Arts & Culture

Welcome to the club? Women in football

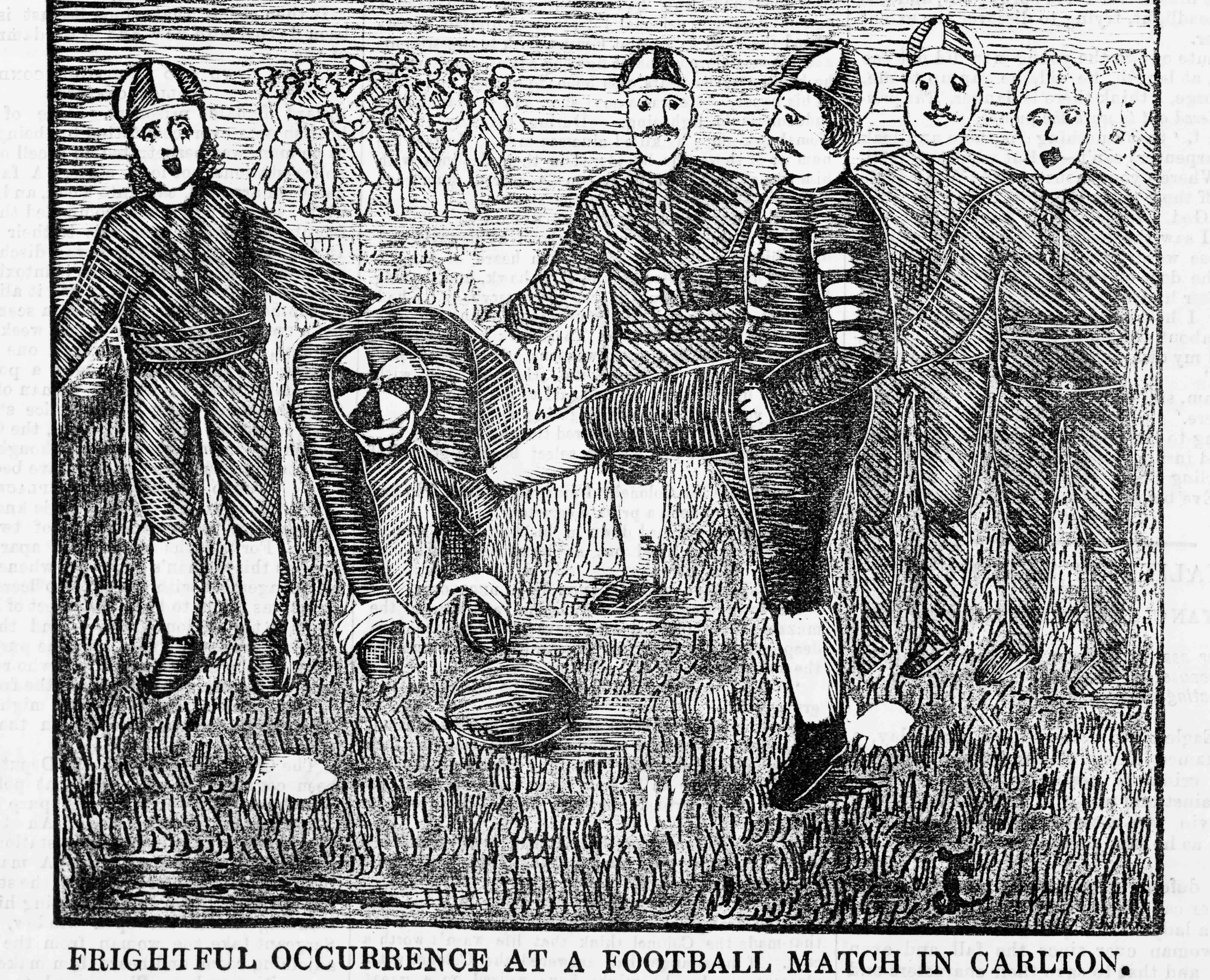

Aussie Rules has the power to bring people together, but throughout history, it has also reflected the struggle for social change

Published 2 May 2018

Footy holds a central place in the cultural life of many Australians today. Over the last one hundred years or so, Australian Rules has become “more deeply entangled with notions of what it meant to be Australian”.

By understanding footy – past and present – we can get a snapshot of Australian cultural history. And not just our sporting history – but societal changes, particularly where gender and race play a central role.

Women have been playing organised Australian Rules football since 1915, and at the time, it mostly revolved around workplaces. There’s also a history of women being considered acceptable in this space – as spectators. For example, some women watching in 1896 were described as “sitting stoically in the rain, decorating their prams in club colours, yelling abuse at the umpire, and, quite often, leaning over the boundary line to jab him with a hairpin or strike him with an umbrella”.

In 1921, the school principals of Melbourne’s Church of England Girls’ Grammar School (Merton Hall) and Methodist Ladies College (MLC) were opposed to women playing football. The Merton Hall principal “strongly [disapproved] of women playing any game that is likely to bring them into the public eye”, while the MLC principal declared that “grace rather than muscular strength is the Australian woman’s characteristic”. Additionally, “a leading lady doctor of Collins street’ said at the time: “Hockey is strenuous enough, and it would be a great mistake for girls to begin football”.

Arts & Culture

Welcome to the club? Women in football

But there has always been skepticism expressed about women’s abilities to properly act on the footy field. In 1933, the Sporting Globe noted that: “Many attempts have been made in the past to encourage the weaker sex to play football, but public opinion, coupled with the general feeling of most sports girls, has forced the movements to be abandoned.”

And some of these concerns about what women can do with their bodies in public sporting areas continue to exist in the 21st century. Current, seemingly paternalistic, plans to change the rules for the AFLW competition diminish the contact and physical nature of the game – failing to see that “[football] is a socially-sanctioned environment for women to be as aggressive and brutish as they like… It’s not an opportunity society often provides”.

Physicality and aggression have shaped the history of footy in this country.

In 1881, the Bendigo Advertiser reported, in a column headlined Football, or Riotous Brutality, on a match between the Bendigo and Sandhurst clubs in which the players were “utterly deficient of such necessary attributes to those who would like to be called young ‘men’”.

There were threats of broken bones and assaults on opposition players. Things got so bad that the paper exclaimed that “if matches between the Bendigo and Sandhurst clubs are to be attended by such riotous behaviour as was witnessed yesterday, it would be far better if the two teams never met at all”.

And this kind of violent behaviour was not limited to the players. According to the report “not only did they yell and hoot, and curse, utterly regardless of those within hearing, but they showed an inclination, in their mad excitement, to assault those players for whom they entertained a dislike”.

Politics & Society

In a league of their own

But this violence has also had a sinister side. Especially when it came to race.

Racist violence against Aboriginal players has been a constant, and particularly visible since the 1990s.

This year marked the 25th anniversary of St Kilda player Nicky Winmar’s famous declaration that he was ‘black and proud to be black’. Having played one of the best games of his career, alongside fellow St Kilda Aboriginal player Gilbert McAdam (the two of them got the 3 and 2 in the Brownlow votes that day), at the end of the game Winmar lifted his jumper and pointed to his skin – creating one of our game’s most iconic images.

Both men had been subjected to racist abuse throughout game – McAdam’s father, Charlie, a member of the Stolen Generations, had to leave the ground “in tears”, unable to listen to the abuse his son was receiving. In the aftermath, when the two men made clear they were “not going to put up with this crap” - they faced death threats and their careers were forever affected.

Many people believe that the game itself – as well as the country captivated by it – was irreversibly changed as a result of this match. It kickstarted a modern movement by Aboriginal footballers which continues to this day – fighting the racism of spectators, players, and officials within the AFL.

But this movement has its roots further back in history.

The first Aboriginal player to play VFL/AFL was Joe Johnson, an oft-forgotten half-back flanker. Described as “a very fine player”, Johnson played for Fitzroy from 1904 to 1906, including in the 1904 and 1905 premiership sides, before playing for Brunswick and Northcote.

Some histories of racism in football have been addressed. In 2016 Carlton formally acknowledged the club’s mistreatment of Sir Doug Nicholls by holding a Sir Doug Nicholls Acknowledgment. It formally recognised Nicholls’ exclusion from the team in 1927 because he was Aboriginal. Dermott Brereton has apologised for his, and Hawthorn’s, racial abuse of West Coast Eagles player Chris Lewis in the 1991 Grand Final.

Arts & Culture

Footy isn’t life or death - it’s more important

Lewis, who had been suspended for 23 games in his career, commented that “after getting suspended and not being able to play because of retaliating and all that sort of stuff, you just sort of learn to put up with it”.

There is no clear trajectory of social and sporting progress when considering the place of football in Australian society. In recent times we need only consider the increased public booing of Adam Goodes after he performed a war cry dance (created by an Aboriginal development and leadership team, The Flying Boomerangs), and his continued estrangement from the AFL community.

Or more recently, Katie Brennan’s suspension for “rough conduct” and the AFL’s transphobic decision to not allow transgender player Hannah Mouncey to nominate for the AFLW draft.

But, “football stories provide us with a starting point for other conversations”. These “other conversations” are vital.

This is part of the power of football, the potential that stories of those histories can hold for supporters and for Australian society at large.

A version of this article also appears on Dr Silverstein and Dr Tomsic’s football blog, History from the Centre Square.

Banner image: Picture ca. 1914-1916/ State Library of Victoria