Politics & Society

Do we really need a tracking app and can we trust it?

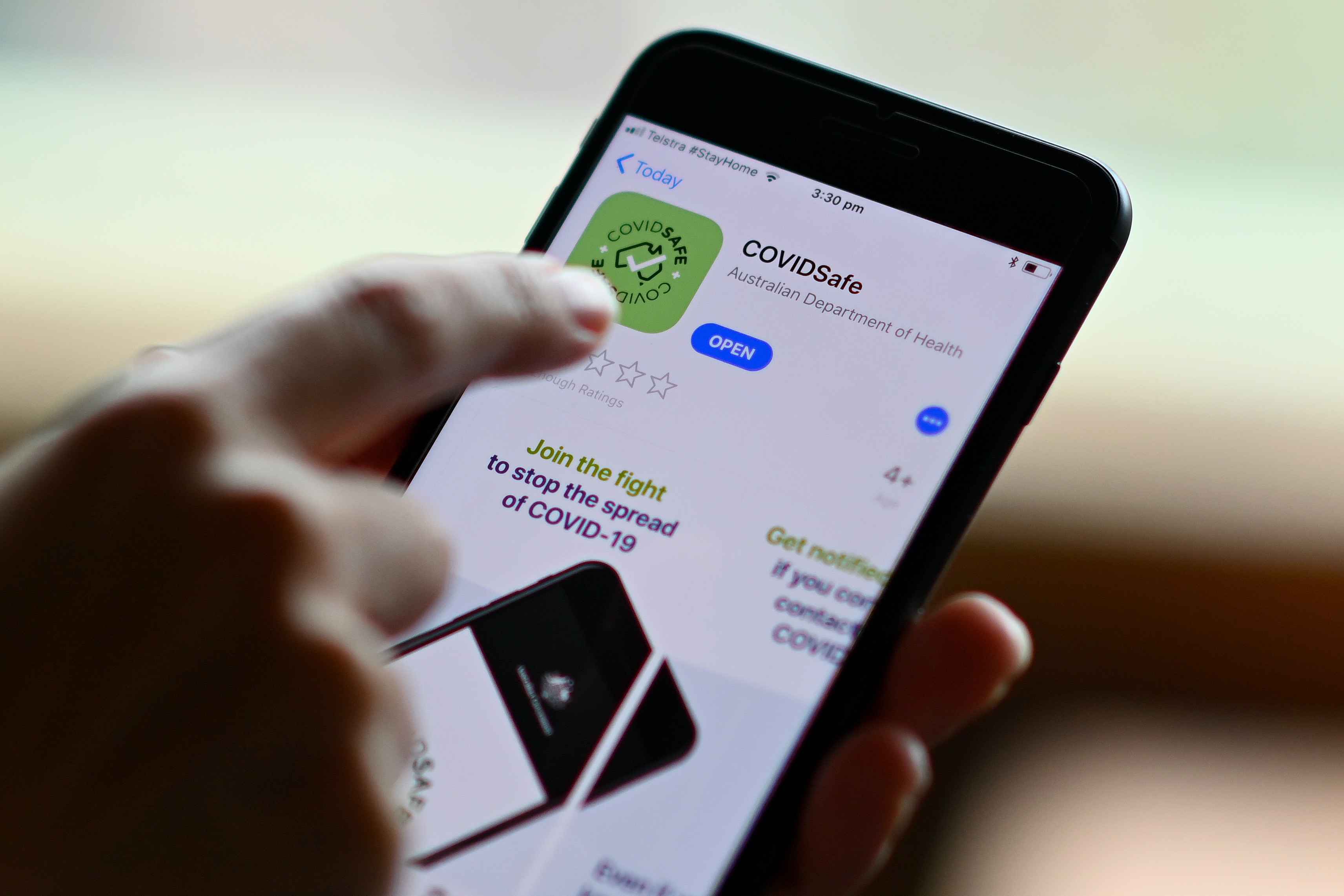

Questions remain over measuring the effectiveness of the Australian government’s tracking app, COVIDSafe, along with the mission creep it is sure to entail

Published 11 May 2020

Two weeks ago, governments in Queensland and Western Australia announced that they would start lifting some restrictions on movement and gatherings. Hours after these announcements, COVIDSafe, Australia’s new ‘contact tracing’ app, was released.

It’s hard to imagine that the timing was a coincidence.

The federal government had already signalled that the app would be one of three key pillars of Australia’s ‘exit strategy’ from shutdown.

Amid all the talk of ‘war bonds’ and ‘national service’, text message campaigns and promises that the app would help us get back to the pub, that exit strategy is now being implemented.

COVIDSafe has so far been downloaded 5.5 million times, or about halfway towards the government’s target of 40 per cent of the population.

Politics & Society

Do we really need a tracking app and can we trust it?

When the draft legislation detailing the app’s regulatory framework was finally released on 4 May, it was mostly what we’d been promised. From a privacy perspective, as things currently stand, COVIDSafe seems relatively benign (though it depends whether you’re comparing it to a mask or My Health Record).

But privacy isn’t the only concern when it comes to COVIDSafe. And there are some major assumptions and blind spots in the way the conversation has so far been conducted.

The most important of these is efficacy: the idea that the app will actually work if enough people download it. Currently, there has been far too little questioning of this basic premise.

Of course, there has been plenty of scientific modelling (much of which, by the way, suggests that even Australia’s 40 per cent target is far too low).

But TraceTogether, the Singaporean app on which COVIDSafe is directly based, was a spectacular failure.

Since its release on 20 March, and with downloads currently sitting at around 1.4 million or 25 per cent of the population, the number of coronavirus cases in Singapore has risen from 385 to nearly 22,000.

Politics & Society

The cost to freedom in the war against COVID-19

No doubt, the reasons for this 57-fold increase are complicated. But as far as the app is concerned, the issues are about more than download numbers.

Bluetooth is not a robust technology.

Even its inventors are concerned about its reliability in the context of contact tracing. And being required to keep your Bluetooth on constantly exposes you to a significantly increased security risk.

Initial problems with the app’s functionality on iPhones have already pushed the government to move towards integrating the Apple-Google collaborative API (the software intermediary that allows two applications to talk to each other).

The developers of TraceTogether are doing the same. The tech giants have so much power here that it is proving near impossible for sovereign nations to go it alone.

And of course, users still need to remember to take their phones with them, keep their Bluetooth on and not buried deep in a bag where functionality will be impaired.

According to Associate Professor Adam Dunn, Head of Biomedical Informatics and Digital Health in the School of Medical Sciences at the University of Sydney in a recent talk, even if 40 per cent of the population downloaded the app and, optimistically, half of them used it properly at all times, “the likelihood of registering a contact between any two people is four per cent”.

Sciences & Technology

Modelling the spread of COVID-19

Even in this “very optimistic” scenario, as Associate Professor Dunn puts it, fewer than one in twenty potential contacts will be captured.

At present, he says, the chance is “effectively closer to zero”. And that’s without accounting for the vagaries of Bluetooth noted above.

When Scott Morrison says easing restrictions depends on adequate uptake of COVIDSafe, it’s worth keeping these numbers and the Singaporean case in mind.

This is a population-wide experiment, make no mistake. We have very little idea whether digital contact tracing will work in Australia, or what ‘working’ would even look like.

How long will community transmission rates need to remain ‘low’, for instance, in order for COVIDSafe to be considered a success? What precise role will the app need to have played in this respect?

What if, as in Singapore, numbers start to rise again? Will this be presented to us as evidence of the app’s failure, that – far from being a magic technological bullet – it provoked a false sense of security?

Or, as seems more likely, will rising numbers be framed as reason to demand yet more data along with stricter enforcement measures?

When and according to what criteria will Greg Hunt determine that “the use of COVIDSafe is no longer required” for the purposes of the app’s enabling legislation?

Is there any plausible scenario here where COVIDSafe doesn’t help to smooth the way for further dataveillance and control by both the state and corporations in the name of public health?

The only thing we can be certain of when it comes to COVIDSafe is that it will not be a quick fix. As a result, the most important questions politically and legally speaking are still to come.

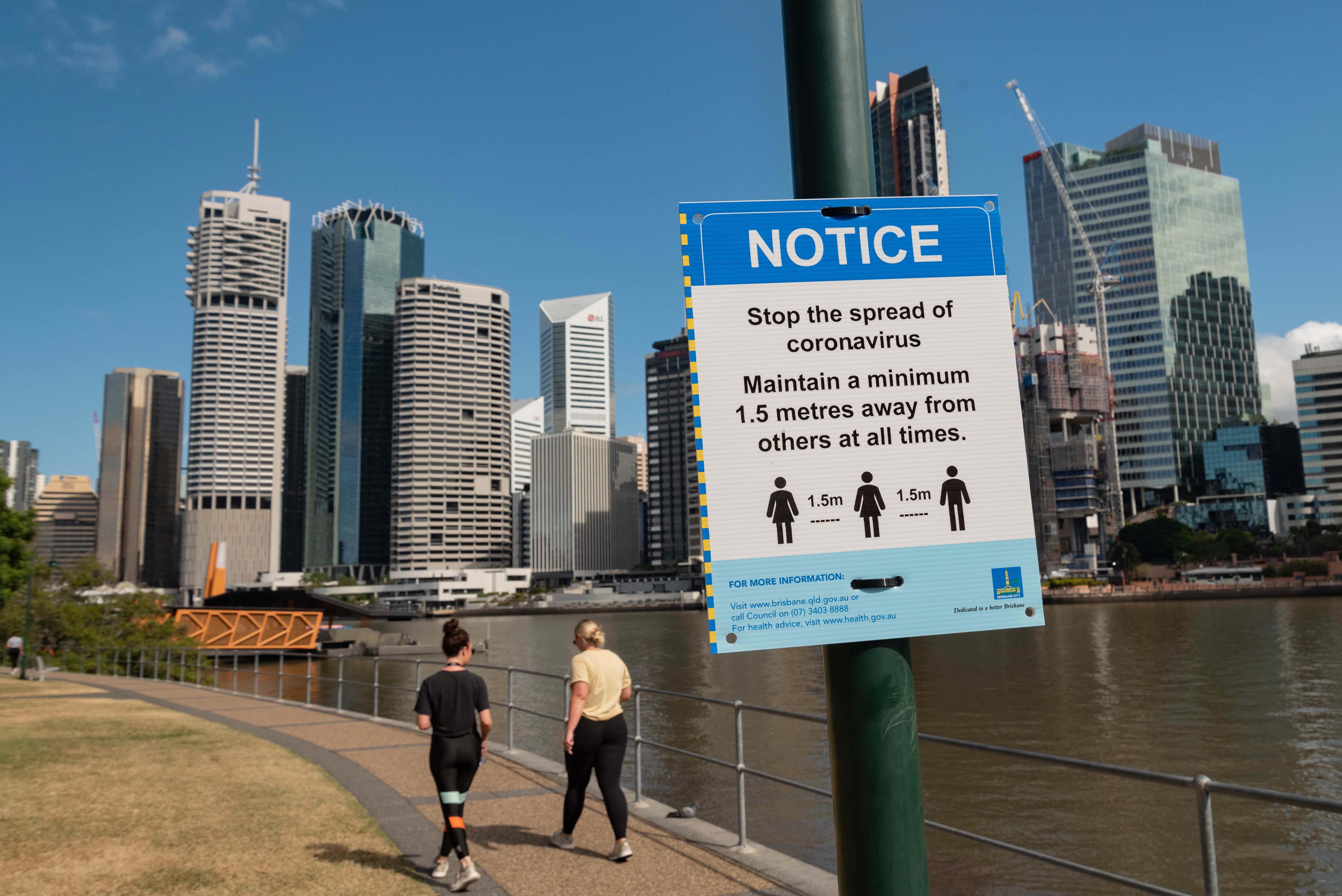

The fact that, for now, the government has been persuaded not to demand our location data, as in the UK or India, or make the app a condition of access to public or private space, as in South Korea, India and China, should be cold comfort.

As Australian journalist Bernard Keane argues in Crikey, the question isn’t so much whether COVIDSafe is a threat to your privacy, but whether the government is.

This is a government that raids journalists’ homes, that not only legislated “one of the most comprehensive and intrusive data collection schemes in the western world” with its notorious metadata retention laws but then immediately handed access to that data to the very agencies it had expressly ruled out in the first instance.

Look at the laundry list of ‘tech fails and data breaches’ published recently in the Guardian.

In this context, concerns about ‘mission creep’ are not paranoid. They are empirically justified. Indeed, Scott Morrison has already shown his hand here. He’d make COVIDSafe mandatory if he could. And he’s not the only one.

Health & Medicine

Our new research reality in the face of COVID-19

Let’s see what happens if the numbers spike again.

Even if they don’t and COVIDSafe goes more quietly than it arrived, digital contact tracing will remain part of the global conversation for a long time to come. And it is only one of many putative technological fixes that will require even more political and legal attention.

Meanwhile, the ‘machine diagnostics’ business is booming, and with scant oversight.

One Chinese startup has already sold 1000 pairs of ‘coronavirus-fighting smart glasses that can ‘see’ your temperature’ to governments, businesses and schools across the country.

A professor at the University of South Australia and the Department of Defence is currently developing a ‘pandemic drone’ designed to detect coronavirus symptoms from above.

Unsurprisingly, ‘innovative’ new surveillance technologies are coming out of the woodwork. In the US, Andrew Ng’s Landing AI has developed a ‘social distancing detector’ that would monitor employee movements in their workplace, and issue an alert when anyone is less than the desired distance from a colleague.

And Clearview AI, the notorious US company that already provides facial-recognition services to the Australian police, is currently touting facial-recognition based contact tracing to three US States.

Politics & Society

Are our new virtual workplaces equitable?

For writer, activist, and political thinker Naomi Klein, “a coherent Pandemic Shock Doctrine is beginning to emerge”.

COVIDSafe is not so much the problem, in other words, as the broader technological and political ideology of which it is a part, and will help to entrench.

The tech writer and critic Evgeny Morozov calls it ‘technological solutionism’: the growing belief, both in governments and publics across the world, that, whatever the policy alternatives, no matter the risks or likely efficacy, “there’s an app for that”. ‘To save everything, click here’ as the title of his 2013 book memorably put it.

As public services and structures of accountability are increasingly dismantled (remember, COVIDSafe has yet to be debated in Parliament), the appeal of technological solutionism only grows.

This way of thinking is much more dangerous than COVIDSafe, or indeed any individual app. It is a way of thinking we urgently need to resist.

Banner: Getty Images