Sciences & Technology

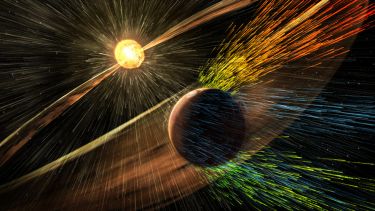

What happened to Mars’ atmosphere?

As NASA announces its aim to have humans on Mars by the 2030s via a Deep Space Gateway - humans who make the long space journey will experience health risks we’ve never faced before

Published 5 October 2017

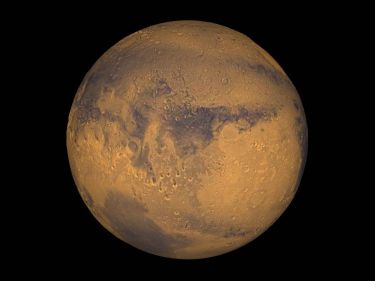

Space may be the final frontier, but if the headlines coming out of NASA are to be believed it won’t be too long before humans are boldly going where no-one has gone before - Mars.

But long-distance space travel brings with it a unique set of health problems.

How will those who make the trip cope with the mental and physical rigours of the journey? What role will isolation and stress play? And what are the health dangers?

Self-described “space nerd”, University of Melbourne training psychiatrist Dr Marc Jurblum is a medical doctor. But he’s also a member of the Australasian Society of Aerospace Medicine’s Space Life Sciences Committee. Its job is to support space medicine research and education outreach across Australia, and the Bioastronautics Australia Network.

Dr Jurblum thinks an odyssey to Mars is only a matter of time.

“I’d be very surprised if we didn’t see a Mars mission in our lifetime. We have the basic capabilities. It’s physically possible. We have the understanding and the technology to do most of it.”

Sciences & Technology

What happened to Mars’ atmosphere?

So, what are the key health issues facing prospective space travellers?

On Earth, tiny gyroscopes in your brain give you spatial awareness - they tell you when you tilt your head, accelerate, or change position.

But it’s different in space.

“In Zero G, those don’t work as well and, as a result, astronauts suffer a lot of nausea. A lot of them spend days feeling incredibly unwell. It’s like being sea sick.”

And there are many examples. In 1968, NASA launched its second human spaceflight - the Apollo 8. Astronaut Frank Borman suffered such a bad bout of space sickness on the way to the moon that Mission Control considered shortening the mission.

Fortunately, just like people going to sea eventually get their sea legs, astronauts develop space legs within about two weeks. But once they return to Earth, the opposite is true – many of them have to work hard to get their ‘Earth legs’ back.

Space travel is still inherently dangerous. Essentially you are floating through an airless vacuum in a sealed-up container, only staying alive because of the machinery recycling your air and water. There is little room to move and yoou are in constant danger from radiation and micro-meteorites.

“Any person can break given enough stress. We’re looking at how to prevent this.”

Dr Jurblum, who has a Graduate Certificate in Space Studies from the International Space University, has been involved with research groups looking at how to maintain mental health in extreme environments. Suggestions include using interventions such as meditation and the positive impact pictures of nature can have on space travellers.

“You don’t need to do anything, just having those pictures in your environment has a positive psychological effect on concentration, emotional resilience and cognitive performance,” he says.

“We don’t know what months and months of living in an unchanging capsule habitat with only blackness outside the little window will do to people’s minds,” he says.

“Even if you turn the ship around, Earth will be a distant speck of light. There’s little more than hydrogen atoms for hundreds of thousands of kilometres around you.”

Sciences & Technology

Running water = possibly life on Mars

Virtual Reality may also help by giving the astronauts a rest from the monotony.

Then there’s the issue of emotions. On Earth, if people get upset with their boss or workmate they might take out their frustrations at home or the gym. In space, astronauts can’t afford to get angry with each other - as they must be able to react really quickly, communicate and work as a team.

Dr Jurblum says astronauts often divert that anger onto Mission Control. In fact, one crew aboard the Skylab space station got so angry at mission control that the astronauts shut down communications for 24 hours.

In contrast, a positive psychological phenomenon of space travel is the “overview effect”.

“Most astronauts who have gone into space have come back with a change of perspective. They become more environmentalist, spiritual or religious.”

NASA astronaut Ron Garan described it as “the realisation that we are all travelling together on the planet and that if we all looked at the world from that perspective we would see that nothing is impossible”.

There is no gravity on the International Space Station, and Mars only has about a third of Earth’s gravity. This instantly plays havoc with the human body.

Astronaut’s faces grow puffy and round, and they constantly feel like they have the flu with blocked sinuses.

“Your body has developed to push fluid up to your brain against gravity. In space, too much fluid gets pushed up to the top half of your body so it then tries to get rid of fluid by making you urinate more, and you end up dehydrated,” says Dr Jurblum.

He also says our muscles are so used to fighting gravity on Earth that its absence means they weaken and waste.

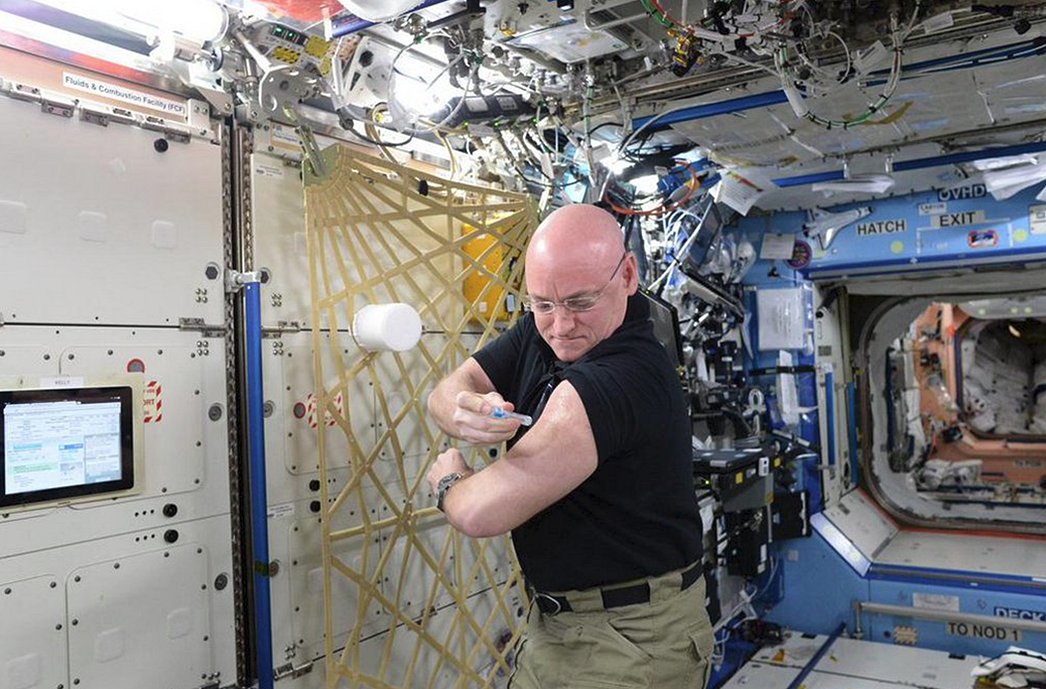

“Astronauts must do two to three hours of exercise every day just to maintain muscle mass and cardiovascular fitness. The heart loses muscle which would be extremely dangerous if they didn’t maintain it through exercise.”

Tight, elastic body suits or ‘penguin suits’, developed by the Soviet space program, attempt to mimic the effects of gravity on muscles by providing a deep compression force on the skin, muscle, and bone – meaning they have to work harder to perform normal movements. But they’re far from perfect, says Dr Jurblum.

However, like many innovations space technology generates, these space suits are now used in the rehabilitation of cerebral palsy, as a loading and training device that provides muscle resistance.

A common hazard on the ISS are the fine specks that float around the cabin, often lodging in the eyes’ of astronauts and causing abrasions. But again, it’s the issue of the lack of gravity and the movement of fluids that can cause the most serious issues.

Sciences & Technology

To infinity and beyond

“Most end up wearing glasses in space and when they come back, some even have permanent changes to their vision,” says Dr Jurblum.

This deterioration is caused by the fluid shift to the head building up in the skull where it bulges into the back of the eyeball and changes the shape of the lens.

“This bulging seems to cause the irreversible vision problems we’re trying to understand and manage.”

Currently, NASA is researching the issue which is one of several hurdles on the list before a manned missions to Mars is ready to go.

If you catch a cold on Earth, you stay home and it’s no big deal. Space is another story.

You’re living a densely packed, confined space - breathing recirculated air, touching common surfaces over and over again, with a lot less opportunity to wash.

The human immune system doesn’t work as well in space, so mission members are isolated for a few weeks before lift-off to guard against illness.

Apollo 7’s Wally Schirra came down with a cold in the middle of his mission, which was then passed onto several other astronauts. According to reports from the time, the men were cranky and miserable - even breaking mission rules when they refused to wear their helmets during re-entry, so they could blow their noses.

“We’re not sure why, but it seems that bacteria are more dangerous in space. On top of that, if you sneeze in space, all the droplets come straight out and keep going. If someone has a flu, everyone is going to get it and there are limited medical facilities and a very long way to the nearest hospital.”

Luckily, there have not yet been any major medical emergencies in space, but astronauts are trained to deal with them, says Dr Jurblum.

For instance, ISS astronauts have developed a way to perform CPR in zero gravity by bracing their legs on the ceiling while pushing down on the patient on the floor below.

While a rescue from the ISS can be performed within a day, the people who go Mars will be an eight-month journey away, and they need to be prepared to manage on their own, Dr Jurblum says.

And that requires practice. Here on Earth, there are experiments around the world that simulate some of the conditions human beings could experience during a future mission to Mars.

These are called Mars Analogues and it’s these experiments that are allowing researchers to work on solutions to situations like what to do if a team member breaks their leg while outside the base.

“How do you lift them on a stretcher, get them into an airlock, out of their suit and onto a surgical table with a doctor, a botanist and a couple of scientists to help do surgery? You may have an orthopaedic surgeon on Earth sending you information on how to do it, but there is a 20-minute time delay,” Dr Jurblum says.

Other information has been gathered from work with submarine crews, cavers, mountain climbers, and Australia’s Antarctic Division, as well as NASA’s underwater ‘space’ base Aquarius. The Mars Society Australia hopes to create its own Mars analogue in the Australian desert.

Sciences & Technology

An astrophysicist meets The Martian

But despite these health hurdles, Dr Jurblum says humans venturing to Mars isn’t a matter of if, but when. And one of the keys to this is keeping those space pioneers healthy, 54.6 million kilometres away from Earth.

“In the next 30 years we’ll see all this happening, and it will be an international effort” he says.

And, according to Dr Jurblum, Australia will play a part.

“The Australasian Society of Aerospace Medicine is trying to bring together doctors, biomedical scientists and students of all sorts from around the country in a national network to work on some of the health problems and get us to Mars”.

Banner image: NASA