Politics & Society

France clearly ‘On the Move’

The ‘Yellow Vest’ protestors in France are writing out books of grievances just like their forbears from the 1789 revolution in what is a critical challenge for President Macron

Published 11 December 2018

Emmanuel Macron hit the French political scene like a meteor.

He launched his political party La République en Marche! (The Republic on the Move!) in April 2016. Little over one year later, in May 2017, Macron became President of the Fifth French Republic by a percentage margin of about 65:35 over Marine Le Pen. Elected President at the age of 39, he is France’s youngest leader since Napoleon Bonaparte became Emperor aged 35 in 1804.

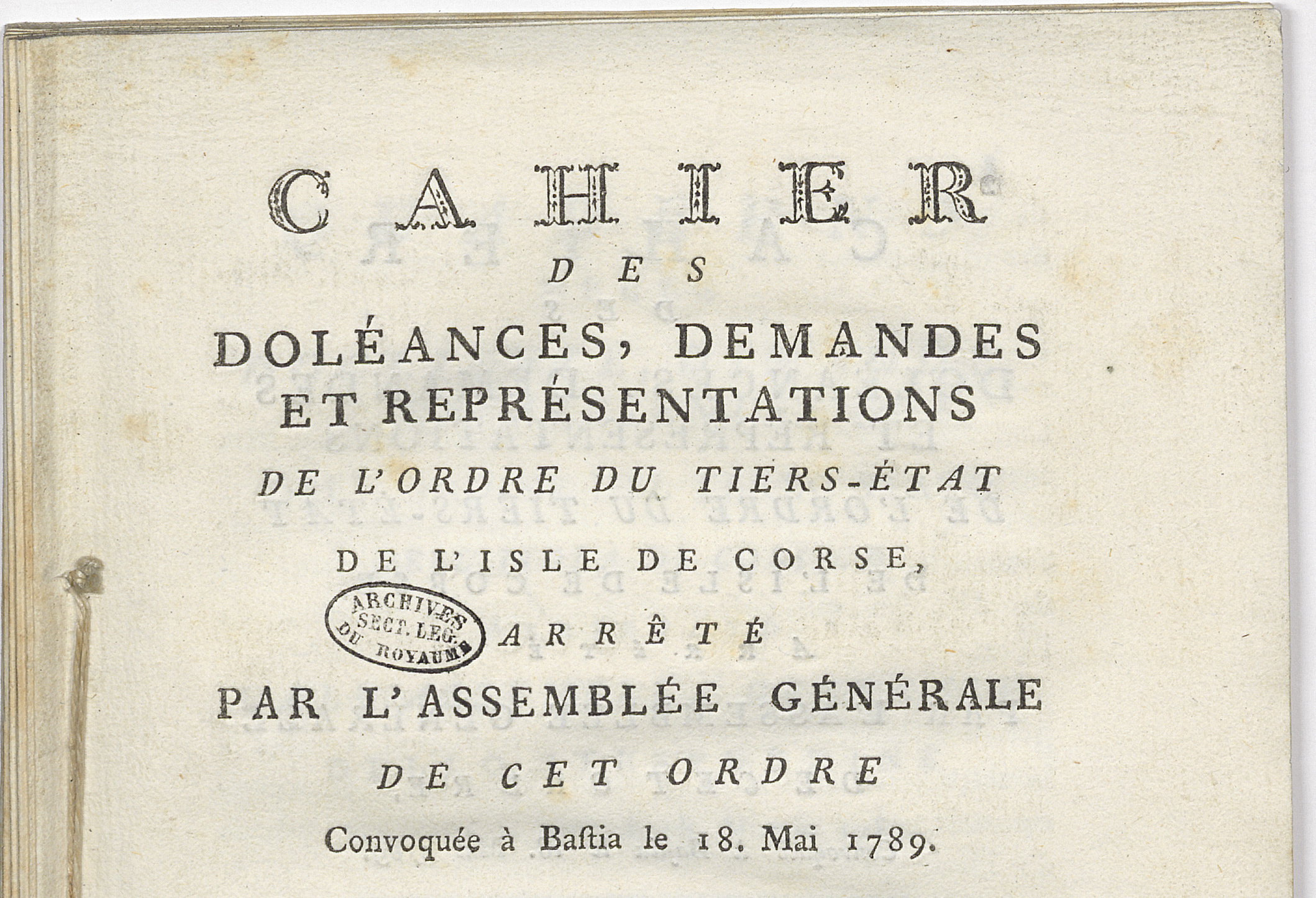

Some 18 months later history looks to be echoing again for Macron, but this time it is the tumult of the 1789 revolution. And rather than tricolour cockades, the thousands of protestors are donning that symbol of ordinary people, the yellow safety vests (gilets jaunes) that motorists must carry in case of accidents. Most eerily, the protestors are compiling cahiers de doléances (‘books of grievances’) just as the citizens of 1789 did.

What has gone so wrong so quickly for the French President?

Politics & Society

France clearly ‘On the Move’

In the June 2017 parliamentary elections that followed his presidential win, Macron’s LREM candidates won 314 of the 577 constituencies – a startling victory for a party little more than one year old. Support for the dominant centre-right and centre-left parties imploded. Astonishingly, two-thirds of all MPs were new to the National Assembly, and these are people whose election was very largely dependent on Macron’s popularity.

His voters were disproportionately highly educated, employed residents of major cities, not the disaffected and unemployed of the suburbs and country towns. His own candidates, too, were disproportionately CEOs, lawyers and doctors, university professors, and managers.

Macron insisted during his presidential campaign that he is neither right nor left, but rather a centrist liberal. He meant this in the sense of being progressive on social issues like the environment but an economic liberal on issues like labour market reform and free trade. He has argued that old divisions of ‘left’ and ‘right’ have been replaced by those between ‘progressives’ and ‘conservatives’.

Macron has faced challenges that have proved too great for any of his predecessors going back forty years, and which are similar to those confronting most of Europe:

What can be done about long-term double-digit unemployment of about 10 per cent, which rises to 25 per cent among young people?

How can very high public expenditure (57 per cent of GDP in 2015 compared with 36 per cent in Australia) be sustained when ‘general government debt’ is already very high (in 2017 some 124 per cent of GDP compared with 66 per cent in Australia)?

Politics & Society

A GFC 2.0 would remake the world in dangerous ways

His major reforms have been to loosen France’s highly protective labour laws, and to change pensions and unemployment benefits, in the hope of both reducing the massive state deficit and inducing employers to hire more employees.

But how can such reforms be secured without undermining France’s highly valued social protections? Simmering discontent among the mass of wage-earners, retirees and welfare recipients was focussed on a series on minor but deeply felt cuts to purchasing power while the well-to-do benefitted from tax cuts.

This discontent exploded on 17 November when a spike in diesel and petrol prices coincided with increased fuel taxes, all part – so Macron insisted – of the drive to reduce carbon emissions.

It was a brilliant tactic of the protestors to adopt the symbolic ‘uniform’ of the yellow safety vests, providing high visibility at no cost and highlighting the presence of suburban and provincial people dependent on their cars. There is no formal organisation or leadership of the gilets jaunes and certainly no ‘platform’. Social media has provided the wherewithal.

So, who are the Yellow Vests?

Media attention has focussed too much on the spectacular scenes of destruction in Paris by the few thousand casseurs (‘smashers’) of the extreme right and anarchist left. The great mass of protestors in Paris and the provinces – some 125,000 on Saturday 8 December – are ordinary middle and lower-middle class French people, disproportionately from the suburbs and provincial towns and cities. Among them are many retirees whose minimum pension is 8,500 euros or A$12,500 (compared with a minimum A$24,000 in Australia).

Politics & Society

Why nerd politics is here to stay

What do the Yellow Vests want?

One of the most intriguing elements of the protests is the adaptation of a public forum not used for 230 years. When Louis XVI called a meeting for May 1789 of representatives of his subjects (the Estates-General), as part of the process he instructed the people of the 40,000 parishes of his kingdom to draw up cahiers de doléances (‘books of grievances’) for representatives to bring to Versailles.

These are an unparalleled resource for historians about the grievances and demands of ordinary people on the eve of Revolution. Now many of France’s 36,000 communes have similarly opened new ‘books of grievances’, taking up an idea popularised by the sociologist Bruno Latour.

What the ‘books’ reveal are a maze of resentments, many of them contradictory – demands for lower taxes but higher social welfare benefits; cheaper diesel but more action on climate change; lower prices but higher wages; more university places but no fees. Underpinning them all, however, is a deep resentment of ‘them’ – the well-to-do of France’s ‘political class’ and its allies in the business sector and the Parisian bureaucracy, who are seen as the beneficiaries of the global economy. Macron is derided as the ‘President of the rich’, a new Louis XVI too arrogant to listen.

The consequences of the protests go well beyond France. At the heart of Macron’s presidential programme was a commitment to Europe and to continuing to work closely with Germany. He sees the Euro zone as the platform on which the French economy will be based and is committed to the Paris agreement on climate change. His international stature has been based on his reiteration of the European mission against the surge of xenophobic nationalism around the world, and his preparedness to criticise both Putin and Trump.

Now he is being openly mocked by Trump and stands to lose his moral high ground in Europe. The stakes are high.

After his election, Macron announced that he wanted to be a ‘Jupiterian’ president above the daily political fray, but now he is accused of being too aloof from mere mortals.

Politics & Society

Searching for Democracy 2.0 without losing Democracy 1.0

He risks indeed being a meteor rather than a planet. Although he is President until 2022, he faces his greatest challenge right now. On Monday 10 December he announced a series of responses to the Yellow Vests, including an increase in the annual minimum wage of 1,200 euros (A$1,800), an increase in the minimum pension and tougher measures against tax evasion, but no backtracking on earlier property tax cuts for the wealthy. Immediate reactions have suggested that the measures won’t appease the Yellow Vests even if the protests dissipate.

There are few countries in the world more difficult to govern – French people rightly pride themselves on a vigorous democratic culture fuelled by a history linked to the ‘rights of man’, revolutionary upheavals and bitter social division. Macron has also announced that he wants a public debate “without precedent”, and “region by region”, on issues including the environment, immigration and decentralisation. The ‘books of grievances’ of 2018 may be a starting point for the debates.

The ‘books of grievances’ of 1789 didn’t turn out well for Louis XVI. The sad irony – one that tells us much about the longue durée (long term currents) of history – is that the Revolution of 1789 was infused with the optimism of the ‘Enlightenment’, and the international ‘republic of letters’, while at the heart of the Yellow Vests movement is anxiety about the impact of internationalism on economic security, the standard of living and immigration.

Banner Image: Getty Images