Health & Medicine

Tailored treatment turns up heat on melanomas

From state of the art mole-mapping to new drug treatments, the way we diagnose and treat skin cancers is being revolutionised, but being sensible in the sun is still the best medicine

Published 4 January 2019

Summer time in Australia means holidays, barbecues, trips to the beach and keeping a wary eye for bush fires. It also means skin cancer.

“We always diagnose more skin cancers during summer,” says Professor Rodney Sinclair, head of dermatology at the University of Melbourne and principal of Sinclair Dermatology.

“Ultra violet light can suppress the immune system’s surveillance of rogue cells, so that instead of being killed off they survive to form a cancer. And that happens more often in summer when we are more exposed to the sun.”

Two thirds of Australians will be diagnosed with skin cancer by the time they are a 70.

The main culprit is sun exposure and sunburn.

Fortunately, most skin cancers won’t be life threatening. The least common, but most dangerous class of skin cancer is melanoma.

Melanomas account for approximately one per cent of all skin cancer in Australia, but according the Cancer Council of Australia, melanoma is the fourth most common cancer in Australia.

Health & Medicine

Tailored treatment turns up heat on melanomas

In Australia, by age 85 the chances of being diagnosed with melanoma is one-in-22 for women and one-in-13 for men.

But the good news is that new technologies and drug discoveries are radically improving our ability to diagnose and treat the disease.

The single most critical factor for improving your chances of surviving skin cancer is early detection.

Successful detection relies on both the patient keeping an educated eye on their skin, and the physician interpreting correctly what they see.

It isn’t always easy and melanomas can be missed.

But Professor Sinclair says new imaging technology is set to revolutionise how we detect skin cancers.

Professor Sinclair is referring whole-of-body imaging, like the Vectra WB360 mole and lesion mapping system, developed by technology company Canfield Scientific.

With 92 cameras, the machine can instantly take a high-resolution 3D image of someone’s entire body as they stand between its two camera-bearing arches.

In just five minutes a computer can compile the images into a single 3D picture where every blemish on the skin can be seen, zeroed-in on and assessed.

“There are four traits we look for when identifying lesions and moles that may be potential cancers – asymmetrical outline, ragged borders, the colour, and marks over six millimetres in diameter,” says Professor Sinclair.

“This technology allows us to rapidly sort, on screen, every mole and lesion on a patient.”

Health & Medicine

Why you should go on a clinical trial

He says the technology makes diagnosis quicker and more accurate.

It also provides a base line image that physicians, and patients, can use to monitor any changes in the appearance of a mole or lesion – another key sign of a potential melanoma.

At this stage there are only three Vectra WB360 machines operating in the world, two in Australia – in Melbourne (at Professor Sinclair’s clinic) and Brisbane – and one in New York. But Professor Sinclair believes it won’t be long before machines like this become standard practice.

“We could get to the point where everyone at some stage gets imaged and assessed. Everyone would then have a completely accurate image of themselves that they can use to monitor changes on their skin and share with their practitioners.”

One of the obvious applications for this imaging technology he says is in telemedicine.

“People living in country areas are more likely to die from skin cancer, and that is because of the more limited access they have to regular checks,” says Professor Sinclair.

But with the new imaging technology, Professor Sinclair says everyone in country communities could be imaged by travelling machine. and that base line information could then be easily shared and assessed electronically by a doctor anywhere when the image is updated.

“It means we could seriously improve access to services for people in country areas.”

Health & Medicine

The cells giving our immune system more punch

Advances in imaging are also creating opportunities to use virtual reality technology to enhance diagnosis and facilitate teaching.

Professor Sinclair is in a research collaboration with Deakin University to develop a virtual reality system that would allow physicians examining a patient to wear glasses that overlay the patient’s 3D image.

“A doctor could be looking at a patient and with these class be able to instantly compare what they are seeing with the earlier imaging.”

But once you have melanoma, what then?

Until recently, cancer treatments have been reliant on trying to destroy or control cancers using chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

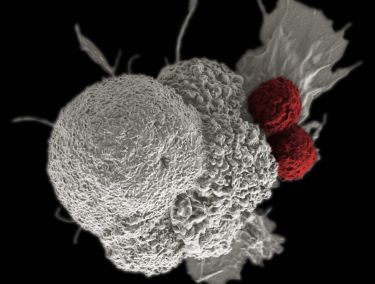

But, over the last decade, a new class of immunotherapy drugs have emerged that he says are radically improving a patient’s chances.

Immunotherapies help our immune systems to attack cancers, and the most exciting new class of these drugs are ‘Immune Check Point’ inhibitors, the first of which only came onto the market in 2011.

It was a combination of Immune Check Point inhibitors – used as part of a clinical trial – that in 2016 helped Australian Football League player Jarryd Roughead beat a melanoma that had spread internally.

He is now back playing.

Health & Medicine

Goosebumps can give us more than the shivers

Just four years earlier, says Professor Sinclair, Roughead could have been facing the same fate as former AFL great Jim Stynes who succumbed to melanoma in 2012.

“That sort of change in the space of just a few years is nothing short of miraculous,” says Professor Sinclair.

But because cancer cells are constantly adapting, check point inhibitors don’t necessarily entirely wipe out a cancer.

“To an extent each drug might be buying a patient three to five more years, by which time people will be hoping there will be a new drug around to beat a cancer that might return,” he says.

However, in the long-term Professor Sinclair says that if a broad range of check point inhibitors could be developed and used in combination, then we would have a real prospect of permanently killing off cancers.

“If we can hit cancers from enough different angles then we will be able to knock off the outliers that are getting missed.”

But while technology and research is improving our ability to diagnose and treat skin cancer, nothing beats not getting skin cancer in the first place.

And that just means being sensible in the sun.

“Education campaigns like SunSmart campaign have made a huge difference in reducing the risk of skin cancers,” says Professor Sinclair.

Sciences & Technology

Are redheads with blue eyes really going extinct?

Research published in the Medical Journal of Australia this year shows that the incidence of melanoma in Victorians aged under 55 is falling, and there are estimates the Sunsmart program prevented 43,000 skin cancers between 1988 and 2010.

So, this summer, remember to: slip on a shirt, slop on sunscreen, slap on a hat, seek shade and slide on some wraparound sunglasses.

Editor’s note: Professor Sinclair has no financial interest in the company that developed the technology. He is also a principal of Sinclair Dermatology.