Designing-in difference

Culturally inclusive urban design can help shape our everyday public spaces, encouraging a vibrant multicultural social fabric here in Melbourne

Published 7 May 2021

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia came with a corresponding spike in racist behaviour towards people of Chinese – or even more broadly Asian – background.

Unsurprisingly, as places where multiple people from different backgrounds converge, racist and discriminatory behaviour happens most commonly in public spaces.

But these spaces – our streets, malls, transport hubs and parks – also offer significant possibilities for intercultural mixing .

This can encourage respect for socio-cultural differences and diversity by the sharing and shaping of our everyday spaces.

And help contribute to a vibrant multicultural social fabric, open to anyone and everyone.

SUBURBS SHAPING MELBOURNE

Our research aimed to get a deeper, evidence-based understanding of how public space design, planning and management can help to shape migrant belonging and encourage interaction between different groups of people.

Our team focused on Oakleigh – a suburb 15 kilometres south-east of Melbourne’s CBD.

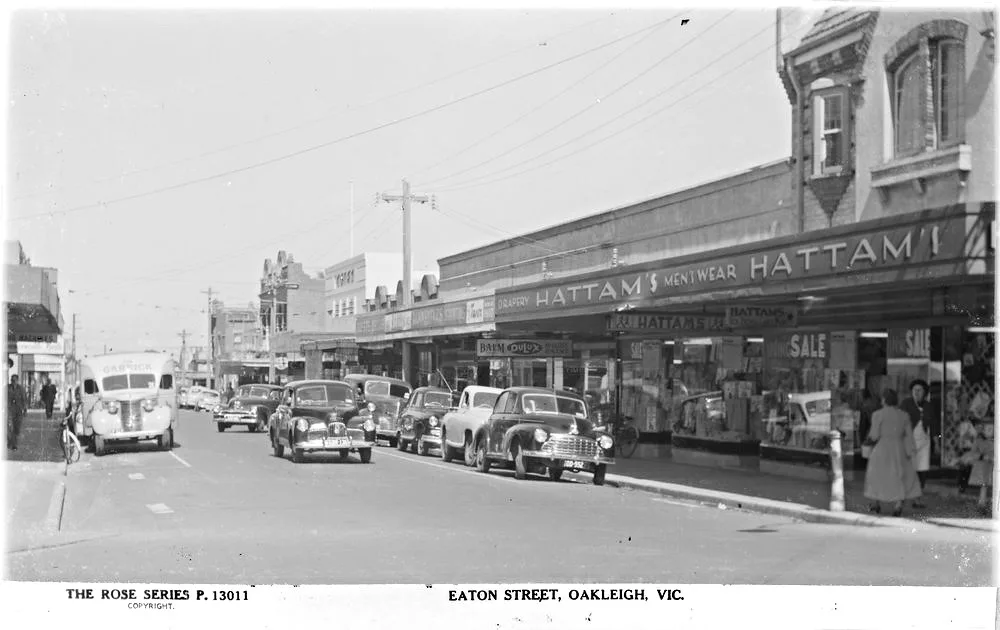

Australia’s post-war migration policies brought war refugees from Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Ukraine, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the former Yugoslavia; but also encouraged immigrants from Malta, the Netherlands and Greece to start a new life in the Lucky Country.

Many of these migrants chose to settle in areas where people from their home country already lived or that were relatively close to government-provided temporary hostels or their first place of accommodation.

As a result, ethnic clusters sprung up in several suburbs around Melbourne including Brunswick, Coburg, Thornbury and Oakleigh.

Many migrants lived in Oakleigh because the migrant hostel accommodation at Holmesglen (in the 1950s) and then Westall (in the 1970s) was nearby, which was provided by the Housing Commission of Victoria at the time.

But it also attracted ‘new’ Australians – particularly craftsmen and labourers – because of the development of the new industry employment.

Over the years, Oakleigh became what was often described as ‘the epicentre’ of the Greek-Australian community here, due in part to the Mediterranean character of many of the retail outlets, cafes and high streets in the area – although it is a multilayered ethnic landscape.

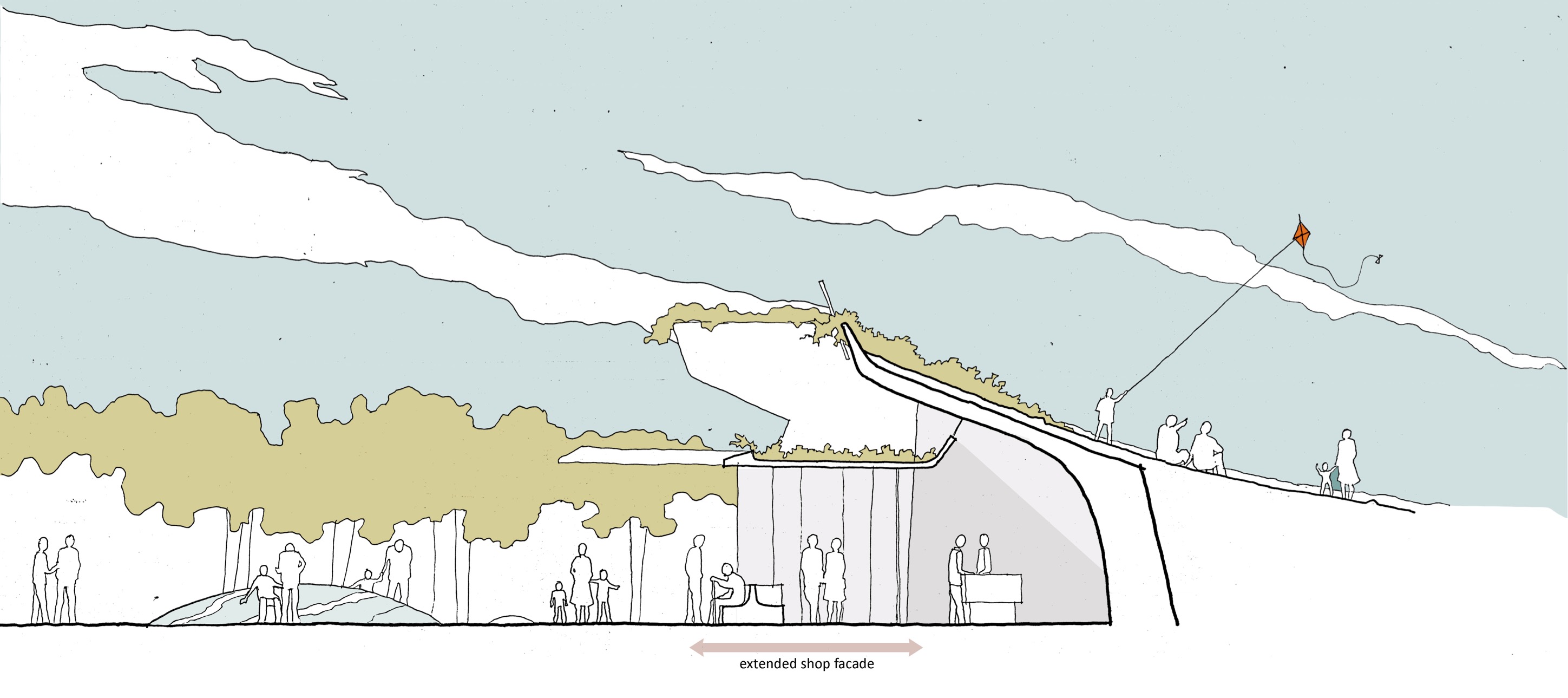

Our study looks specifically at Eaton Mall, which was originally Oakleigh’s high street, but has since been upgraded to a pedestrian mall that celebrates the suburb’s Greek cultural influence.

SOCIAL NETWORKS AND PUBLIC SPACES

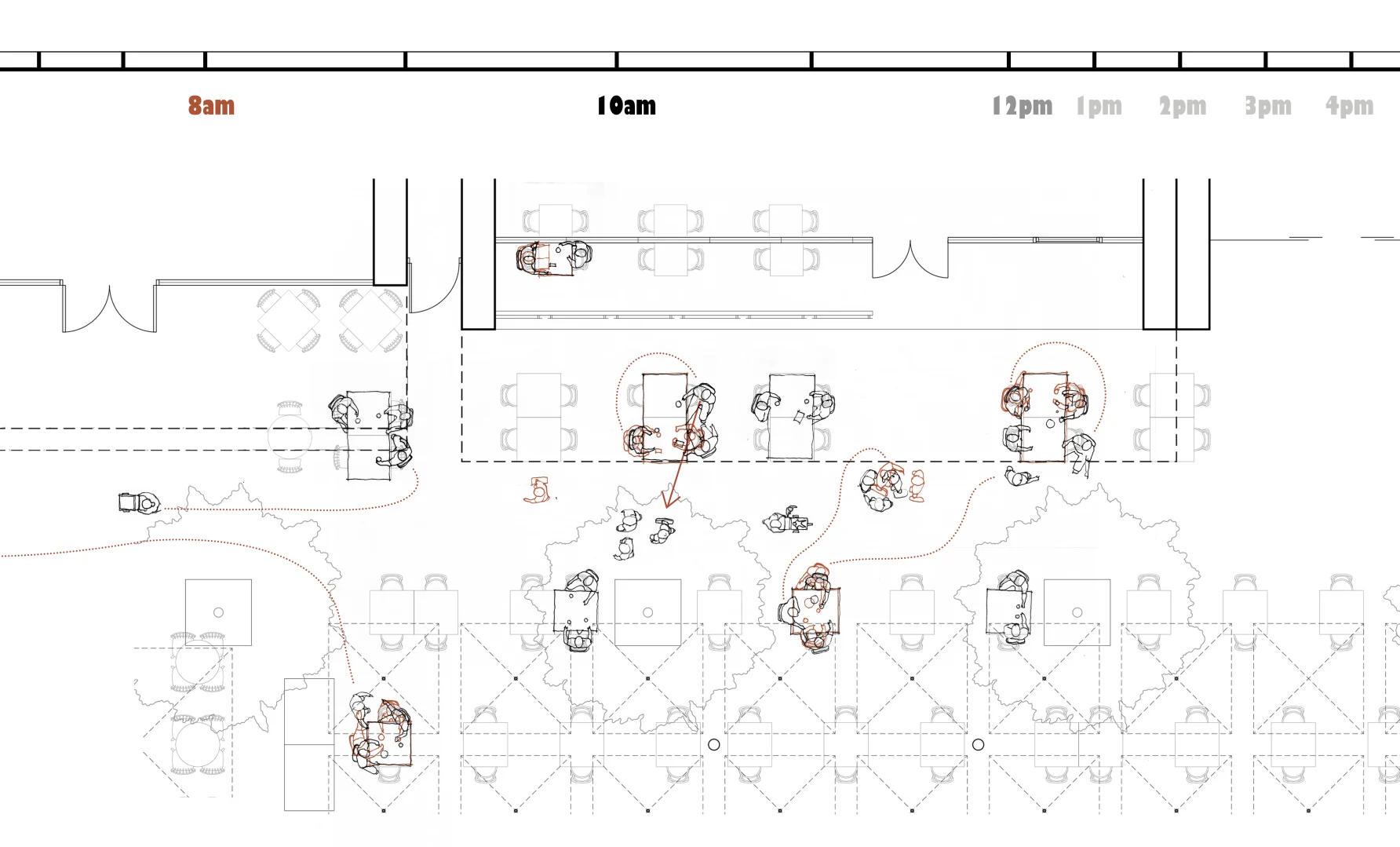

In early 2021, we used time-based mapping, ethnographic methods and interviews to better understand the way people use Eaton Mall and explore how the built environment can support that.

We found that older men, typically in groups of three to five, socialise in a distinct way at the Mall.

These groups spend their time from around nine in the morning until midday moving from one café to the next, from table to table and group to group.

Politics & Society

A not-so silent night

It appears that the concentration and formation of shops and cafes next to each other allow these men to enjoy the space this way.

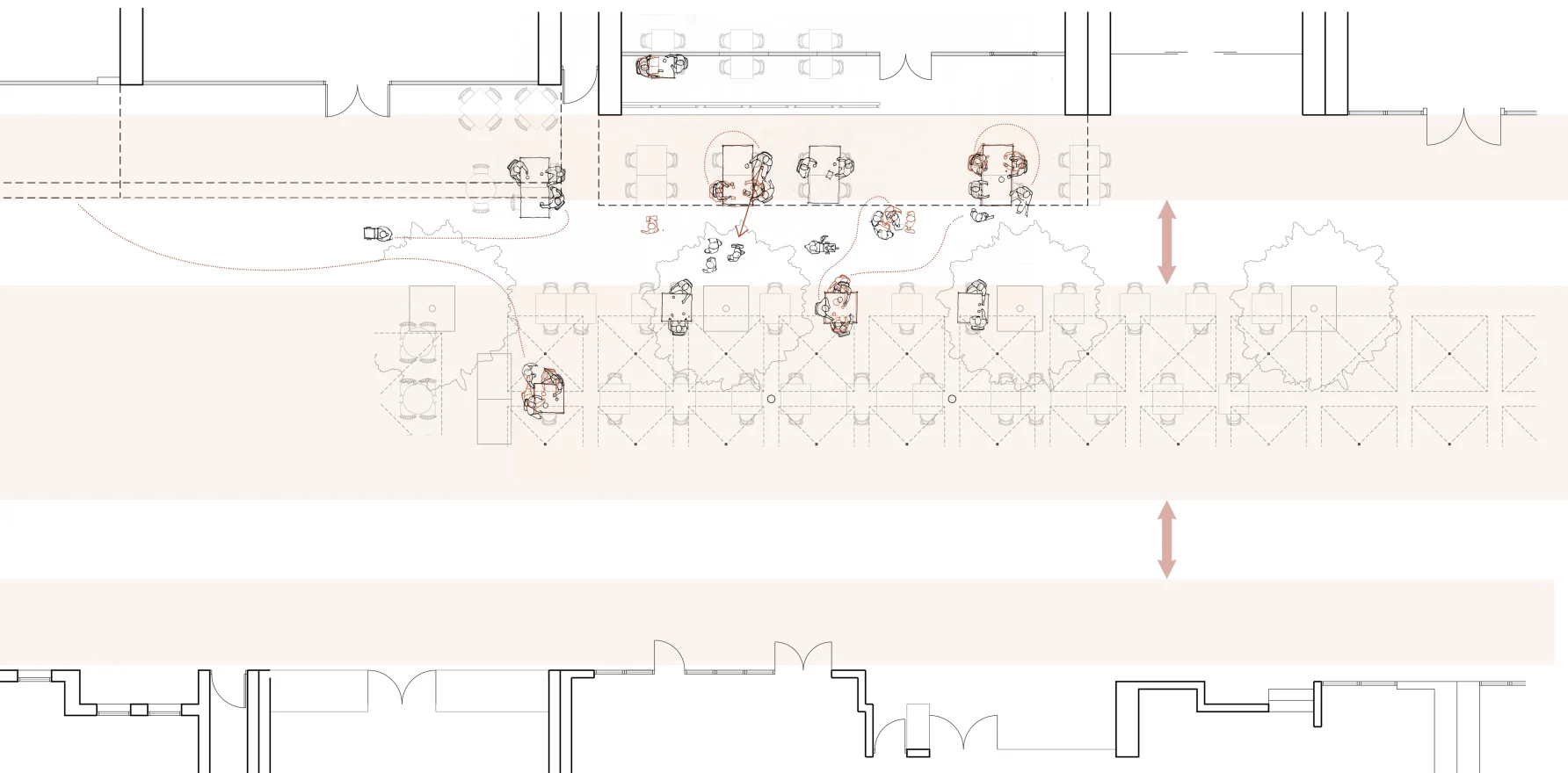

Meanwhile, the layout of two pedestrian pathways flanked by banks of tables and chairs encourages people to promenade. Being seated on either side provides a good view, as the men appear to shift seats and position themselves for better visibility of people passing by.

This close proximity allows them to recognise and call out to acquaintances who stop and step aside to chat.

While these open areas in the central bank of tables and chairs mean you are seen as much as you can see other people, there are other spaces that people have more control over; private interior spaces inside the cafes as well as shaded semi-public spaces defined by overhangs and, at times, by drop-down plastic transparent sheets.

During the six interviews we conducted with mainly first and second-generation Greek Australians visiting to the Mall, it became apparent just how important it is for older generations who use this space to maintain their social networks.

This includes the shop owners as well, and perhaps surprisingly, new migrants who rely on these networks for essential information and job opportunities.

Arts & Culture

Reframing the ‘Australian Ugliness’

But throughout the day, the way people use the Mall pivots. In the morning, there are more of these inward-facing activities, but later in the day, it becomes more outward facing –welcoming a more diverse mix of people.

Older men no longer dominate the space as more family groups and a mix of genders begin to arrive and tables are joined together to accommodate larger groups.

Even the soundscape of the Mall changes, from the mostly Greek music played by shops during the day to street performers like a string duo playing classical music or jazz musicians playing jazz walking up and down the Mall in the early evening.

MULTICULTURALISM AND PLACE-MAKING

In urban design, placemaking is the process through which we can work together to shape our public spaces.

Informal placemaking in public spaces – or the socio-spatial construction of place – can give us an insight into the ways that migrants adjust to Australian society.

By understanding places like Eaton Mall, we can in turn understand the spatial underpinnings of difference better. It can help urban design re-imagine diversity in public places.

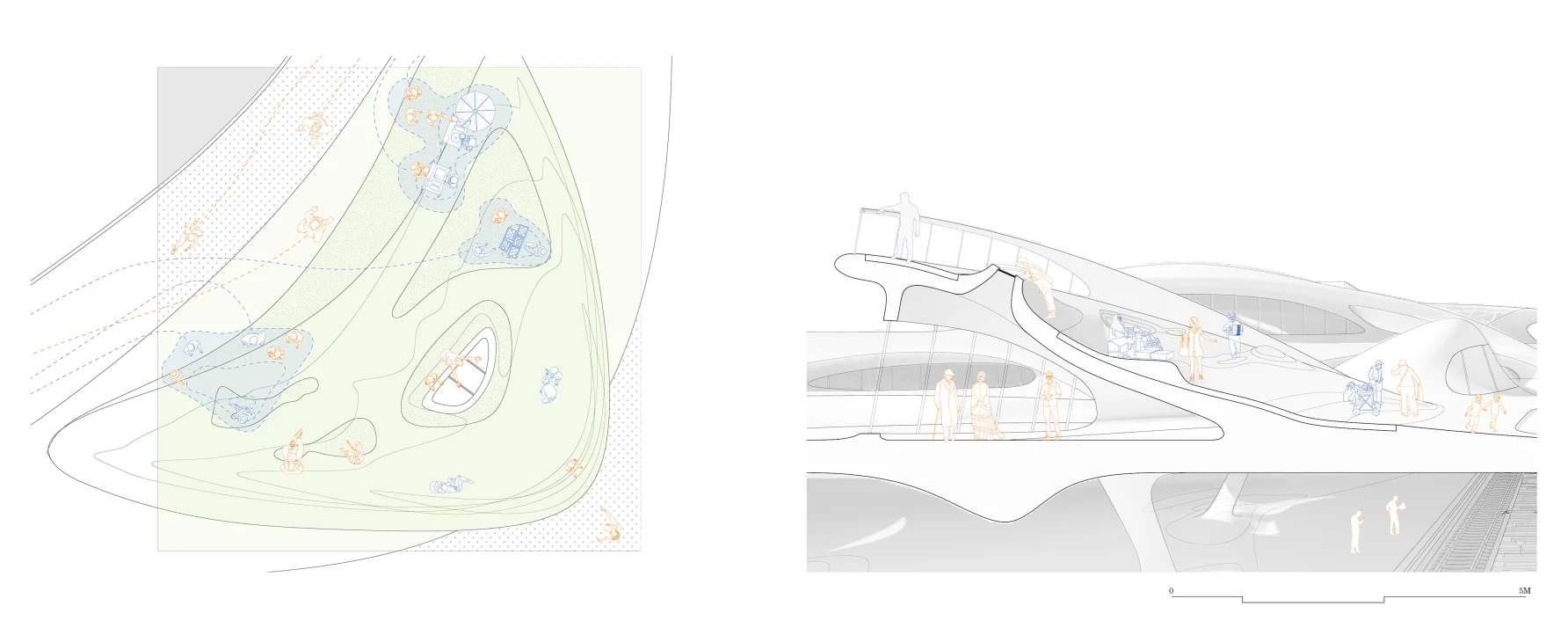

This includes designing a nuanced interface between the public and private realms, accommodating commerce at multiple scales and levels of formality, as well as built structures that allow for multiple uses.

Innovative spatial intersections with formal service providers – like Centrelink and language services – can help capitalise on informal social networks of immigrants. As well as creating complex uses for spaces through the temporary and temporal use of space.

We want to explore ways of integrating positive diversity in public space design. Although we are focusing on cultural behaviours and socio-spatial practices familiar to migrants – other important questions remain.

When it comes to our public spaces, can urban designers incorporate the complexities of cultural spaces – including internal differences, conflicts and exclusions? And to what extent can design contribute to re-framing public space as a shared resource for intercultural co-existence?

Through the embedding and, ultimately, mainstreaming of culturally inclusive practices within design there’s a chance to foster the urban design of our public spaces for a shared urban multiculturalism to flourish.