Health & Medicine

COVID-19 and cancer care

Patients with blood cancer – including leukaemia, myeloma, and lymphoma – experience higher psychological distress from risk of COVID-19 infection and unmet needs, finds new research

Published 5 July 2021

Over a year into the pandemic, we have all felt the effects at this point. But the disruptions and stress haven’t been spread evenly across the population and the health effects are often broader than first recognised.

For over 110,000 people in Australia living with blood cancer – including leukaemia, myeloma, and lymphoma – the challenges they already face have been exacerbated during the pandemic.

Every day, 47 Australians are newly diagnosed with blood cancers. As a life-threatening illness, a blood cancer diagnosis can produce significant levels of psychological distress for both patients and their loved ones. Now the COVID-19 pandemic has only heightened this distress.

Health & Medicine

COVID-19 and cancer care

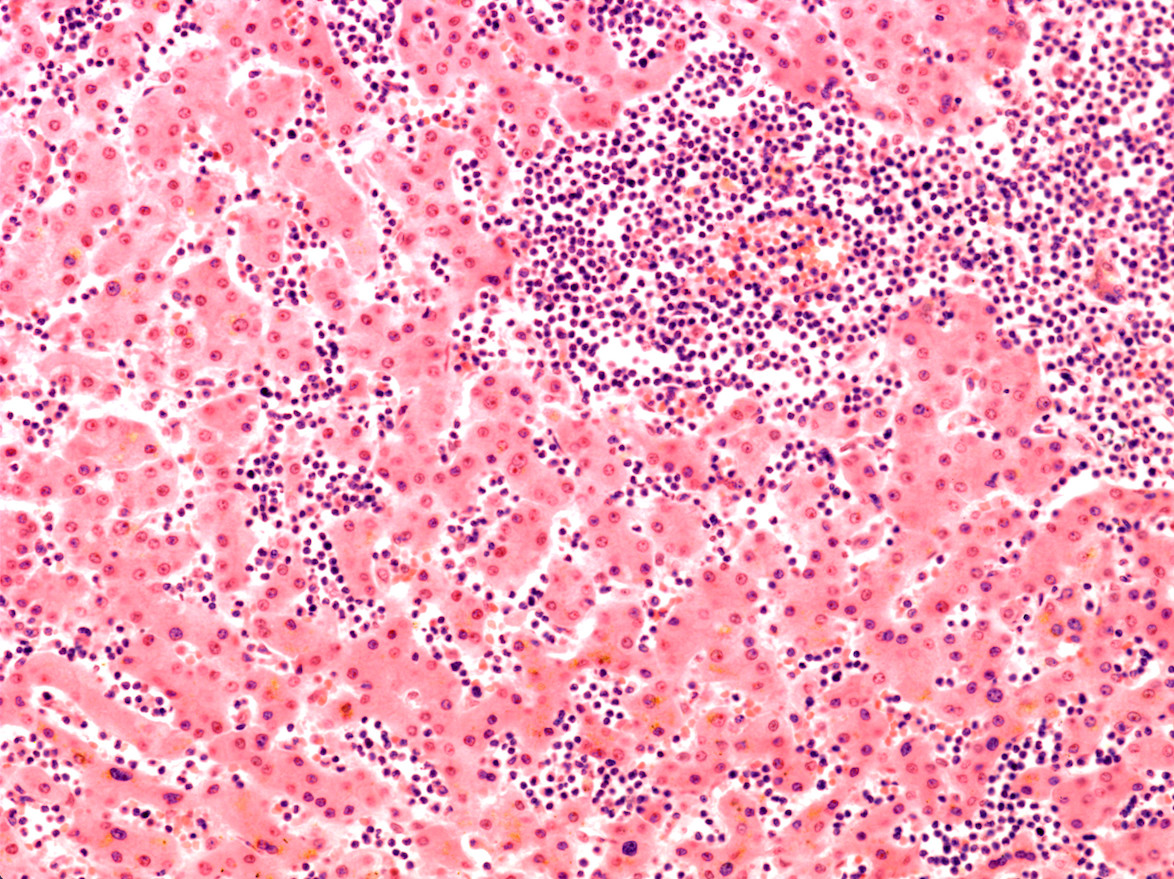

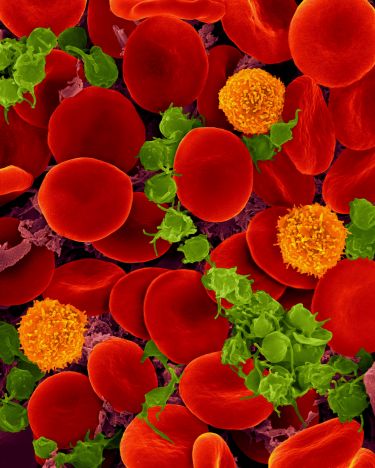

People living with blood cancer are a particularly vulnerable subgroup of cancer patients because these diseases begin in the blood cells of the immune system, the very cells that we normally rely on to fight off infection.

Produced in the bone marrow, these immune cells are usually reduced both in their overall number and their ability to function by cancer. Some medications used to treat cancer can also weaken the immune system for an extended period.

Consequently, these patients are amongst the most vulnerable in the community of both acquiring COVID-19 and death when infected with the virus.

A recent meta-analysis, which combined and analysed data from multiple previous studies, looked at 3377 patients from three continents and found a mortality risk of 34 per cent among people with blood cancer and COVID-19. When compared with a mortality rate of less than 5 per cent among the average population aged 75, these results emphasise the vulnerability of those living with these diseases.

This risk is leaving many blood cancer patients feeling uncertain and anxious; and it is impacting their everyday lives, posing questions like - Is it safe to undergo immunosuppressive treatment, given the risks of coronavirus? Do the risks of getting the virus outweigh the benefits of seeing loved ones, or even going to work?

Health & Medicine

Is a delayed cancer diagnosis a consequence of COVID-19?

Back in March 2020, we were deeply worried about the psychological effect that this pandemic would have on people living with blood cancer. Not just for a few weeks, but for months and potentially even years.

So we got together as a team over Zoom and decided to set up a new project, surveying and interviewing Australians living with blood cancer across the country about their wellbeing.

Nearly 400 Australians living with blood cancer participated in our survey study. The results, published in the journal Supportive Care in Cancer, found that patients reported a high psychological burden during the pandemic. Most concerning was the finding that psychological distress scores had doubled compared to previous studies involving Australian blood cancer patients during non-pandemic-times.

Similar results were observed for unmet supportive care needs. Among respondents who had finished treatment and were in remission, fear or worry that their cancer could return or progress was reported by nearly all.

Key findings from this study include:

At least 1 in 3 (35 per cent) reported experiencing clinically significant psychological distress, up from 17 per cent for patients with the same conditions before the pandemic

Education

The psychology of isolation

At least 1 in 4 (28 per cent) reported they had unmet health system and information needs during the pandemic, up from 20 per cent for patients with the same conditions before the pandemic

Nearly 1 in 4 (24 per cent) had unmet care and support needs during the pandemic, up from 10 per cent for patients with the same conditions before the pandemic

Nearly all (95 per cent) respondents who had finished treatment and were in remission reported clinically significant fear of their cancer returning or progressing

Patients who were younger had financial concerns or were worried about contracting COVID-19 reported higher distress

Patients who had lost income due to lockdown measures, were worried about contracting COVID-19 or who didn’t feel adequately supported by their care team reported higher unmet needs

Patients who were concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on their cancer management reported higher fear of their cancer returning or progressing

Strategies like social distancing, quarantine, and visitor limitations provide important protection for people living with blood cancer. But they also limit opportunities for social support and income generation.

Health & Medicine

New test to improve blood cancer treatment

Importantly, opportunities to connect with others and earn an income might not return for some time, as the consequences of potential exposure to the virus by having visitors, attending restaurants, or returning to work may be perceived as too great of a risk.

Our results also shed light on the reported declines in patients attending clinical appointments during the pandemic. The high rates of fear of cancer returning or progressing may reflect the changes and disruptions to care and reduced contact with their care team.

With fewer face-to-face appointments, patients miss out on the valuable information, reassurance, and emotional support provided by their care team, thereby heightening distress, worries about their cancer returning, and increasing the need for supportive care.

The psychological burden noted by blood cancer patients in the survey provides new urgency for remote screening tools that can rapidly identify distress and unmet needs during crisis times when face-to-face care is limited and there is increased pressure on service delivery.

While it’s important to acknowledge that some distress during this challenging time is normal, we need to identify and respond to those experiencing severe distress.

Health & Medicine

How your blood can help understand COVID-19 vaccine responses

The distress thermometer provides a simple remote screening tool for clinicians to identify patients who may benefit from referral to low-cost specialised psychosocial care. Videoconferencing platforms may be particularly useful when assessing patients for distress because clinicians can respond to facial cues and body language.

As restrictions ease and we are told that life is getting back to ‘normal’ for many in the community, for people living with blood cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is no ‘return to normality’, at least not yet. Every day, they are faced with tough choices, knowing that ‘normality’ brings potentially life-threatening risks.

We need to optimise our services in response to these issues so that we are prepared for future pandemics or other crises and ensure that people living with blood cancer are provided with the support they need.

Banner: Getty Images