Politics & Society

Truth telling at Garma

The theme for this year’s National Reconciliation Week is ‘grounded in truth, walk together with courage’, but to do this requires truth telling. And there are some initiatives and policies in 2019 taking a step in the right direction

Published 26 May 2019

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following article contains images and voices of deceased persons.

Karen Mundine, the CEO of Reconciliation Australia – a non-government, not-for-profit foundation promoting a continuing national focus on reconciliation – says that “reconciliation is ultimately about relationships and, like all effective relationships, the one between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and other Australians must be grounded in truth.

“There can be no trust without an honest, open conversation about our history.”

She went on to say that: “According to the 2018 Australian Reconciliation Barometer, 80 per cent of Australians believe it is important to undertake formal truth telling processes.”

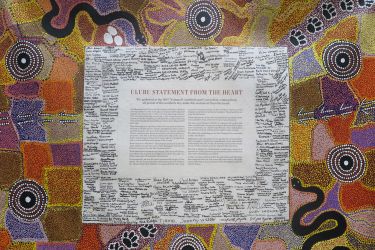

The idea of truth telling is also central to the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The statement was a call to action that included “the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution, a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations, and truth-telling about our history”.

The statement invited all Australians to “walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future”.

Politics & Society

Truth telling at Garma

But walking together means learning from each other, and while there’s still a long way to go, there are several initiatives that take us a step closer.

The first is the role our Indigenous media sector is playing in truth telling, and second, is the need for recognition that some of the things taken from us, must be returned.

In 2019, you can learn about our diversity and languages through the work of media organisations like National Indigenous Television (NITV), Indigenous Community TV (ICTV) and Indigitube, the web-based platform of First Nations Media Australia.

This year is also the International year of Indigenous languages.

In 1788, we had more than 250 languages in Australia with 800 dialect varieties. Today, there are less than 100 Indigenous languages spoken, and less than 20 languages that are still learned by the next generation of children.

But there’s now a movement to help preserve and keep our languages alive, including revitalisation programs across the country.

Arts & Culture

The many voices of the North

The strength of Indigenous creativity, resilience and resistance is also front and centre at the Festival of Remote Australian Indigenous Moving-Image, (FRAIM) run by Rita Cattoni and her brilliant team at ICTV.

The workshops attached to the festival include ten trainers from across the remote Australia, educating participants in video production skills that include the recording of traditional stories and dances; documentation of bush trips, bush craft and bush medicine; caring for country and hunting videos; as well as 2D and 3D animations of cultural stories.

This process explores the practicalities of covering traditional events in remote or difficult locations while also maintaining the cultural integrity of the finished videos.

Importantly, workshops like this provide important training for remote communities the enable them to work to keep their culture and language alive through contemporary recordings of them.

ICTV recently launched, as part of the International Year of Indigenous Languages, their inLanguage project where anyone can find audio and video content from 20 selected languages and language groups, making our languages easily available.

The project, which is sponsored by Australian Government’s Indigenous Languages and Arts program, the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education and First Languages Australia, is one of several initiatives that brings truth telling and the Indigenous stories of this country to the mainstream.

But, the preservation languages and cultural heritage also means giving materials and information taken from Aboriginal people back to them. This includes the repatriation on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander human remains and secret sacred objects.

Arts & Culture

Bringing back languages from scraps of paper

In 2014, the Advisory Committee for Indigenous Repatriation, an advisory committee to the Commonwealth, provided a report on national consultations for the National Resting Place of unprovenanced Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander human remains (Ancestral Remains) that are currently held in museums.

The collecting of Indigenous remains started after the First Fleet arrived. They were taken from burial sites, massacre sites, hospitals and morgues, in order to satisfy the trade in Ancestral remains and for studies in the theories of evolution.

It’s estimated that thousands of remains were collected and sent overseas, although exact numbers are hard to pin down. At home, a recent survey of Australian institutions estimates that there are still over one thousand Ancestral Remains that still need to be returned.

Part of any truth telling and reconciliation means owning up to the past and righting those wrongs through programs like the return of human remains and sacred objects.

The establishment of a National Resting Place is a long-standing request by Aboriginal people and has gained bi-partisan political support.

The Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples recommended that “the Australian Government consider the establishment, in Canberra, of a National Resting Place, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander remains, which could be a place of commemoration, healing and reflection”.

Politics & Society

Duty and honour at the heart of Indigenous recognition

The newly re-elected Morrison government has already supported the establishment of a National Resting Place in line with the recommendations of the Joint Select Committee. The Government has committed $A5 million to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies to undertake a scoping study and consultation as a first step.

In the words of the government, “it supports a process of truth telling as part of our nation’s journey to reconciliation. Our Government’s commitment to a National Resting Place also supports the process of truth telling”.

But to establish a National Resting Place, there needs to be a new national legislative framework for the repatriation of Ancestral Remains and secret sacred objects, similar to the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Act which was amended 2016.

This would create a co-ordinated approach, across the states and territories, regulating the return of of Ancestral Remains and secret sacred objects, as well as the relevant funding and support needed to enable genuine healing and truth telling.

As Arrernte man Shaun Angeles Penangke, who is the Artwe-kenhe (Men’s) Collection Researcher at the Strehlow Research Centre, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, says:

“The engagement and governance of elders of our Indigenous cultural heritage and ancestors within museums is a no brainer – it’s imperative to the healing of our people. Our Elders are the only people on the face of the planet who can understand and enrich the contents of such collections.

“Our lands were plundered of our ancient treasures and ancestors, and it is our right as First Nations people to have these returned. They are our ancestors and we are their direct descendants who still hold their sacred Law.”

Truth telling is essential, not just for Aboriginal people but for all Australians, as part of the reconciliation process.

But true reconciliation means that Australia and Australians must work to protect and preserve our people’s deep time history of this wonderful continent.

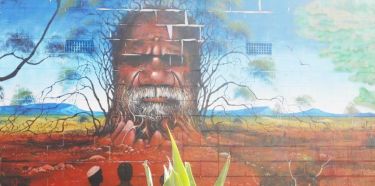

Banner: Paul Burston/University of Melbourne