Politics & Society

More Jaw Jaw: Stopping North Korea going critical

As US President Donald Trump and North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un fling insults at each other, many of those watching have asked the question: could lobbing mockery lead to lobbing missiles?

Published 7 December 2017

Since February this year, North Korea has fired 23 missiles during 16 tests. Analysts have estimated that the missiles may have the capability to reach much of the world, including Washington, DC. This development, combined with North Korea’s apparent success in miniaturising a nuclear warhead, has precipitated the current crisis.

But it’s Donald Trump’s erratic response to rising threat levels that has many people worried.

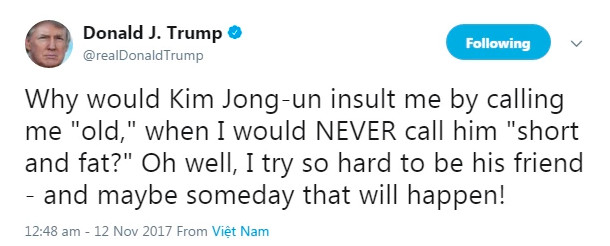

The President has alternately rejected and praised diplomatic efforts, just as he has both complimented Kim Jong-un and threatened Pyongyang with destruction. Of deep concern to many observers is that he seems personally offended by Kim Jong-un’s actions and words. In typically hotheaded tweets, he has called Kim “Little Rocket Man”, a “sick puppy” and suggested that Kim was “short and fat”.

To critics, Mr Trump’s behaviour is evidence that he cannot control his emotions. And when it comes to international diplomacy, Trump’s emotion-driven responses may be dangerous.

Democratic Senator Jeff Merkley says that Mr Trump is “trapped in a childhood emotional state”. The official Chinese news agency has criticised the president’s “emotional venting” on the issue of North Korea’s nuclear capabilities.

Politics & Society

More Jaw Jaw: Stopping North Korea going critical

A group of psychiatrists and mental health experts recently released a statement warning that Mr Trump is showing signs of “increasing loss of touch with reality, marked signs of volatility and unpredictable behaviour, and an attraction to violence as a means of coping”. Some who have known him for years, such as The Art of the Deal ghostwriter Tony Schwartz, say that the President is “losing his grip on reality”.

In addition to his impulsivity, the stand-off with North Korea is made vastly more dangerous thanks to two of Mr Trump’s deeply ingrained dispositions.

Donald Trump personalises issues and international relationships to an extreme degree. As part of an ongoing research program on emotions and personal diplomacy, we have found that personal relationships between leaders often have decisive significance, partly because every leader finds it a challenge to draw a clear line between their own personal interests and the national interest.

They find it difficult to disentangle the priorities of the country they represent from their own personal standing and reputation, and they can often place too much weight on displays of respect, deference, and admiration.

President Richard Nixon, for example, prolonged the Vietnam War in ways that undermined US interests partly because he feared the stigma of becoming the first president to lose a war, all while telling himself he was doing it for the good of the nation.

For many, Mr Trump is similarly losing sight of what is best for America – and the world – in favour of obsessing over what he believes to be personal slights.

“I try so hard to be his friend”, says one tweet about Kim. Our research suggests the plea is meant literally: Mr Trump conflates interpersonal and international relations.

And, concerningly, it seems he is making decisions about North Korea without the guidance of his own experts.

Evidence suggests Mr Trump has always had an exaggerated sense of his own knowledge and intelligence. Asked during the campaign where he gets advice about foreign policy, Trump said: “I’m speaking with myself, number one, because I have a very good brain and I’ve said a lot of things”.

He also appears to overestimate the efficacy of missile defence, claiming that the US has “missiles that can knock out a missile in the air 97 per cent of the time“, an assertion that has been questioned by international experts.

When President John F. Kennedy was confronted by the Cold War’s greatest nuclear crisis, he called together his top aides and spent days debating options. At the time, hawks on the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, known as ExComm, argued that Nikita Khrushchev’s secretive installation of nuclear missiles in Cuba should be met with air strikes and possibly invasion.

More cautious advisers urged diplomacy and a path that would allow the Soviet leader to save face. In 1962, the world came perilously close to all-out nuclear war. That outcome was avoided because the President consulted, deliberated, and – relying on counsel from people who knew the Soviet system – chose a combination of backchannel diplomacy and military resolve.

Patiently, carefully, Mr Kennedy found a way to convince Khrushchev to back down. But Donald Trump has no ExComm.

If he had simply asked his State Department’s North Korea experts why Kim called him a “mentally deranged US dotard”, they would have told him that the North Korean propaganda machine consistently churns out such abuse. Pyongyang’s creativity with insults is well known; they heap scorn on outsiders as a matter of course.

Their state news agency described Hillary Clinton as “by no means intelligent” and said that she resembled “a pensioner going shopping”. Barack Obama was called a “clown” and a “juvenile delinquent”, among other often racist affronts. Former South Korean president Lee Myung-bak’s government was belittled as a “group of traitors [that] reminds one of the rat-like hoodlums being dragged to gallows”, while Lee’s successor, Park Geun-hye, was demeaned in deeply sexist terms: “The swishes of Park Geun-hye’s skirt, created by her American boss, are so unpredictable they’re dumbfounding”.

Such statements are best regarded as ceremonial incantations, not serious threats. As with post-revolutionary Iran, where “death to America” became an everyday saying, Pyongyang’s ritualistic bluffs to subject the United States to “miserable destruction” should be taken with the Pacific Ocean’s worth of salt.

North Korean propaganda, like their policy of becoming a nuclear power, has been consistent. It is Donald Trump who has veered around wildly, lashing out against insults that should not be getting under his famously thin skin.

His impulsivity, his resistance to expert advice, his conflation of self and state: all these mean that words could indeed lead to war.

Banner: Getty Images