Health & Medicine

Chemogenetics: A new way to understand brain function

As parts of the world emerge from lockdown, psychiatrists and neurologists warn that we need to know more about the long-lasting neurological and neuropsychiatric impacts of COVID-19

Published 4 October 2020

Most of us know of COVID-19 as a respiratory illness, accompanied by what some call a ‘parallel pandemic’ of growing mental health problems.

But as more COVID-19 patients recover, neurological and neuropsychiatric impacts are proving more common than we anticipated. While the exact figure is not yet clear, it can be as high as 84 per cent.

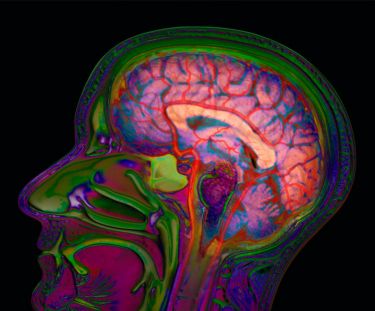

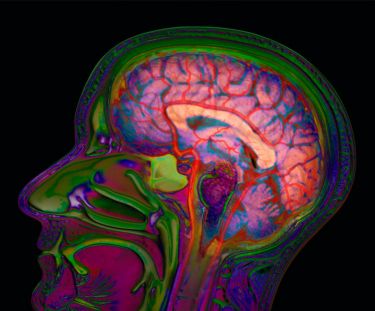

And the virus is showing up in brain scans, cerebrospinal fluid, and even semen.

In reviewing reams of evidence from case reports and other sources, Professor Christos Pantelis and Dr Mahesh Jayaram, along with a team of other medical specialists and neuroscientists, published research in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, warning that much is still unknown about the neurological, neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental effects of contracting COVID-19.

“We’ve never seen anything like this before. It’s a really complex virus,” says Dr Jayaram.

Health & Medicine

Chemogenetics: A new way to understand brain function

“Scientific papers are being published at warp speed, showing significant impact on the brain. This may be due to direct infiltration of the virus into the nervous system, but also from the effects of severe inflammation and subsequent blood clots.

“We also do not know the extent to which nervous system infection contributes to COVID’s high death rate.”

Loss of smell and taste (known as anosmia and ageusia), experienced by almost two thirds of patients, was until recently seen as an annoying but benign viral quirk.

But now, it’s seen as a harbinger of more serious impacts such as confusion, delirium and even psychosis.

This may be because the suspected pathway taken by the virus also allows it to infiltrate the brain directly via the olfactory nerve, and impact on areas that regulate emotions and memory.

The amygdala, hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex all mediate intense states of fear, anger and aggression, intensifying these responses or dampening them.

Health & Medicine

Mapping the terra incognita of our brains

The impact on the brain may also affect an infected person’s response to low oxygen levels (hypoxia) with severe lung infection leading to a lack of concern about this life-threatening state.

This has been termed ‘happy hypoxia’, however, other explanations have been suggested, including blood clots in the small vessels of the lungs leading to patients being unaware of and unperturbed by their own plummeting oxygen levels.

In some instances, this has led to sudden deaths – even in younger people.

“There are reports of some younger patients presenting as perfectly fine the night before who died alone during the night,” Professor Pantelis says.

“Psychiatric symptoms like a loss of social inhibition, apparent unconcern, or confusion can easily be overlooked or mistaken for other, non-COVID, conditions. Recognising these complex symptoms early can be life-saving” he says.

But in gathering evidence about the direct effects of the virus on the brain, the team noticed other effects.

“Our team noted that the most severe damage has been due to blood clots (thrombosis) in the brain and other organs, including the lungs and heart – secondary to the so-called cytokine (inflammatory) storm”, says Dr Jayaram.

Health & Medicine

Will COVID-19 change healthcare for stroke patients?

Another concern is what happens to the offspring of women who are infected before and during pregnancy.

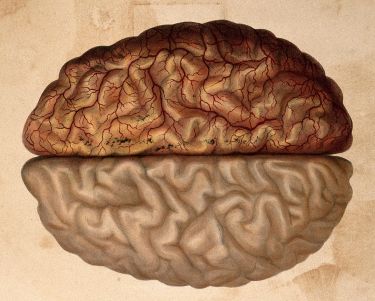

Previous research has demonstrated that viral infections play a role in neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism, epilepsy and schizophrenia that become apparent in the late teens and early adulthood.

The detection of SARS-Cov-2 virus or associated inflammation in the placenta, as well as evidence of virus in semen, suggests that researchers will need to keep an eye out for effects on subsequent development, particularly brain development.

Research on rodents has shown that ‘cytokine storms’ triggered by the mother’s immune response to COVID-19 can lead to significant neurodevelopmental changes in the course of neural development.

So far, despite isolated reports of ‘vertical transmission’ from mother to foetus via the placenta, and during labour, COVID-19 positive women are delivering healthy babies.

“The first trimester is absolutely critical to neural development,” Dr Jayaram says.

Health & Medicine

Training your brain in lockdown

“Thankfully, we’re not seeing birth defects or a specific syndrome that we saw with Zika virus. Nor are we seeing hypoxia or delays in first breath taken by babies. But it’s very early days.

“We need to establish a cohort of kids that are born during and after the COVID-19 pandemic to see what happens years and decades later, and those studies need to include children whose fathers, not just their mothers, were infected,” says Professor Anthony Hannan, Head of the Epigenetics and Neural Plasticity Laboratory at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health and one of the study authors.

“Both paternal and maternal infection could potentially affect children. This, in turn, could have major public health implications for the next generation.”

As the world starts winding back lockdowns, the two researchers warn that the jury is still out on reinfection.

Vagaries of testing aside, there are concerns that the virus might behave like herpes, another scourge of the central nervous system, lying low and flaring up at times of stress, never completely going away.

Antibodies may only confer short-term immunity, although there is some promise with emerging vaccine candidates – but we just don’t know enough about this yet.

Health & Medicine

Delving into memory to understand schizophrenia

“Repeated infection or higher dose of virus may increase mortality of healthcare workers,” says Dr Jayaram. To date, more than 3,500 Victorian healthcare workers have been infected by the virus.

The study authors are urging global collaboration to learn more about the central nervous system impacts, and their role in the high death rates from the disease.

“We are establishing a national registry to collate clinical information about unusual neurological presentations, and we aim to collaborate with other similar international consortia,” says Dr Robb Wesselingh, a neurologist at Alfred Health and Monash University, who is another of the study authors.

“There is still much to learn about COVID-19. These frontline observations will be critical for early detection and management of the disease,” says Professor Pantelis.

“Understanding the potential long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric impacts of COVID-19 – including possible intergenerational effects – will provide a clearer guide to managing viruses in the future.”

Banner: Shutterstock