Politics & Society

Sexism, women and Australian politics

A lack of understanding of women’s fear in public spaces still puts the burden of personal safety on the victim, not the perpetrator

Published 6 March 2022

It takes a lot of courage for a person – whether they’re female or male – to stand up and talk about any experience of sexual harassment. And yes, people are listening now, but are we learning and safeguarding for the future?

Here in Australia, the spotlight has been on parliament and our political system as more and more women come forward to speak their truth – whether it’s parliamentary staffers exposing sexual harassment or women in political offices revealing the “toxic workplace culture” that still exists in our country.

These reports expose the nasty underbelly of some of our private spaces – our offices and workplaces.

But to properly tackle this issue effectively, we need a more proactive approach when it comes to understanding people’s experiences of harassment or assault – particularly in our public spaces.

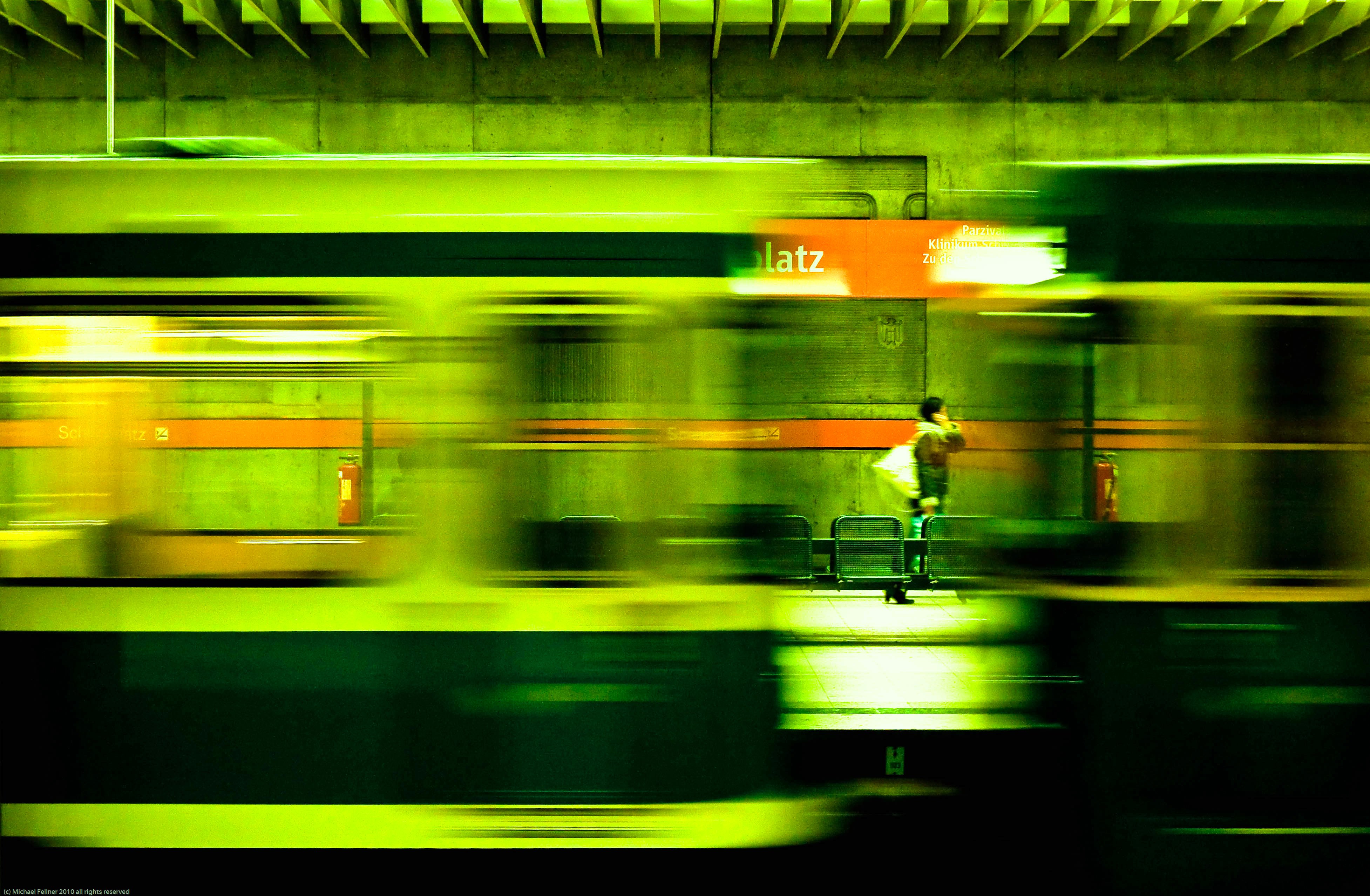

Sexual harassment and assault often happen in places familiar to the victims – in their own homes, the places they work or study. But sexual harassment and assault also happens in public – on public transport and public spaces nearby.

Politics & Society

Sexism, women and Australian politics

Our recent research aims to understand the nature of sexual harassment and victimisation that’s happening in public. Especially on public transport.

We surveyed 1,000 college students across three Southeast Asian cities – Cagayan de Oro City in the Philippines, Pathum Thani City in Thailand and Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam – to get a better picture of the commuting experience for young people in these locations.

Our study showed that sexual violence and harassment on public transport or in the commuting environments nearby has been on the rise for the past three years and still remains prevalent.

Three out of five students in Cagayan de Oro City, one in two students in Pathum Thani City and almost 60 per cent in Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam reported experiences of harassment. But we also found that most instances of harassment still go unreported due to the stigma that still surrounds it.

Our research starkly highlights that public transit spaces continue to be dangerous and threatening – particularly for women and girls.

As a response, women alter their travel behaviour or avoid travelling at night altogether. But this doesn’t call out the action of the perpetrator and, instead, places the burden of personal safety on women rather than on society as a whole.

Politics & Society

Prevention and justice for sexual violence

And it would be a mistake to think that these incidents aren’ happening in Australia as well.

A 2017, a United Nations Human Right’s Commission survey of 39 Australian universities showed 51 per cent of students experienced some kind of sexual assault and harassment within university settings, while one out of every four students were sexually harassed while travelling to or from university in 2016

But the reality is we still don’t have enough data for how safe people feel on public transport in Australia.

If we don’t have the knowledge about what our people experience on a day-to-day basis, how are we to build safeguards against sexual harassment or assault in public spaces?

Our current responses to sexual violence and reports of harassment are reactive. They are more of a bandaid fix than being any progress towards long-term healing.

A women-only carriage is one strategy that’s been adopted by many cities with varying success. But this kind of segregation of women and men doesn’t address the root of the problem – a lack of understanding of women’s perceptions of fear and safety in public spaces.

So it allows the continued perpetuation of sexual violence in public transit.

Politics & Society

Busting the myths about sexual harassment

Having a clear understanding of the experiences of people is an important step towards creating policies and spaces that pave the way for healing and not cause any further harm.

There are some commendable steps out there heading in the right direction.

Free to Be, a crowd-mapping tool developed by Plan International Australia and Monash University’s XYX Lab, aim to identify happy and sad (or safe and unsafe) places. SafetiPin is a mobile app that’s working with government to make Indian cities more inclusive, while another project re-imagines Barcelona as if it were built by women for women.

Listening is the first crucial step prior to any kind of response.

An online petition in Australia collected the testimonies of students who experienced sexual assault harassment while at school. It went viral. This tells us that survivors are willing to report these crimes if an anonymous platform is available for them to do so.

But knowing how and when to respond to this disclosure – while also providing immediate support and comfort – are vital to providing a safe and empowering spaces that also open up the conversation for meaningful healing.

Health & Medicine

Sexual objectification harms women

In 2020, the United Nations celebrated a decade of the Women’s Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces Global Initiative. This initiative was first implemented to prevent and respond to sexual harassment and other forms of sexual violence that women and girls often experience and fear in public spaces.

But even now, violence against women and girls remains one of the most prevalent human rights violations in modern society.

This International Women’s Day, it’s important to focus on how we think about our public spaces, our public transport and our transit spaces that doesn’t put the onus on women and girls to alter their behaviour because they’re afraid. This could be just one of the steps in the right societal direction.

Banner: Shutterstock