‘Finding an Indigenous voice’

The second volume of the truth-telling initiative, Dhoombak Goobgoowana, shares the steps, and missteps, on the road to finding an Indigenous Voice at the University of Melbourne

Published 12 August 2025

The procession that entered Wilson Hall in September 2012 included the University of Melbourne’s two Indigenous professors, Marcia Langton and Ian Anderson.

Professor Anderson was to be conferred that day with an honorary doctorate in medical science for his skilful blending of ‘medical and sociocultural’ knowledge, and his leadership on a wide range of public and university bodies and committees, including Onemda and the Lowitja Institute.

Professor Langton was the University’s first Indigenous professor, and Anderson, wearing a possum-skin cloak for the procession, would become the University’s first Indigenous pro vice-chancellor in 2014.

A generation earlier, such a scene would have been unimaginable. Australian universities lagged well behind their peers in bringing Indigenous people into the academy.

Canada produced its first Indigenous graduate in 1791, Aotearoa New Zealand in 1903, while the first recorded Indigenous person to graduate from an Australian university was Margaret Williams-Weir, who was awarded a Diploma of Education by the University of Melbourne in 1959, more than 100 years after it opened.

The University’s second recorded Indigenous graduate, Colin Bourke, was awarded a Bachelor of Commerce degree in 1974 and then a Bachelor of Education in 1976.

The absence of graduates in Australia was a reflection of crippling social disadvantage and the meagre educational opportunities Indigenous people had beyond elementary schooling, as well as draconian laws that effectively blocked Indigenous people’s freedom to go to university.

These constraints were caused in part by education policies informed by race science, which claimed that Indigenous people had little capacity for learning.

In response to pressure from the Indigenous community, the University established the Aboriginal Liaison Office in 1975. This created a beachhead within the University, and an interface with Indigenous communities.

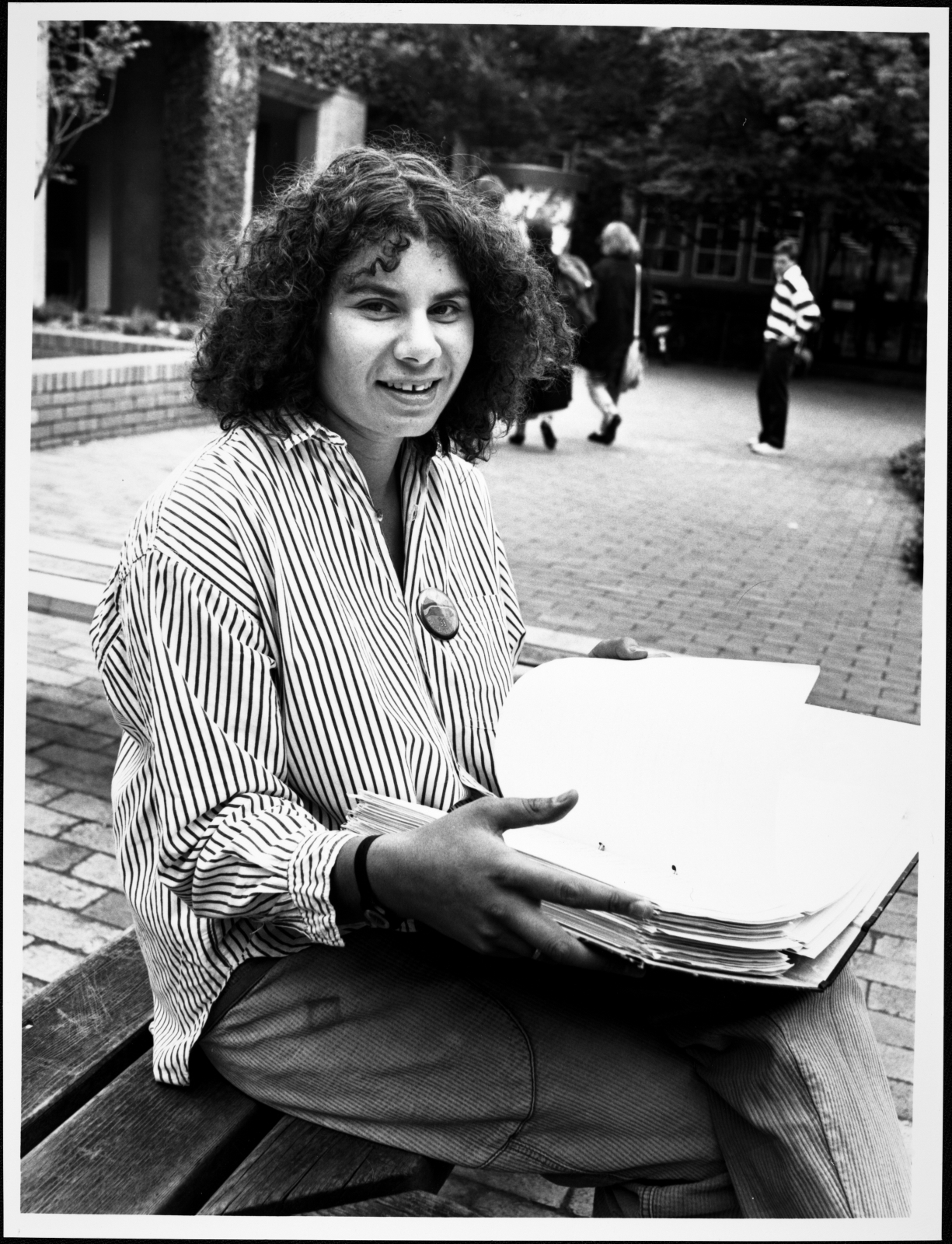

In a 1988 video, Aboriginal Liaison Officer Lisa Bellear identified shortfalls in the number of Indigenous professionals needed to tackle the social, legal and health issues faced by Indigenous communities.

There had not been, up to that point, any Indigenous students in engineering and architecture, Bellear observed. There was also a desperate need for Indigenous medical, legal and teaching professionals.

One outcome of this shift, albeit difficult and requiring much persuasion, was the creation in 1997 of the VicHealth Koori Health Research and Community Development Unit (later Onemda) by Warwick Anderson, Rhonda Galbally and Ian Anderson.

The same trend could be observed in the law, as Indigenous voices pressed for land rights, and the recognition of Indigenous tribal law, practices which have subverted longstanding and sometimes common-law assumptions, and improved Indigenous outcomes with the law.

In engineering, the acceptance of the value of triple-bottom-line planning has begun a process of accounting for traditional land uses, and greater consideration of sustainable development.

In education, there is a growing willingness not only to impose curriculum on students but also to include traditional knowledge.

This has helped to reverse the longstanding role that teachers played in stifling culture, Indigenous language and voice, remaking schooling to enhance and encourage traditional cultures.

Accompanying these shifts was the recognition of Indigenous knowledge in the University.

Marcia Langton, who arrived at the University in February 2000 as the first professor of Australian Indigenous Studies, set about establishing an Indigenous Studies program.

Under her leadership, three subjects on Yolŋu culture, Aboriginal land tenure and native title were developed, and these formed the core of a program that grew to 36 subjects in the Faculty of Arts.

This was a strong basis for what followed.

The Australian Indigenous Studies program also fostered an Indigenous research culture.

This was a high priority for Anderson and Langton, and, initially using philanthropic donations from the Pratt Foundation and others, they established the Summer School for Indigenous Postgraduate Students.

The extraordinary success of these programs is reflected in the schemes developed by the Australian Research Council, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and the Medical Research Future Fund, and the subsequent creation of the dedicated Indigenous Knowledge Institute in 2020.

Langton and Anderson were the University’s only full-time Indigenous academics in 2000. In June 2024, there were 99, including 22 professors and associate professors.

Several also hold executive leadership positions: Langton as associate provost; the first Indigenous deputy vice-chancellor, Barry Judd; and the fourth Indigenous pro vice-chancellor, Tiriki Onus.

When Barry Judd took up his initial pro vice-chancellor appointment in January 2022, the ongoing need for a university-wide strategy was clear.

He developed and socialised the 2023 Murmuk Djerring strategy that guides the University’s engagement with Indigenous Australians at the highest policy level and is applicable to all faculties, institutes and centres.

Partnerships with communities were recognised as a key part of how Indigenous studies research and engagement are conducted – with, not about, Indigenous people.

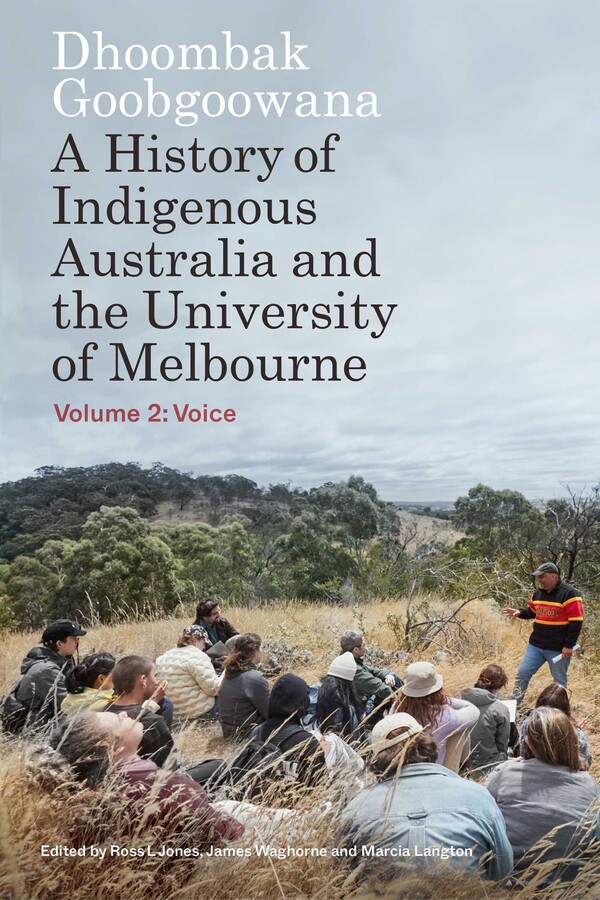

Dhoombak Goobgoowana Volume 2: Voice is the second volume in the University’s attempt to address the complexity if its connection with Indigenous Australia.

It has been overseen by an Indigenous steering committee and includes many Indigenous authors, although the non-Indigenous contributors have demonstrated that they bear a greater and more substantial responsibility for truth-telling and reconciliation.

The book explores the profound influence of the arrival of the Indigenous voice. It shows where idealism has fallen short, and where stated objectives have not been reflected in the level of institutional support.

It is a story punctuated with moments of success, such as the arrival of the new Indigenous leadership, Margaret Williams-Weir’s watershed graduation, and medical initiatives that have produced measurable improvements in combating the pernicious effects of white colonisation.

It is salient to recall that life expectancy for Indigenous Australians in 1788 was often superior to the white sailors who arrived on the First Fleet.

Most of all, it shows the hard work of Indigenous people in confronting an institution at times hostile to their presence and at others indifferent, and on whom great expectations are loaded, and who are asked to do so much.

This is an edited extract from Dhoombak Goobgoowana – A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne – Part 2: Voice, published by Melbourne University Publishing and edited by Dr Ross Jones, Dr James Waghorne and Professor Marcia Langton. Hard copies are available to purchase, and a free digital copy is available through an open-access portal.