Health & Medicine

Why is no-one talking about safe sex for the over 60s?

Research is showing that a new microsurgery procedure to regrow nerves to the penis severed during a prostatectomy can successfully restore a man’s ability to have an erection

Published 11 April 2019

Plastic surgeon Professor Chris Coombs knows whether his new surgical technique has worked as soon as a patient walks into his office.

“They’re confident, they sit up straight and they’re smiling. They think it’s grouse.”

What they are smiling about is being able to get an erection again, sometimes after as much as a decade of impotency.

Professor Coombs, a microsurgeon at the Royal Children’s Hospital and the Department of Surgery at the University of Melbourne, and urologist Mr David Dangerfield, are at the forefront of establishing a new microsurgery procedure to restore potency to men who have had the erectile nerve connections to their penis damaged after having their prostate removed as a result of cancer.

In 70 per cent of prostatectomies the patient will permanently lose the ability to have an erection, even when “nerve sparing” surgery is used in which surgeons carefully peel erectile nerves away from the prostate.

Health & Medicine

Why is no-one talking about safe sex for the over 60s?

Men with the resulting erectile dysfunction are unable to have penetrative sex without the assistance of penile injections (that can be painful), a surgically-inserted prosthetic pump or external vacuum devices.

Some 8,500 men with prostate cancer undergo a radical prostatectomy every year in Australia. In the US, more than 90,000 men a year undergo the procedure. And the great majority of these men will be left with erectile dysfunction.

“It is a huge global health problem that just isn’t talked about,” says University of Melbourne National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) research fellow Dr Jeanette Reece in the Melbourne School of Population Health. “Erectile dysfunction can seriously undermine a man’s quality of life.”

Because the erectile nerves that pass around the prostate en route to the penis are a web of tiny nerve fibres, it’s almost impossible for surgeons to repair them in the usual way – taking a nerve graft and connecting it end-to-end to the severed nerves.

But a small-scale University of Melbourne study has found that Professor Coombs’ “end-to-side” nerve grafting is successfully restoring erectile function in just over 70 per cent of cases.

The procedure involves connecting a nerve graft to the side of the femoral nerve in the thigh, enabling part of the femoral nerve to branch off and grow into the penis where it can restore the nerve connections.

Health & Medicine

How challenging masculine stereotypes is good for men

Published in European Urology, the study of 17 patients found that 12 were able to again experience an erection sufficient for penetrative sex, and of these, seven didn’t need Viagra-like drugs to assist their erection. Of the 12 men, two had suffered erectile dysfunction for over ten years. The average age of participants was 64 with ages ranging from 49 to 69.

In the study, lead author Dr Reece independently assessed erectile performance and sexual quality of life using questionnaires filled out both before the procedure and at three to six monthly intervals up to a period of three years after the surgery.

The results compare with a Brazilian study last year that found that an earlier end-to-side femoral nerve technique, first pioneered by Brazilian surgeon Professor Fausto Viterbo, had a 60 per cent success rate across ten patients.

The key difference with the Australian technique, developed by Professor Coombs and Mr Dangerfield, is that they make a slight incision into the nerve fibres of an area of the femoral nerve to increase nerve fibre growth into the nerve graft.

“When you make a slight incision in the nerve fibres you can promote greater growth from the nerve endings,” says Professor Coombs.

Health & Medicine

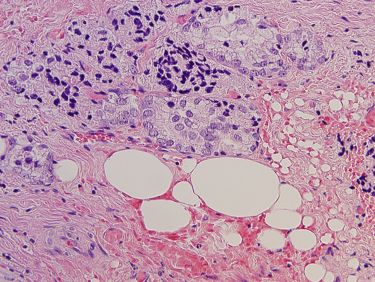

Prostate cancer: Starving out the enemy

The idea behind the surgery is to restore the supply of the chemical that the erectile nerves in the penis transmit to trigger an erection. The same chemical is transmitted by the femoral nerve to help us walk.

The trick then is to link the two together. To do this Professor Coombs takes a 30 centimetre section of the sural nerve in the lower leg to use as a graft. The only side effect of taking this graft from the sural nerve is the loss of some sensation on the outside of the foot.

Once harvested, the nerve fibres inside the sural nerve graft quickly die. That leaves just the outer casing, like an electrical cord with the copper wire missing.

With just an incision in the hip and in the groin, Professor Coombs sews this empty nerve ‘tubing’ onto the side of the femoral nerve, and threads the other end down to the base of the penis. It is then left for the femoral nerve fibres to grow through this empty nerve graft down to the penis where the fibres then branch out to connect with the erectile tissue of the penis.

This is all done at four-and-a-half times magnification using nylon thread that is half the thickness of a human hair.

“In a sense, we are putting in an electrical extension cord but without the copper inside. We then wait for the femoral nerve fibres to grow inside the extension cord until they eventually reach the penis,” says Professor Coombs.

Health & Medicine

Heart plumbing: The pipes matter

The nerve fibre in the femoral nerve grows down the graft at around one millimetre a day and it can take around 12 months for the connection to be restored.

Professor Coombs first came across the technique at a conference presentation given by Professor Viterbo, and he later travelled to Brazil to learn how to do it.

Slightly cutting a nerve to promote growth is common plastic surgery practice, and it seemed to Professor Coombs an obvious enhancement to make. For the example, the same incision technique is used in restoring and promoting the nerve connections to the face in cases of facial palsy.

Professor Coombs says the incision on the femoral nerve fibre has had no impact on patients other than occasional transitory weakness in the quadricep muscles.

“Patients aren’t reporting any residual weakness and that’s because there is redundancy built into our nervous systems – there are plenty of nerve fibres there,” says Professor Coombs.

Dr Reece, who is based at the Centre for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, says the research focus is now on increasing the size of the study.

“We’ve done a small-scale study, which is an important first step in evaluating the efficacy of this procedure,” says Dr Reece.

Health & Medicine

Training for recovery before major surgery

“We now need larger studies to determine precise rates of erectile function recovery which will, in turn, provide further evidence to support recommending nerve grafting as a first-line treatment option for erectile dysfunction.”

So far, Professor Coombs and Mr Dangerfield have carried out over 40 operations using this procedure, and ideally Dr Reece would want a new study to take in at least 100 patients.

A larger study could also shed light on why the procedure isn’t successful on all patients – perhaps identifying those patient that, for whatever reason, aren’t able to benefit.

“We need to understand why it is that 30 per cent of patients aren’t experiencing the full benefit so that we can make sure we are operating only on people who we can help,” says Professor Coombs.

In addition, Dr Reece wants to expand the quality of life assessments she carried out on patients in the study beyond sex to cover improvements in general quality of life once men recover their erectile function.

Sciences & Technology

‘Safe’ herbicide in Australian water affects male fertility

“This is a particularly important factor as 95 per cent of men who undergo a prostatectomy because of cancer go on to live for at least another ten years.”

Professor Coombs says a validated procedure that can restore erectile function in most men following a prostatectomy could be an important signal in encouraging men with localised prostate cancer to go ahead and have the prostate removed.

Aprevious studysuggests that some men may think twice before having a life-saving prostatectomy given the high risk of erectile dysfunction.

“This procedure could influence the decision of men with localised prostate cancer to go ahead with a prostatectomy if they knew there was a minimally invasive procedure available that could potentially restore their ability to have an erection.”

Professor Coombs and Dr Dangerfield operate private practices where this procedure is offered.

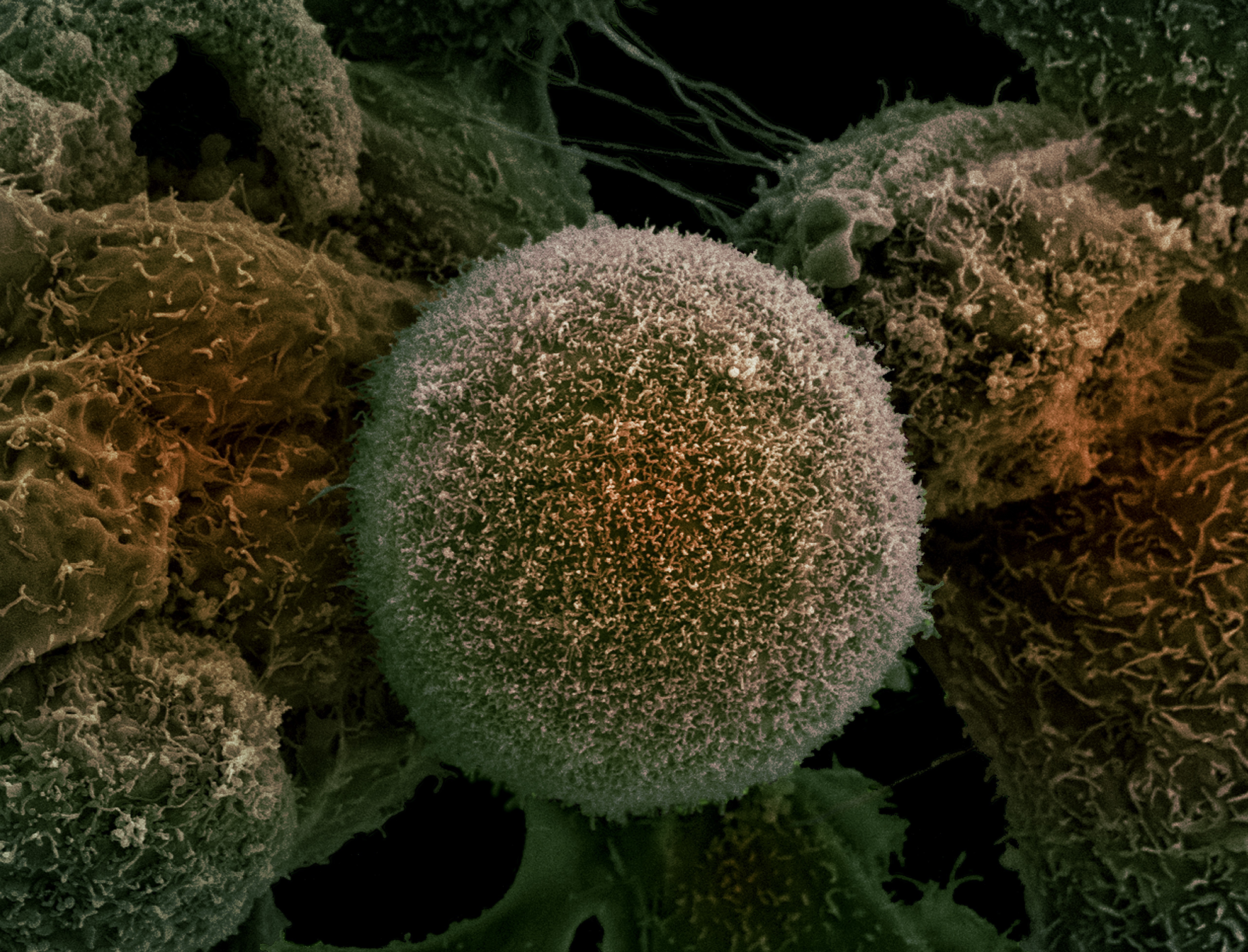

Banner image: Getty Images