Designing homes for extreme weather

The devastating effects of extreme weather mean we must design homes to protect human life and buildings. Failure to do so risks some areas becoming ‘uninsurable’

Published 6 September 2022

From record-breaking floods in New South Wales to fires in Europe, extreme weather events are all around us. They are destroying homes and communities across the globe, with devastating outcomes for our natural and built environments.

What is extreme weather?

Extreme weather events like bushfires, floods, cyclones and extreme heat are formally defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as “an occurrence of a value of a weather or climate variable beyond a threshold that lies near the end of the range of observations for the variable”.

Exceeding these thresholds is a long-term worsening trend all over the world.

In Australia, heatwaves have increased in duration, frequency and intensity in many parts of the country; heavy rainfall events causing floods have increased and extreme fire weather days have increased at 24 out of 38 sites from 1973-2010, due to warmer and drier conditions

These events have strikingly demonstrated that our buildings are not designed to withstand this kind of natural force, leaving many people homeless and in some cases uninsured, at a huge cost to governments and society.

The financial impacts are already being felt, the destructive flood that swept through South-East Queensland and Northern New South Wales in late February and early March 2022 caused $AU4.8 billion in insured damages and is the third costliest extreme weather event in Australia’s history

These events increase the risk to lenders, with the Commonwealth Bank Climate Report 2022 identifying more than $AU 31 billion of home loans are in areas exposed to increasing extreme weather.

The Climate Council also estimates that by 2030, one in every 25 properties across Australia will be considered ‘high risk’, meaning they will be uninsurable due to the annual damage costs from extreme weather events

All of this leaves homeowners at increasing risk.

Protecting our buildings against extreme weather

The good news is that extreme weather-resilient buildings are already possible and can prevent further damage to the environment and the economy, despite existing houses remaining at risk.

A good example of extreme weather design working well is the updated Northern Territory building regulations following Cyclone Tracy in 1974, which caused 65 deaths and damaged 70 per cent of Darwin homes.

Encouragingly, more recent cyclones Vance (1999), Larry (2006) and Yasi (2011) showed that updated regulations and standards resulted in much less building damage and consequent loss of life.

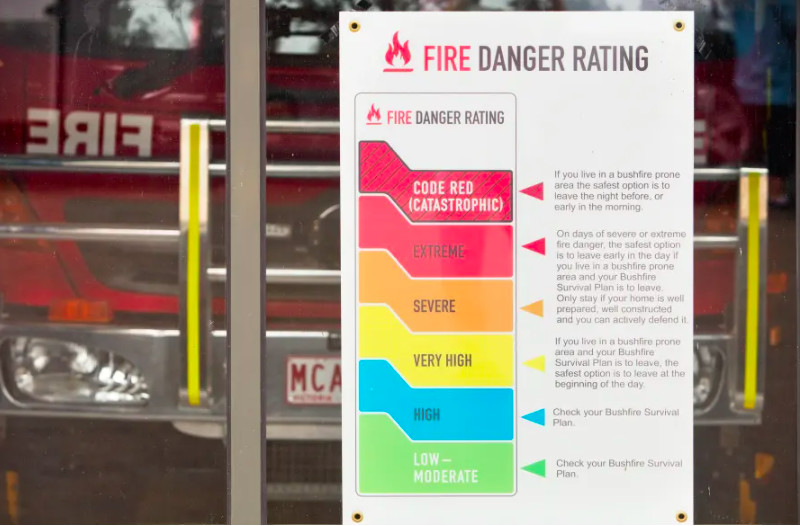

The relatively recently introduced Australian Standard Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) ratings hope to have similar benefits – although it’s still really too early to tell.

The National Construction Code requires houses in Queensland to meet minimum structural requirements which, ironically, include the ability to withstand flotation.

Regulation like this will save lives but will not avert the destruction seen in the recent Queensland floods between 2021 – 2022 that resulted in 66 of Queensland’s 77 local government areas (LGAs) activated for funding assistance under the Commonwealth Disaster Recovery Funding Arrangements (DRFA) following nine significant natural disaster events.

In response to increasing events and risk, the Australian finance corporation, Suncorp, with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), developed the One House to showcase innovative design features to address a range of extreme weather impacts.

Examples of the practical design tips from the One House example include:

• Installing electrical wiring in the roof to prevent loss of power during a flood event.

• Specify PVC plastic gutter fixings: In the event of a fire, these fixings melt and the gutters become ‘sacrificial’ and safely fall away from the house

• Consider cyclone-rated roof fixings, which are less likely to fail during extreme events with strong winds.

What’s next

Currently, much of the current focus in house design has rightly been to address the impact of our built environment on climate change– adapting to a future that includes sea level rise, increased temperatures and to counter a building’s energy impact on the environment.

But we also need to recognise that extreme weather is happening right now – so we must also now design for the impact that the environment has on buildings.

Building design for extreme weather requires a transition from a sole focus on the mitigation against long-term climate changes to addressing structural integrity, protecting human life and preservation of buildings.

Importantly, this type of design will also reduce further environmental and economic impact.

Regulations like cyclone building regulations in the Northern Territory and the Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) rating have real and immediate and meaningful impacts for new houses.

These regulations address human safety primarily via building structural resilience, with additional consideration of emergency management, communication and evacuation – equally if not more critical requirements.

Governments and insurance providers are now also weighing in. The cost and risk alone provide ample justification for their involvement, with increasingly difficult options for insurance as these events continue and get worse.

As a result, building designers must consider extreme weather impacts of their designs, including future and current impacts of climate change, rapidly evolving regulatory requirements, site-specific insurance limitations and the expectations of clients.

Banner: Flooded houses in, 2022 in Coraki, Australia/Getty Images