed countries, as well as guarantees for grant-based finance directed towards climate-related loss and damage.

Pacific Island countries and other climate-vulnerable countries called for developed countries to provide US$1.3 trillion a year in climate finance – which itself is only a fraction of their actual needs.

However, developed countries agreed to ‘take the lead’ in raising only US$300 billion a year for developing countries by 2035.

The COP decision on the new climate finance goal calls on “all actors to work together” to scale-up finance to US$1.3 trillion per year by 2035.

But there is no binding commitment to provide this finance, nor any minimum allocations of finance to small island states and least developed countries.

Politics & Society

What came out of the Samoa CHOGM

There is also no commitment to finance for climate-related loss and damage, only acknowledgement that significant gaps remain in responding to the increased scale and frequency of loss and damage.

Overall, some progress was made but not at the speed and scale to meet the needs of climate vulnerable countries, including those in the Pacific.

COP29 leaves important questions unresolved about who will provide climate finance and how to ensure it is accessible to those most vulnerable.

For the Pacific, it has raised further questions about how to protect lives, livelihoods and their connections to land and sea.

What is clear is that the Pacific is not only at the frontline of climate change, but also at the forefront of climate leadership.

As the Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum, Baron Waqa, made clear, if “we save the Pacific; we save the world” – and the Pacific will continue fighting for a better climate future.

Rebekkah Markey-Towler: “Tiny bright sparks”

Bek is PhD candidate in Melbourne Law School and Research Fellow at the Sustainable Finance Hub, Melbourne Climate Futures

COP29 needed to be a finance COP, but throughout the negotiations, there was little agreement as to who should contribute and how much.

And other developments around the COP did not bode well for keeping 1.5°C and 2°C alive.

Donald Trump was re-elected as President of the United States. A new report found that current nationally determined contributions to reduce emissions, if they are indeed met, will lead to a temperature rise of 2.6-2.8°C.

But perhaps one of the tiny bright sparks from COP29 has been around the role of corporations and the financial sector.

On 12 November 2024, the Hague Court of Appeal handed down its decision in a case brought by Dutch environmental organisation Milieudefensie and others against Shell, demanding the company reduce its CO₂ emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 relative to 2019 levels.

While it was disappointing that the Court found that Shell was not required to reduce its CO₂ emissions by the specific amount, it did confirm that Shell has a duty of care to protect Dutch citizens from dangerous climate change.

In addition, a report from the High-Level Expert Group on Net Zero Emissions Commitments from Non-State Entities found that voluntary commitments and transition plans by businesses are become more mainstream, although only a fraction of these are 1.5°C aligned.

Finally, the outcome text on climate finance does at least recognise the gap between what has been promised by countries and what is needed.

It calls on all actors, including private sources, to scale up financing to developing country parties to at least US$1.3 trillion per year by 2035.

So these developments are not perfect. There is still much to be done. But hope is not lost yet, especially if the private sector can help to lead the way.