Politics & Society

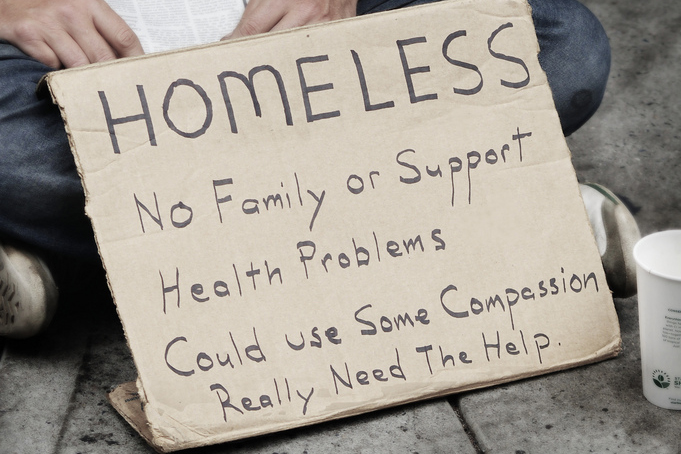

Homelessness in the World’s Most Liveable city

As disadvantaged Australians face rising housing costs, University of Melbourne research looks at the statistics that make the link between family breakdown and homelessness

Published 1 June 2017

Australia is going through a well-documented housing affordability crisis and single parents are especially vulnerable to rising housing costs, relying on one income to provide a decent home for their family.

Past research has found that “in 2013-14, 46 per cent of… low-income couple families and 67 per cent of one-parent families with dependent children in private rental housing paid more than 30 per cent of their income on rent” putting them at risk of “housing affordability stress”.

The financial pressure on single-parent households increased again in April when the Social Services Legislation Amendment Bill, which freezes or reduces entitlements to a number of family benefits, was passed by both Houses.

Taken together, rising housing costs and diminishing family benefits are putting low-income Australian families, especially those that breakdown, at risk of intense financial stress and housing insecurity as well as possibly homelessness.

So what happens when a low-income family unit breaks down within the context of these pressures?

Politics & Society

Homelessness in the World’s Most Liveable city

As part of my research, alongside Professor Jan van Ours from the Erasmus University in Rotterdam, we analysed the effect of parental separation on homelessness using a unique survey of 1,700 disadvantaged Australians who were either homeless or at high risk of homelessness. In Journeys Home we found that parental separation does indeed increase the likelihood of becoming homeless.

In this study, we used a broad characterisation of homelessness which seeks to identify situations in which families’ housing conditions do not meet standard requirements to qualify as a ‘home’.

This is qualitatively similar to the definition used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics where homelessness is defined as sleeping rough or squatting in abandoned buildings, staying with relatives or friends temporarily with no alternative, staying in a caravan park, boarding house, hotel or crisis accommodation.

Parental separation can lead to homelessness in many ways. For example, a separation might necessitate an urgent move, thereby generating a negative financial shock. Without enough savings or networks of family and friends to help cover this unexpected expense, low-income parents may be unable to afford secure and safe housing for their family, eventually leading to homelessness.

Even less disadvantaged parents, who may be able to cope financially in the short run (such as by covering housing costs with their savings for example), may be unable to do so in the medium term once those savings have run out, becoming homeless a few years after the separation occurred. Parental separations can also create conflict between parents and children, which may drive children out of their parent’s home and potentially into homelessness in subsequent years.

In the Journeys Home sample, family breakdown indeed appears to be an important trigger for homelessness. Of those who have experienced homelessness, 62 per cent of respondents cite family breakdown or conflict as the main reason for becoming homeless for the first time.

However, the research linking parental separation and homelessness is scarce because most available datasets are not well suited to this purpose. Disadvantaged populations that have experienced homelessness are underrepresented in general household surveys; and datasets which only include people who are currently homeless fail to capture other segments of the disadvantaged population who might be at risk of homelessness.

Politics & Society

Homeless: Why making it a crime won’t fix the problem

In contrast, Journeys Home is unique in that it covers a broad spectrum of the disadvantaged population, not just those currently homeless. In fact, 75 per cent of respondents were not homeless at the time of the first interview. At the same time, the high frequency of homelessness and parental separation in the sample provides enough occurrences to address the question of a potential causal relationship between the two.

Our research exploits the detailed information in Journeys Home on respondents’ histories to investigate whether their parents’ separation (if ever) led to their first experience of homelessness (if ever).

We found that parental separation increases the likelihood of becoming homelessness, conditional on observed and unobserved (family and individual) characteristics.

The effect is substantial: if parents separate before the child reaches age 12, boys have a 10-15 percentage point greater chance of becoming homeless by age 30. In girls, there’s a 15 -20 percentage point greater chance of becoming homeless by age 30. However, if the parental separation occurs from the age of 12, the effect only persists for boys, who are at greater risk of becoming homeless.

The effects on homelessness are larger when the parents were formally married prior to the separation.

Our results constitute a critical first step in understanding how individuals, and in particular children or young adults, become homeless. It highlights the role that parental separation can play in the process of a person becoming homeless, and therefore the pressing need to address the issue of housing affordability for disadvantaged families that breakdown in order to protect children from poverty and homelessness.

If you or anyone you know needs help, you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

A version of this article also appears on The Conversation.

Banner: Stephen Lilley/Flickr.