Eating supplements cannot beat the real thing

The form that food takes when we ingest it plays a key role in how well we absorb its nutrients

Published 27 October 2015

Nutrients have a specific role in the body, but it’s how they are delivered –the “food matrix” – that affects their functionality.

The food matrix is a fascinating concept that doesn’t get much attention, but it is crucial in affecting nutrient release, and therefore the action of the nutrient in the body. The US Department of Agriculture defines it as:

The nutrient and non-nutrient components of foods and their molecular relationships, i.e. chemical bonds, to each other.

In order for a nutrient to perform a function in the body, it must first be available for absorption (that is, be “bioavailable”) in the small intestine after digestion in the stomach. However bioavailability is based on release from the food matrix (whether it is “bioaccessible”).

Cheese is a great example of how processing changes the food architectural structure, and in doing so alters nutrient actions in the body.

Previously on Pursuit, I discussed a study conducted by the University of Copenhagen, which found healthy people on calcium-rich diets produce less LDL cholesterol, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease commonly known as “bad cholesterol.”

In this study, subjects consumed either a 500mg calcium supplement or 1700mg calcium sourced from either low fat milk or cheddar cheese. Although dairy milk and cheddar cheese have saturated fats, consumption of these foods resulted in lower cholesterol production and more fat excreted in the faeces.

Surprisingly the pure calcium supplement did not have the same effect as milk and cheese, which brings us back to the role of the food matrix on nutrient absorption, and strengthens the argument of eating wholefoods than individual nutrients.

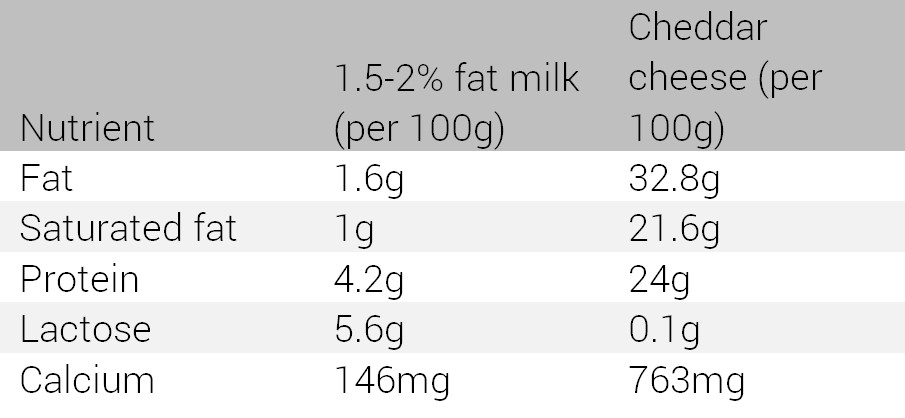

While the supplement would be considered pure (i.e. 500mg calcium), milk and cheese are both sources of calcium and other nutrients including saturated fat, protein and other minerals. However, the quantities of these nutrients are different between milk and cheese.

This is due to the different architectural structure they have: milk is in liquid form, while a semi-hard cheese like cheddar is in solid form.

Milk may seem like a simple white liquid, it is in fact a complex emulsion mixture of fat globules (i.e. small, round particles) and casein micelles (i.e. clusters containing casein protein and the minerals calcium and phosphorus) suspended in essentially water. Milk also contains dissolved lactose (milk sugar), whey proteins and other minerals.

It is relatively simple for nutrients to be absorbed from milk as it already is in liquid form rather than a solid, which requires chewing and breaking it down into small particle size.

Semi-hardhard cheese on the other hand is essentially the densely packed coagulated milk protein with entrapped fat that has been produced by enzyme spoilage.

Little miss muffet

Rennet (a proteolytic enzyme found in the calf stomach; however plant-extracted enzymes are used to make vegetarian cheese) is added to milk in order to destabilize the casein micelles out of the liquid matrix. This causes the micelles to coagulate together forming curds in which fat globules and whey is encapsulated.

This is what Little Miss Muffet would have been eating while sitting on her tuffet. However, had she followed through with the ensuing stages of hard-cheese manufacture including salting, pressing and ripening (for flavour development) forcing whey to be expelled and separated from the ripening curd, Miss Muffet would have produced a semi-hard/hard cheese.

Semi-hard/hard cheese also do not contain lactose as lactose is used as an energy source for enzymes during cheese production. As semi-hard/hard cheeses are essentially concentrated versions of milk, cheese like cheddar contains higher levels of fat, protein and calcium than milk

Therefore cheddar cheese, while containing fat, protein and calcium like liquid milk, has a very different architectural structure to liquid milk, and consequently differing nutritional composition. In essence, semi-hard cheese is a compact casein-protein and fat matrix with around 48 per cent fat content.

Calcium’s important role

Based on the understanding of food structure and the resultant cholesterol production after intake of a pure calcium supplement, liquid phase milk and a semi-hard cheese, it seems that calcium clearly has additional roles in the body than just strengthening teeth and bones and may play an important role in prevention of cardiovascular disease.

The Copenhagen study clearly shows the importance of dose intake and the form that food is consumed has on health outcomes.

Though the nutritional components of foods may be similar, processing can alter the architectural structure of food. The food matrix plays a big role in the way nutrients are released and behave in the body after dietary intake.

While supplements have a very important role in diets that lack nutrient-rich food sources, if possible, where possible, whole foods should be the first source of nutritional intake.

The recommended dairy daily intake to ensure adequate calcium is a glass of milk (250mL), a tub of yoghurt (100g) and piece of cheese (30g –the size of a domino). However there is clearly more to dairy calcium than just strong bones. The architecture of the food source also affects calcium’s functionality.

The key message: consume sufficient wholefood dairy calcium and consume variety. You’ll have all bases covered, including the pleasure of eating whole foods rather than the tastelessness of popping pills.

Banner image: Ragesoss/Wikicommons