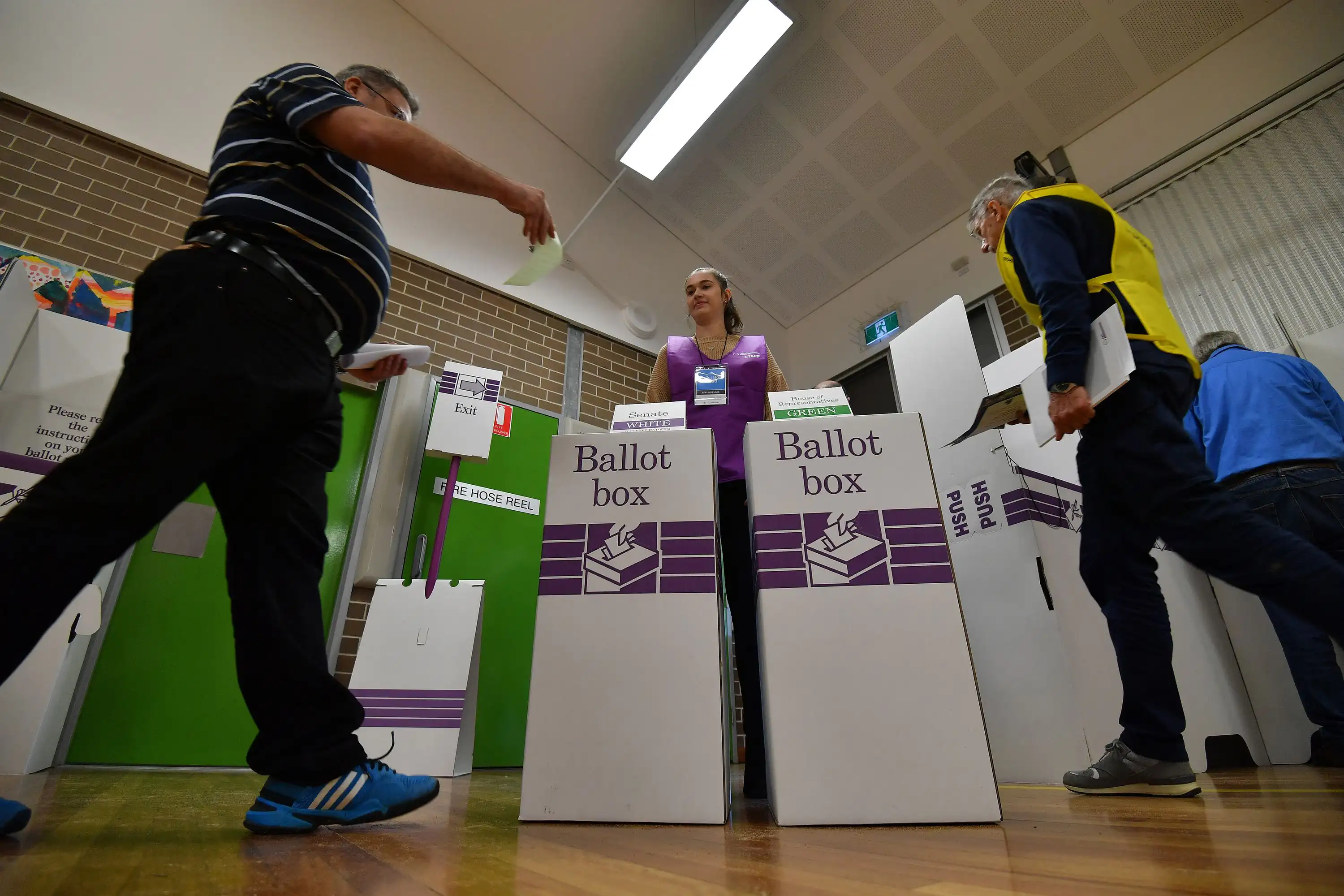

Disinformation damages democracy, but perhaps not in the way you think

Many Australians are aware of the influence of misinformation and disinformation on elections, but there are more insidious ways it harms our democratic society

Published 15 April 2025

Australia is heading to the polls on 3 May, and as we enter the campaign, the amount of misinformation we are exposed to is likely to increase.

Some of this misinformation is deliberately designed to deceive us. This type of misinformation is typically referred to as ‘disinformation’.

Disinformation is likely to have long-term detrimental effects – but probably not in the way you think.

Disinformation campaigns attempt to convince the audience of something that is not true. These kinds of campaigns are organised and systematic – much like conventional advertising campaigns.

We know a lot about conventional advertising campaigns as they’re very well studied. We also know they’re highly effective, at least at the population level, and that’s why globally over US$1 trillion was spent on advertising in 2024.

Disinformation campaigns are likely to be similarly effective.

But demonstrating this is difficult due to ethical and legal concerns: no ethics committee is going to allow the intentional dissemination of misinformation or disinformation to study how it affects democratic outcomes.

Consequently, the studies of the effectiveness of disinformation campaigns are indirect and correlational, which limits any conclusions they can draw.

The evidence we have suggests that disinformation campaigns can create small but significant shifts in public opinion. These are potentially enough to tip the balance in a close election.

But even the threat that a disinformation campaign can affect an electoral outcome can be enough to have an election nullified.

This happened in 2024 during the Romanian presidential election.

The threat to democratic institutions is one of the many reasons why in 2024, the World Economic Forum labelled misinformation and disinformation the greatest short-term global risk.

The greater dangers of disinformation

While small shifts in public opinion can influence elections, the greatest danger is how misinformation and disinformation can change our dominant narratives.

Our societal narratives are much more important than you might think – and can cause real harm.

For instance, there’s no logical reason to suspect that 5G towers could cause COVID-19. In fact, there’s no reason to believe that these towers cause any harm at all.

But a widespread narrative alleging that 5G towers are harmful has resulted in multiple cases of vandalism that have put lives at risk.

If we look at another example – vaccine refusal – the potential for harm is much greater.

For instance, between 30 May 2021 and 3 September 2022 there were at least 232,000 deaths in the US caused by COVID-19 vaccine refusal.

To put that number into some perspective – that’s more deaths than the number of US military fatalities in World War I, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War and in the War on Terror combined.

As these examples show, misinformation and disinformation can cause immense harm by undermining trust in science through their impact on public narratives.

Sometimes these anti-science narratives are created by companies for financial reasons.

The PR firm Hill & Knowlton famously advised tobacco companies to fight the growing science that tobacco was harmful by creating doubt, rather than outright denying it.

By sponsoring ‘scientific’ studies that disputed the harm caused by tobacco, and by mounting large-scale advertising campaigns to sow doubt, Big Tobacco delayed legislation for years – boosting their profits but causing a vast number of avoidable deaths.

Inspired by this ‘success’, other industries adopted the same playbook.

The fossil fuel industry funded disinformation campaigns to cast doubt on the connection between human activity and climate change.

Major chemical companies funded disinformation campaigns to cast doubt on the connection between pesticides and the environment.

Politics & Society

Your social media feed is changing democracy

Major pharmaceutical companies funded disinformation campaigns to downplay the risks of addiction.

And politics is not immune.

This denial of factual evidence is something we can expect to see in Australia’s federal election, where it’s likely to gain prominence through the major parties’ official campaigns.

In fact, we’ve already seen it. One of the big debates in Australia right now is about energy. Several politicians have been promoting nuclear energy as a viable, cheap alternative.

This is despite a report from Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, which found that nuclear power was still about 50 per cent more expensive than renewables – even after it changed its modelling to accommodate criticism.

Similarly, in the US, we’re seeing renewed attacks from the new administration on the scientific basis of vaccines. When the science is provided, it’s dismissed.

And it’s a trend that’s made its way to Australia.

Victoria is already battling a measles outbreak as a result of vaccination rates dropping below the 95 per cent national target since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Questioning facts

An effective way to raise doubt in scientific research is to repeatedly and publicly question it. Now, science should be questioned – but to add to scientific inquiry, those questions must be objective, and they must be testable.

If a statement is repeatedly made, especially by an authority figure, people will begin to believe it – the so-called illusory truth effect.

If scientific evidence is repeatedly questioned (without basis), people will begin to doubt it, regardless of whether there is any rational reason to do so.

The media often contribute by trying to give equal time to both sides of an argument, even if one side is not supported by robust evidence.

For instance, by repeatedly inviting climate change sceptics to debate climate change with scientists, the media contributed to casting doubt about the origins of climate change – something the scientific community is still wrangling with today.

As the advertising industry knows, we tend to believe what we repeatedly hear. That is why disinformation campaigns are so dangerous.

During the upcoming federal election, Australians are going to have misinformation and disinformation repeated to them. As a result, some people will end up doubting the science that contradicts it.

This, in turn, can affect their subsequent beliefs and how they interact with each other.

And that may be the biggest consequence of disinformation in the upcoming federal election – a less rational and cohesive Australia, influenced by information that's been manipulated to make us believe it.

Associate Professor Piers Howe carries out paid research for the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet into misinformation and disinformation.