Five things we learned from the Biden Climate Summit

US President Joe Biden called on 40 world leaders to cut emissions during his Climate Summit - but what did we learn from the first virtual climate meeting of its kind?

Published 26 April 2021

President Biden’s Climate Summit, held to coincide with Earth Day, shone the international spotlight on the issue of climate change.

The Summit was a crucial step in galvanising world leaders to increase the ambition of their national greenhouse gas emissions targets ahead of the United Nations Conference, COP26, which will be held in Glasgow in November.

As UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, reminded countries at the conclusion of the Biden Summit, this is a “make-or-break year for people and planet.”

But what have we learned from the two-day Summit, the first virtual climate meeting of its kind? Is the tide for climate action turning? And will countries emerge from the COVID crisis with a plan to address climate change with the urgency climate science says is needed?

Here are my five key takeaways.

1. the united states is back, big time

The clearest message to emerge from the Biden Summit is that the United States is “unreservedly back” on the international climate stage after four years in the wilderness under President Trump.

And it also clearly demonstrated the US wants to play a leadership role.

Not only has it rejoined the Paris Agreement, but the Biden administration is also showing it’s prepared to “walk the talk” on climate action.

At the summit, President Biden committed the US to cutting its emissions in half by 2030. The US is also ramping up pressure on other countries to do more.

Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken, warned before the Summit: “When countries continue to rely on coal for a significant amount of their energy, or invest in new coal factories, or allow for massive deforestation, they will hear from the United States and our partners about how harmful these actions are.”

2. us leadership can be effective in spurring on its allies

Other developed countries largely followed the United States’ lead at the summit, deepening their near-term emissions reduction commitments.

The UK promised a 78 per cent cut from 1990 levels by 2035, Japan is aiming for a 46 per cent cut by 2030 and Canada has put forward a cut of 40-45 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030.

The European Union is also stepping up its climate action, pledging to reduce emissions by 55 per cent below 1990 levels by 2030.

Environment

The investor-led push on climate change

Like the US, these countries and the EU all also have pledges to reach “net zero” emissions by 2050.

This action may have happened without the Biden Summit, and question marks remain over whether all these pledges will translate into on-the-ground action, but overall there was palpable relief among Western leaders and new confidence that – as Italian Prime Minister,Mario Draghi, put it – “together we will win this challenge”.

3. but australia was conspicuous for its silence

Amongst a clamour for ambitious action, Prime Minister Scott Morrison was literally inaudible – his microphone muted – for the first few moments of his Summit speech.

As one DC climate policy wonk quipped, it was “a perfect metaphor” for Australia’s contribution to the global climate debate.

The Summit showed that even considerable international pressure is not sufficient to overcome domestic climate political factors in Australia, at least for the moment. Scott Morrison stuck doggedly to the Abbott-era 2030 emissions pledge, insisting that it is outcomes not targets that matter.

Close watchers of Australian climate politics, though, have pointed out subtle changes occurring in the Coalition government’s rhetoric around climate (from job-destroying to job-creating, at least in the regions) and incremental movements towards a net-zero-by-2050 target.

But we are not likely to hear a definitive statement on that until just before the Glasgow meeting in November.

While these shifts might be ground-breaking in a domestic political context, they seem very timid from a global perspective. After this performance, Australia will need to work very hard to shake the climate laggard tag before November.

4. the continuing decline of global support for coal

This has important implications for Australia as the world’s largest exporter of metallurgical coal (used for steel production) and its second largest exporter of thermal coal (used for energy production).

But now some of our largest customers in Asia, like China, Japan and Korea, are moving away from coal.

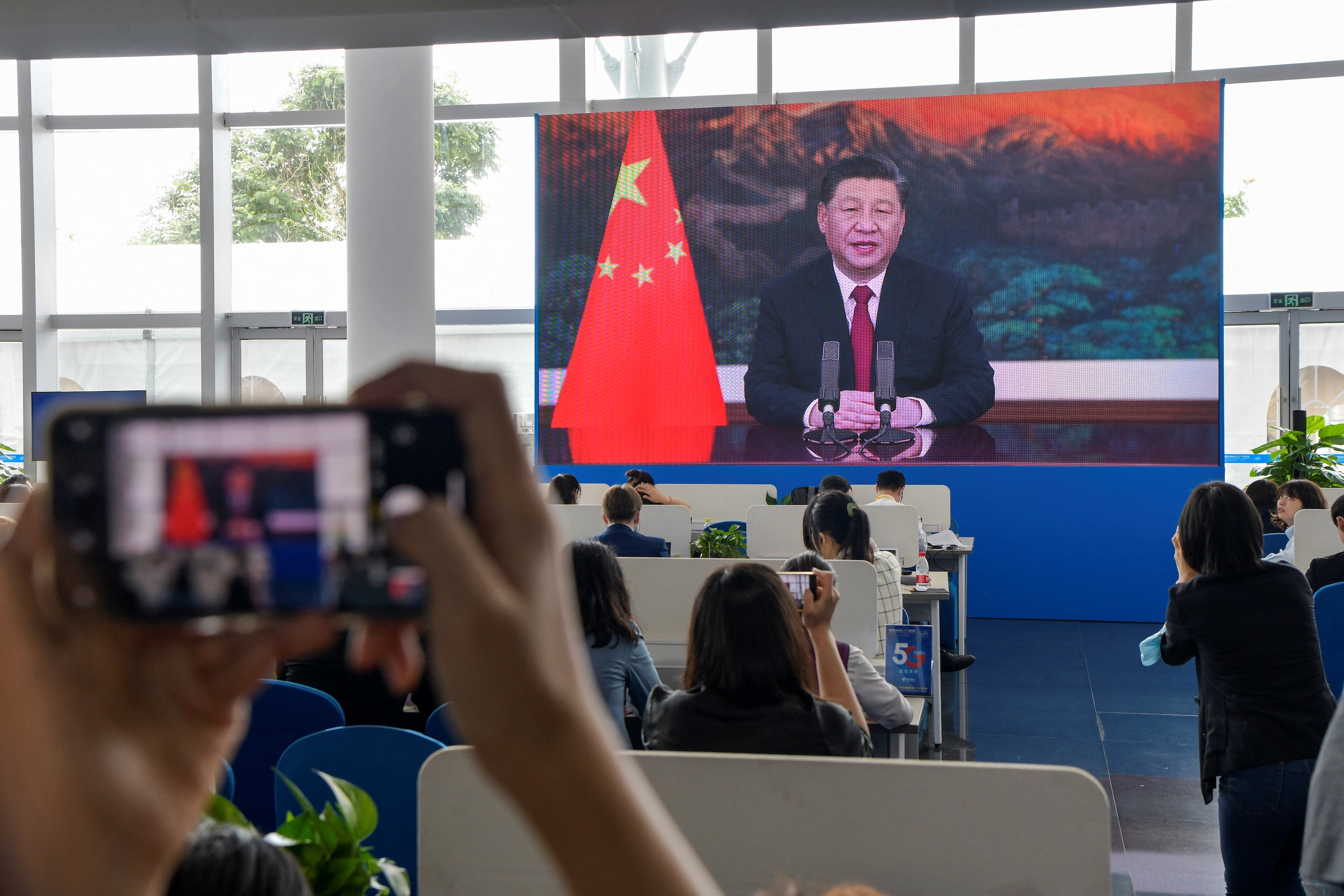

The most important announcement on this at the Summit came from China’s President Xi Jinping ,who pledged China would “strictly limit increasing coal consumption” in the next five years and phase it down in the following five years.

Investment in coal from China, Japan and Korea was also in the crosshairs of the US heading into the Summit.

In a sign that this pressure had borne fruit, South Korea’s President, Moon Jae, pledged at the Summit that Korea will end public financing of coal-fired power plants overseas.

The Korean announcement reflects a broader move away from private and public financing of coal-fired power that should sound the death knell for plans for further coal power stations in Australia, no matter how much they may be spruiked by some Coalition politicians.

Sciences & Technology

The costs and benefits of a clean economy

5. nothing beats a face-to-face meeting

This was a well-produced, carefully staged virtual event which achieved its goal of building momentum for global climate action, despite some technical glitches.

But the images of world leaders sitting in front of TV screens, mainly delivering speeches from teleprompter, only served to underline the differences between this event and the usual hustle-and-bustle of an in-person conference where there are opportunities for leaders to talk, share ideas, exert informal pressure, build coalitions and drive momentum.

The countries most vulnerable to climate change, such as the tiny Marshall Islands, had some speaking slots at the Summit, but overall had limited opportunities to make the moral case for action.

In the world of climate talks it seems that like much else in our COVID-affected world, nothing beats face-to-face.

Banner: AAP