Politics & Society

Four reasons to watch the Dutch Election

The predicted lurch to the far Right has not materialised

Published 16 March 2017

The Dutch elections have produced a bittersweet victory for centre-right incumbent Prime Minister Mark Rutte and his VVD Party.

With over 90 per cent of the vote counted, it’s clear the VVD will become the biggest party with a significant lead: potentially 33 seats out of 150. It’s likely that the threat of major gains for the Party for Freedom (PVV) – the party of anti-Islam, anti-European Union Geert Wilders - helped consolidate votes for the Prime Minister.

But Rutte’s apparent victory is also a loss, because the VVD is eight seats down from the previous election. And it is far from clear whether and how Rutte is going to form a majority government.

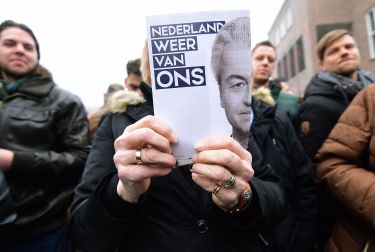

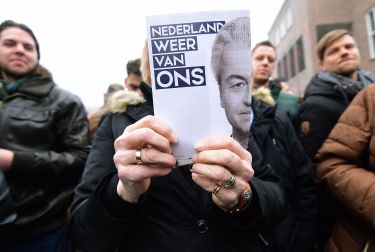

Wilders and his Party for Freedom made some headway, but it’s not the landslide thought possible from his strong standing in opinion polls. The party is likely to become the second biggest, growing from 15 to 20 seats.

With his outspoken views, and a haircut and a Twitter repertoire reminiscent of US President Donald Trump, Wilders dominated much of the international news coverage during the campaign. But we now know this election has not produced his rise to power.

Wilders has been a steady force in Dutch politics for over a decade. His party is a major player, but with all other parties turning their back on the Party for Freedom, it is very unlikely Wilders will have his hand anywhere near the levers of power.

There has been speculation of a Dutch exit from the EU, but the popular support for a ‘Nexit’ consistently hovers between just 15 per cent and 30 per cent, which is among the highest in Europe.

The Dutch know they are not Britain. They have no imperial illusions, they have no Commonwealth, and they have an economy that is thoroughly integrated with the European market.

With the entire political centre splintered across several medium-sized parties, the only viable government will be a broad-based rainbow coalition. It will be a government of compromise and middle ground. A government that will implement policies after endless multi-party consultations. A government that may take until Christmas to even be formed.

Politics & Society

Four reasons to watch the Dutch Election

The collapse of the famous Dutch system of polarised politics has finally come to a head. The big political streams of liberalism, social-democracy and Christian-democracy have disintegrated. The three pillars that used to make up the entire mainstream political spectrum now have about 60 out of the 150 seats. With its cut-and-dry political system (no electorates, no thresholds; just national parties each with one national list), political sentiments do not take long to percolate in Dutch politics. Partly for this reason, Dutch politics has at times been like a bellwether for political sentiments in Europe.

No single political sentiment has prevailed in these elections. Yes, some voters have swung to the right (mainly to Wilders), but also to the Christian Democrats (from 13 seats to a predicted 19) and we’ve seen the rise of the senior party 50+ (two seats to a predicted four seats).

But the Green Left party led by Justin Troudeau look-alike Jesse Klaver (the “Jessiah”) has rocketed from four to a likely 14 seats; and its ideological brethren the Party for Animals has jumped from two to a likely five seats. The cosmopolitan and pro-European liberal democrats of D66 have gone from 12 to a likely 19 seats.

To top it all, new radical parties have entered parliament, most obviously DENK (‘think’). This party, with a likely three seats, is run by two renegade MPs with a Turkish background and uses fierce populist rhetoric to accuse the entire political elite of being racist.

So much for the rift between people and politics. So much for the right-wing anti-globalist sweeping one country after the other. A wide diversity of issues and perspectives prevailed in the campaign.

Politics & Society

Liberal Democracy: Why we may be losing it

In fact, organising debates with ten or more party leaders started to become a political challenge. A dazzling diversity of issues was debated: hard-line Turkish populism and anti-racism slogans; earthquakes in the gas fields of the north; leftist calls for animal rights; ground-breaking tax reforms driven by ecological ambitions; nationalist calls to reintroduce singing the national anthem at elementary schools; and calls for further expanding the laws on euthanasia. There has not been a lack of diversity. And looking at the electoral outcome, the new parliament reflects this diversity.

In some ways, this is great news for democracy. People are being heard. The question is: how can Prime Minister Rutte form a government with a coherent agenda with four or even five parties’ wildly divergent agendas?

Getting the VVD, Christian Democrats (CDA) and Liberal Democrats (D66) to shed the rivalries of campaigning and join hands is business-as-usual in a country with a long history of coalition politics. But this time, it’s really down to the wire. By the latest estimates, such an alliance would be a few seats short of the 76 needed for a majority. With the Christian Union (a likely five seats), such a coalition would just have the necessary numbers by the latest count, but a one-seat margin is hardly a solid basis for government in country where renegade factions have become a normal part of politics.

What about striking a bargain with a party further to the left? Labour (PVDA) have experienced an electoral avalanche (a devastating drop from 38 to an all-time low of probably just 9 seats). But the Greens have won on a ticket of breaking with the neoliberal mainstream and what they labelled the ‘nasty’ policies of the right. Both Labour and the Greens will sell their skin dearly.

Some water will have to flow through the parliamentary pool at the Inner Court, as the Dutch Parliament is known, before a majority coalition bargain crystallises.

Judging by the current polls, Emmanuel Macron has the best cards for the French presidency over the anti-EU Le Pen and Germany seems headed for a Grand Coalition of the Christian Democrat Union and the Social Democrat Party. If that happens, neither is likely to put a fuse in the European project.

So is European politics back to usual? Well no. Wilders may not have caused waves that European markets and political moderates were fearing, but the issues he advocates are not going away. Large numbers of people have voiced their concerns over migration, over radical Islam, over the Euro as common currency, and over the ability of the EU to face its geopolitical challenges with the UK pulling out and Trump casting doubt over trans-Atlantic loyalties.

It will be a major challenge for centrist governments, founded on a whole stack of compromises, to credibly address all that.

Most urgently, how are European governments going to respond to the current diplomatic crisis with Turkey?

Politics & Society

Why France is taking Europe to the crossroad

Rutte’s victory was probably helped by his tough response to Turkish attempts to campaign on Dutch soil for a Turkish referendum that would consolidate Erdogan’s power. The Turkish Foreign Minister was refused landing rights. When the Minister of Family Affairs then arrived in Rotterdam by car, she was met by heavily armed policemen who threatened to lift her car on a truck and take her out of the country. She was arrested and deported. This unleashed significant unrest. It took riot police the better half of the night to curb the crowd.

If the EU’s deal with Turkey on regulating migration from Syria and elsewhere collapses, it will have a new crisis on its hands.

Dutch politics will likely see some significant challenges and crises well before a new coalition lines up on the stairs of the King’s palace for its inauguration.

This article was co-published with the University of Melbourne’s Election Watch Europe

Banner image: Geert Wilders talks to the media on election night in The Hague, on March 15, 2017. Picture: Remko de Waal/Getty