Business & Economics

Thinking about using donated eggs to start a family?

Women can freeze their eggs while delaying childbirth, but many will be wasted while other women are desperate for eggs. We need a system of egg donation

Published 10 January 2021

Freezing a woman’s eggs for later use for in vitro fertilisation (IVF) was initially reserved for women with medical conditions, like cancer, which risked leaving them infertile.

But ‘elective egg freezing’ is now emerging as a relatively new option for women who want to delay childbirth while preserving their eggs for later – IVF with eggs frozen at a younger age is much more likely to be successful than IVF using fresh but older eggs.

The problem is many of these frozen eggs will simply be wasted.

Current estimates, based on limited data and demographic indicators, suggest that fewer than 20 per cent of women will return to use their eggs in the future. This is probably related to a multitude of factors including successful natural conception, remaining un-partnered or not wishing to use donor sperm.

Business & Economics

Thinking about using donated eggs to start a family?

As a result, many eggs will never be used and will eventually be discarded, providing benefit to no one.

The other problem is that it’s older women who are more likely to be able to afford the procedure of egg freezing and more likely to need the eggs in the future; but once in her late 30s or early 40s a woman’s eggs will already be past their prime, reducing the chances of successful IVF.

At the age of 45, a woman’s chance of conceiving naturally or with IVF is less than one per cent per cycle.

A younger woman is expected to be less likely to freeze her eggs because it’s likely be a bigger a financial burden, and they are less likely to utilise the eggs anyway, as their chances of starting a family naturally are still high.

Our research argues that what we need is a system in which un-used frozen eggs can be donated to women who a need them, while the cost of having the eggs frozen and stored is eventually transferred to the woman who actually uses the eggs, not the donor.

Delaying childbirth is a well-established social trend in Australia, reflecting changing social attitudes including the aspirations of women to pursue their education and careers. In the 30 years to 2017, the fertility rate of women aged 35-39 doubled, while among 40-44 year-olds – it tripled.

Health & Medicine

Predicting cancer risk from mammograms could revolutionise screening

It is estimated that about six to eight per cent of Australian women will choose not to have children. But based on current socio-demographic trends, we can expect that more and more women will either experience involuntary childlessness or not achieve their desired family size.

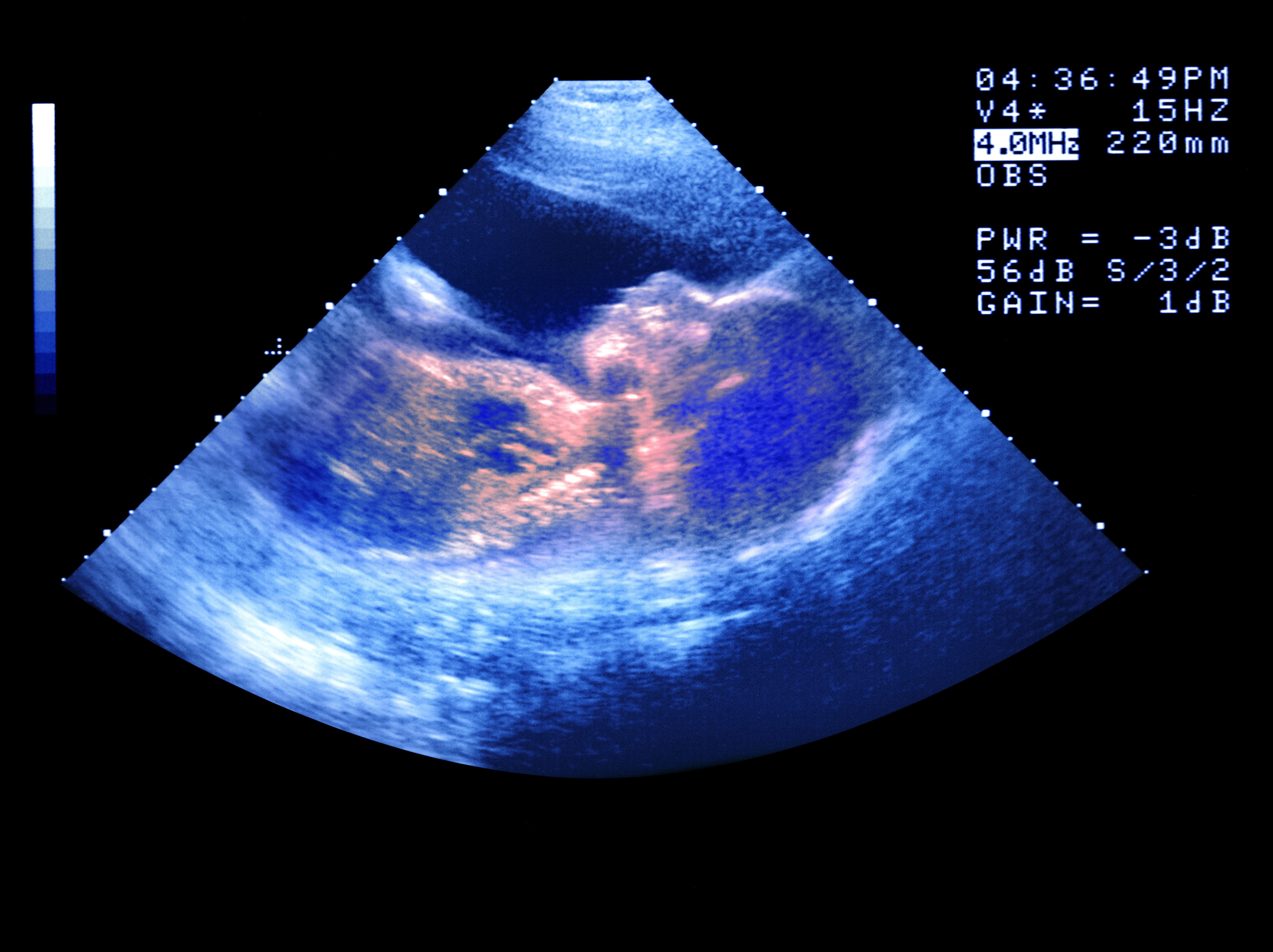

This is why cryopreservation (freezing) of mature oocytes is increasingly promoted and utilised by women to improve their chances of conceiving when they are ready. These eggs can be fertilised with the sperm of a woman’s partner or a sperm donor.

There are obvious benefits to using this technique, including greater reproductive freedom and autonomy, reducing the burden of infertility and the number of IVF cycles needed to achieve a live birth, compared to an older woman using fresh eggs.

However, unfavourable aspects of this practice include the cost and consequent inequality of access, social aspects and the waste of un-used eggs.

The trend toward delayed childbearing is also driving a rising demand for donor eggs. For those women who have not frozen their eggs at a younger age, the use of donor eggs is one of only a few viable pathways to parenthood.

Health & Medicine

Do new doctors get enough child health experience?

In much of the world only altruistic donation of biological material, including oocytes, is permitted – donors can’t sell their eggs. In Australia, the concept of altruism as the paramount principle guiding oocyte donations is enshrined in a federal statute.

This has the effect of severely restricting the availability of donor eggs, since very few women are willing to undergo an egg collection IVF cycle with no financial reward in order to donate their eggs to strangers.

For this reason, the demand for donor eggs far outweighs the supply from donors such as close friends or family members.

As a result, many Australian women are travelling overseas to countries with less stringent rules and regulations, where oocytes can be obtained from young donors in exchange for monetary inducements.

This ‘reproductive tourism’ has significant ethical, financial and medico-legal issues. Neither the donors, or recipients are protected from exploitation and fraud.

Moreover, in the past year, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, this avenue of obtaining donor oocytes has been severely restricted.

Few would disagree that wider availability of donor eggs in Australia is a desirable goal that would greatly benefit many women and couples. We are in a situation where oocytes are being stored for social reasons but many are unlikely to be used, while there is increasing demand for donor oocytes that isn’t being met.

Health & Medicine

Support after miscarriage – how can we do better?

One way to solve this problem to the benefit all parties and society at large, is to encourage women who electively freeze their eggs but then no longer require them to donate them to women who do need them.

Furthermore, compensation for donors, in the form of reimbursement of the expenses incurred in producing and storing oocytes, should be made available and paid by recipients.

This arrangement is still consistent with altruistic donation principles, since no financial inducement is offered, only the expenses incurred are reimbursed.

This is ethically acceptable, legally permissible and is consistent with the current practice of egg donation in Australia.

It would allow wider access to social egg freezing, increase the utilisation and cost-effectiveness of oocyte storage and, most importantly, significantly increase the availability of donor oocytes to those would-be mothers in need.

Disclosure: Dr Polyakov and Dr Rozen are IVF clinicians in private practice.

Banner: Tube of eggs in cryogenic (frozen) storage. Picture: Getty Images